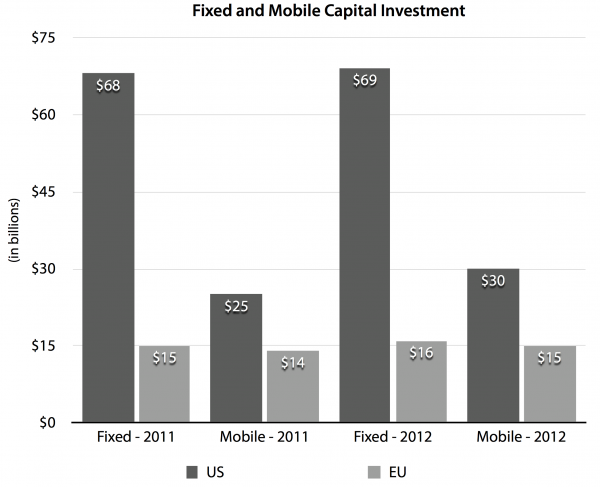

In its effort to regulate the Internet, the Federal Communications Commission is swimming upstream against a flood of evidence. The latest data comes from Fred Campbell and the Internet Innovation Alliance, showing the startling disparities between the mostly unregulated and booming U.S. broadband market, and the more heavily regulated and far less innovative European market. In November, we showed this gap using the measure of Internet traffic. Here, Campbell compares levels of investment and competitive choice (see chart below). The bottom line is that the U.S. invests around four times as much in its wired broadband networks and about twice as much in wireless. It’s not even close. Why would the U.S. want to drop America’s hugely successful model in favor of “President Obama’s plan to regulate the Internet,” which is even more restrictive and intrusive than Europe’s?

Federal Court strikes down FCC “net neutrality” order

Today, the D.C. Federal Appeals Court struck down the FCC’s “net neutrality” regulations, arguing the agency cannot regulate the Internet as a “common carrier” (that is, the way we used to regulate telephones). Here, from a pre-briefing I and several AEI colleagues did for reporters yesterday, is a summary of my statement:

A Decade Later, Net Neutrality Goes To Court

Today the D.C. Federal Appeals Court hears Verizon’s challenge to the Federal Communications Commission’s “Open Internet Order” — better known as “net neutrality.”

Hard to believe, but we’ve been arguing over net neutrality for a decade. I just pulled up some testimony George Gilder and I prepared for a Senate Commerce Committee hearing in April 2004. In it, we asserted that a newish “horizontal layers” regulatory proposal, then circulating among comm-law policy wonks, would become the next big tech policy battlefield. Horizontal layers became net neutrality, the Bush FCC adopted the non-binding Four Principles of an open Internet in 2005, the Obama FCC pushed through actual regulations in 2010, and now today’s court challenge, which argues that the FCC has no authority to regulate the Internet and that, in fact, Congress told the FCC not to regulate the Internet.

Over the years we’ve followed the debate, and often weighed in. Here’s a sampling of our articles, reports, reply comments, and even some doggerel:

- “CBS-Time Warner Cable Spat Shows (Once Again) Why ‘Net Neutrality’ Won’t Work” – by Bret Swanson – August 9, 2013

- “Verizon, ESPN, and the Future of Broadband” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – June 4, 2013

- “The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now” – by Bret Swanson – RealClearMarkets – December 6, 2010

- “Reply Comments to the FCC’s Open Internet Further Inquiry” – by Bret Swanson – November 4, 2010

- “Net Neutrality, Investment, and Jobs: Assessing the Potential Impact on the Broadband Ecosystem” – by Charles M. Davidson and Bret T. Swanson, Advanced Communications Law and Policy Institute, New York Law School, June 16, 2010

- “The Regulatory Threat to Web Video” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – May 17, 2010

- “Reply Comments in the FCC Matter of ‘Preserving the Open Internet’” – by Bret Swanson – April 26, 2010

- “What Would Net Neutrality Mean for U.S. Jobs?” – by Bret Swanson – February 5, 2010

- “Net Neutrality’s Impact on Internet Innovation” – prepared for the New York City Council – by Bret Swanson – November 20, 2009

- “Google and the Problem With ‘Net Neutrality’” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, October 5, 2009

- “Leviathan Spam” – by Bret Swanson – A whimsical take on “Net Neutrality” – September 23, 2009

- “Unleashing the ‘Exaflood’” – by Bret Swanson and George Gilder, The Wall Street Journal, February 22, 2008

- “The Coming Exaflood” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2007

- “Let There Be Bandwidth” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2006

- “Testimony For Telecommunications Policy: A Look Ahead” – testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee – by George Gilder – April 28, 2004

— Bret Swanson

Akamai CEO Exposes FCC’s Confused “Paid Priority” Prohibition

In the wake of the FCC’s net neutrality Order, published on December 23, several of us have focused on the Commission’s confused and contradictory treatment of “paid prioritization.” In the Order, the FCC explicitly permits some forms of paid priority on the Internet but strongly discourages other forms.

From the beginning — that is, since the advent of the net neutrality concept early last decade — I argued that a strict neutrality regime would have outlawed, among other important technologies, CDNs, which prioritized traffic and made (make!) the Web video revolution possible.

So I took particular notice of this new interview (sub. required) with Akamai CEO Paul Sagan in the February 2011 issue of MIT’s Technology Review:

TR: You’re making copies of videos and other Web content and distributing them from strategic points, on the fly.

Paul Sagan: Or routes that are picked on the fly, to route around problematic conditions in real time. You could use Boston [as an analogy]. How do you want to cross the Charles to, say, go to Fenway from Cambridge? There are a lot of bridges you can take. The Internet protocol, though, would probably always tell you to take the Mass. Ave. bridge, or the BU Bridge, which is under construction right now and is the wrong answer. But it would just keep trying. The Internet can’t ever figure that out — it doesn’t. And we do.

There it is. Akamai and other content delivery networks (CDNs), including Google, which has built its own CDN-like network, “route around” “the Internet,” which “can’t ever figure . . . out” the fastest path needed for robust packet delivery. And they do so for a price. In other words: paid priority. Content companies, edge innovators, basement bloggers, and poor non-profits who don’t pay don’t get the advantages of CDN fast lanes. (more…)

The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now

See my analysis of the FCC’s new “net neutrality” policy at RealClearMarkets:

Despite the Federal Communications Commission’s “net neutrality” announcement this week, the American Internet economy is likely to survive and thrive. That’s because the new proposal offered by FCC chairman Julius Genachowski is lacking almost all the worst ideas considered over the last few years. No one has warned more persistently than I against the dangers of over-regulating the Internet in the name of “net neutrality.”

In a better world, policy makers would heed my friend Andy Kessler’s advice to shutter the FCC. But back on earth this new compromise should, for the near-term at least, cap Washington’s mischief in the digital realm.

. . .

The Level 3-Comcast clash showed what many of us have said all along: “net neutrality” was a purposely ill-defined catch-all for any grievance in the digital realm. No more. With the FCC offering some definition, however imperfect, businesses will now mostly have to slug it out in a dynamic and tumultuous technology arena, instead of running to the press and politicians.

Caveats. Already!

If it’s true, as Nick Schulz notes, that FCC Commissioner Copps and others really think Chairman Genachowski’s proposal today “is the beginning . . . not the end,” then all bets are off. The whole point is to relieve the overhanging regulatory threat so we can all move forward. More — much more, I suspect — to come . . . .

FCC Proposal Not Terrible. Internet Likely to Survive and Thrive.

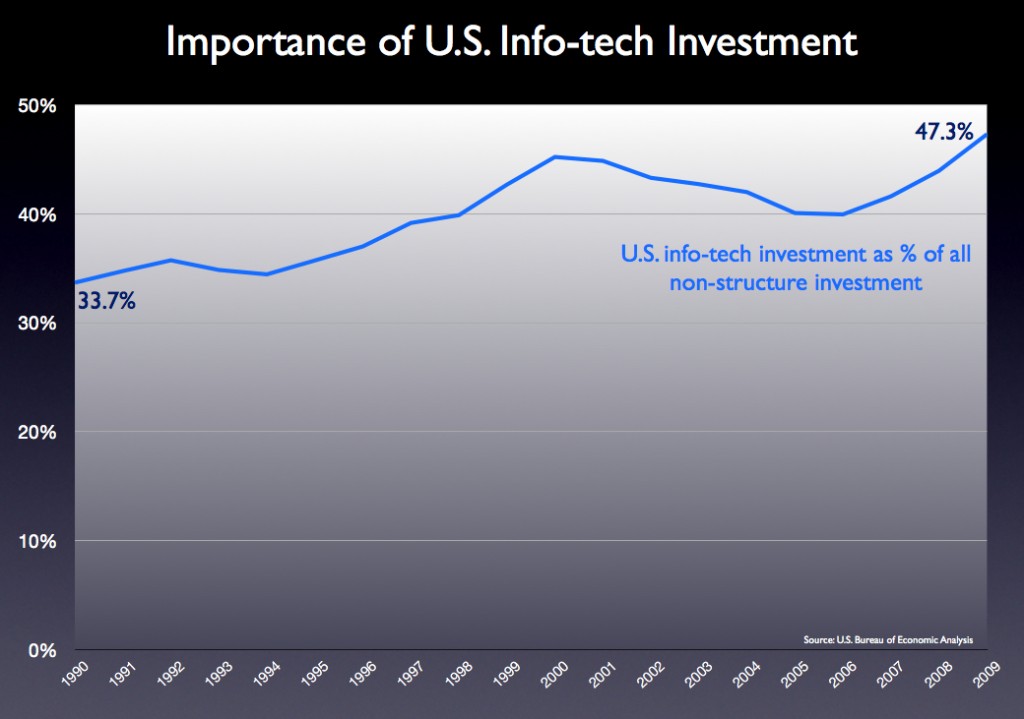

The FCC appears to have taken the worst proposals for regulating the Internet off the table. This is good news for an already healthy sector. And given info-tech’s huge share of U.S. investment, it’s good news for the American economy as a whole, which needs all the help it can get.

In a speech this morning, FCC chair Julius Genachowski outlined a proposal he hopes the other commissioners will approve at their December 21 meeting. The proposal, which comes more than a year after the FCC issued its Notice of Proposed Rule Making into “Preserving the Open Internet,” appears mostly to codify the “Four Principles” that were agreed to by all parties five years ago. Namely:

- No blocking of lawful data, websites, applications, services, or attached devices.

- Transparency. Consumers should know what the services and policies of their providers are, and what they mean.

- A prohibition of “unreasonable discrimination,” which essentially means service providers must offer their products at similar rates and terms to similarly situated customers.

- Importantly, broadband providers can manage their networks and use new technologies to provide fast, robust services. Also, there appears to be even more flexibility for wireless networks, though we don’t yet know the details.

(All the broad-brush concepts outlined today will need closer scrutiny when detailed language is unveiled, and as with every government regulation, implementation and enforcement can always yield unpredictable results. One also must worry about precedent and a new platform for future regulation. Even if today’s proposal isn’t too harmful, does the new framework open a regulatory can of worms?)

So, what appears to be off the table? Most of the worst proposals that have been flying around over the last year, like . . .

- Reclassification of broadband as an old “telecom service” under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, which could have pierced the no-government seal on the Internet in a very damaging way, unleashing all kinds of complex and antiquated rules on the modern Net.

- Price controls.

- Rigid nondiscrimination rules that would have barred important network technologies and business models.

- Bans of quality-of-service technologies and techniques (QoS), tiered pricing, or voluntary relationships between ISPs and content/application/service (CAS) providers.

- Open access mandates, requiring networks to share their assets.

Many of us have long questioned whether formal government action in this arena is necessary. The Internet ecosystem is healthy. It’s growing and generating an almost dizzying array of new products and services on diverse networks and devices. Communications networks are more open than ever. Facebook on your BlackBerry. Netflix on your iPad. Twitter on your TV. The oft-cited world broadband comparisons, which say the U.S. ranks 15h, or even 26th, are misleading. Those reports mostly measure household size, not broadband health. Using new data from Cisco, we estimate the U.S. generates and consumes more network traffic per user and per capita than any nation but South Korea. (Canada and the U.S. are about equal.) American Internet use is twice that of many nations we are told far outpace the U.S. in broadband. Heavy-handed regulation would have severely depressed investment and innovation in a vibrant industry. All for nothing.

Lots of smart lawyers doubt the FCC has the authority to issue even the relatively modest rules it outlined today. They’re probably right, and the question will no doubt be litigated (yet again), if Congress does not act first. But with Congress now divided politically, the case remains that Mr. Genachowski’s proposal is likely the near-term ceiling on regulation. Policy might get better than today’s proposal, but it’s not likely to get any worse. From what I see today, that’s a win for the Internet, and for the U.S. economy.

— Bret Swanson

The End of Net Neutrality?

In what may be the final round of comments in the Federal Communications Commission’s Net Neutrality inquiry, I offered some closing thoughts, including:

- Does the U.S. really rank 15th — or even 26th — in the world in broadband? No.

- The U.S. generates and consumes substantially more IP traffic per Internet user and per capita than any other region of the world.

- Among individual nations, only South Korea generates significantly more IP traffic than the U.S. (Canada and the U.S. are equal.)

- U.S. wired and wireless broadband networks are among the world’s most advanced, and the U.S. Internet ecosystem is healthy and vibrant.

- Latency is increasingly important, as demonstrated by a young company called Spread Networks, which built a new optical fiber route from Chicago to New York to shave mere milliseconds off the existing fastest network offerings. This example shows the importance — and legitimacy — of “paid prioritization.”

- As we wrote: “One way to achieve better service is to deploy more capacity on certain links. But capacity is not always the problem. As Spread shows, another way to achieve better service is to build an entirely new 750-mile fiber route through mountains to minimize laser light delay. Or we might deploy a network of server caches that store non-realtime data closer to the end points of networks, as many Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) have done. But when we can’t build a new fiber route or store data — say, when we need to get real-time packets from point to pointover the existing network — yet another option might be to route packets more efficiently with sophisticated QoS technologies.”

- Exempting “wireless” from any Net Neutrality rules is necessary but not sufficient to protect robust service and innovation in the wireless arena.

- “The number of Wi-Fi and femtocell nodes will only continue to grow. It is important that they do, so that we might offload a substantial portion of traffic from our mobile cell sites and thus improve service for users in mobile environments. We will expect our wireless devices to achieve nearly the robustness and capacity of our wired devices. But for this to happen, our wireless and wired networks will often have to be integrated and optimized. Wireline backhaul — whether from the cell site or via a residential or office broadband connection — may require special prioritization to offset the inherent deficiencies of wireless. Already, wireline broadband companies are prioritizing femtocell traffic, and such practices will only grow. If such wireline prioritization is restricted, crucial new wireless connectivity and services could falter or slow.”

- The same goes for “specialized services,” which some suggest be exempted from new Net Neutrality regulations. Again, necessary but not sufficient.

- “Regulating the ‘basic’ Internet but not ‘specialized’ services will surely push most of the network and application innovation and investment into the unregulated sphere. A ‘specialized’ exemption, although far preferable to a Net Neutrality world without such an exemption, would tend to incentivize both CAS providers and ISPs service providers to target the ‘specialized’ category and thus shrink the scope of the ‘open Internet.’ In fact, although specialized services should and will exist, they often will interact with or be based on the ‘basic’ Internet. Finding demarcation lines will be difficult if not impossible. In a world of vast overlap, convergence, integration, and modularity, attempting to decide what is and is not ‘the Internet’ is probably futile and counterproductive. The very genius of the Internet is its ability to connect to, absorb, accommodate, and spawn new networks, applications and services. In a great compliment to its virtues, the definition of the Internet is constantly changing.”

The Regulatory Threat to Web Video

See our commentary at Forbes.com, responding to Revision3 CEO Jim Louderback’s calls for Internet regulation.

What we have here is “mission creep.” First, Net Neutrality was about an “open Internet” where no websites were blocked or degraded. But as soon as the whole industry agreed to these perfectly reasonable Open Web principles, Net Neutrality became an exercise in micromanagement of network technologies and broadband business plans. Now, Louderback wants to go even further and regulate prices. But there’s still more! He also wants to regulate the products that broadband providers can offer.

“In the Matter of Preserving the Open Internet”

Here were my comments in the FCC’s Notice of Proposed Rule Making on “Preserving the Open Internet” — better known as “Net Neutrality”:

A Net Neutrality regime will not make the Internet more “open.” The Internet is already very open. More people create and access more content and applications than ever before. And with the existing Four Principles in place, the Internet will remain open. In fact, a Net Neutrality regime could close off large portions of the Internet for many consumers. By intruding in technical infrastructure decisions and discouraging investment, Net Neutrality could decrease network capacity, connectivity, and robustness; it could increase prices; it could slow the cycle of innovation; and thus shut the window to the Web on millions of consumers. Net Neutrality is not about openness. It is far more accurate to say it is about closing off experimentation, innovation, and opportunity.

A Victory For the Free Web

After yesterday’s federal court ruling against the FCC’s overreaching net neutrality regulations, which we have dedicated considerable time and effort combatting for the last seven years, Holman Jenkins says it well:

Hooray. We live in a nation of laws and elected leaders, not a nation of unelected leaders making up rules for the rest of us as they go along, whether in response to besieging lobbyists or the latest bandwagon circling the block hauled by Washington’s permanent “public interest” community.

This was the reassuring message yesterday from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals aimed at the Federal Communications Commission. Bottom line: The FCC can abandon its ideological pursuit of the “net neutrality” bogeyman, and get on with making the world safe for the iPad.

The court ruled in considerable detail that there’s no statutory basis for the FCC’s ambition to annex the Internet, which has grown and thrived under nobody’s control.

. . .

So rather than focusing on new excuses to mess with network providers, the FCC should tackle two duties unambiguously before it: Figure out how to liberate the nation’s wireless spectrum (over which it has clear statutory authority) to flow to more market-oriented uses, whether broadband or broadcast, while also making sure taxpayers get adequately paid as the current system of licensed TV and radio spectrum inevitably evolves into something else.

Second: Under its media ownership hat, admit that such regulation, which inhibits the merger of TV stations with each other and with newspapers, is disastrously hindering our nation’s news-reporting resources and brands from reshaping themselves to meet the opportunities and challenges of the digital age. (Willy nilly, this would also help solve the spectrum problem as broadcasters voluntarily redeployed theirs to more profitable uses.)

Washington liabilities vs. innovative assets

Our new article at RealClearMarkets:

As Washington and the states pile up mountainous liabilities — $3 trillion for unfunded state pensions, $10 trillion in new federal deficits through 2019, and $38 trillion (or is it $50 trillion?) in unfunded Medicare promises — the U.S. needs once again to call on its chief strategic asset: radical innovation.

One laboratory of growth will continue to be the Internet. The U.S. began the 2000’s with fewer than five million residential broadband lines and zero mobile broadband. We begin the new decade with 71 million residential lines and 300 million portable and mobile broadband devices. In all, consumer bandwidth grew almost 15,000%.

Even a thriving Internet, however, cannot escape Washington’s eager eye. As the Federal Communications Commission contemplates new “network neutrality” regulation and even a return to “Title II” telephone regulation, we have to wonder where growth will come from in the 2010’s . . . .

Did the FCC get the White House jobs memo?

That’s the question I ask in this Huffington Post article today.

20 Good Questions

Wyoming wireless operator Brett Glass has 20 questions for the FCC on Net Neutrality. Some examples:

1. I operate a public Internet kiosk which, to protect its security and integrity, has no way for the user to insert or connect storage devices. The FCC’s policy statement says that a provider of Internet service must allow users to run applications of their choice, which presumably includes uploading and downloading. Will I be penalized if I do not allow file uploads and downloads on that machine?

4. I operate a wireless hotspot in my coffeehouse. I block P2P traffic to prevent one user from ruining the experience for my other customers. Do the FCC rules say that I must stop doing this?

6. I am a cellular carrier who offers Internet services to users of cell phones. Due to spectrum limitations, multimedia streaming by more than a few users would consume all of the bandwidth we have available not only for data but also for voice calls. May we restrict these protocols to avoid running out of bandwidth and to avoid disruption to telephone calls (some of which may be E911 calls or other urgent traffic)?

7. I am a wireless ISP operating on unlicensed spectrum. Because the bands are crowded and spectrum is scarce, I must limit each user’s bandwidth and duty cycle. Rather than imposing hard limits or overage charges, I would like to set an implicit limit by prohibiting P2P, with full disclosure that I am doing so. Is this permitted under the FCC’s rules?

14. I am an ISP that accelerates users’ Web browsing by rerouting requests for Web pages to a Web cache (a device which speeds up Web browsing, conceived by the same people who developed the World Wide Web) and then to special Internet connections which are asymmetrical (that is, they have more downstream bandwidth than upstream bandwidth). The result is faster and more economical Web browsing for our users. Will the FCC say that our network “discriminates” by handling Web traffic in this special way to improve users’ experience?

15. We are an ISP that improves the quality of VoIP by prioritizing VoIP packets and sending them through a different Internet connection than other traffic. This technique prevents users from experiencing problems with their telephone conversations and ensures that emergency calls will get through. Is this a violation of the FCC’s rules?

18. We’re an ISP that serves several large law offices as well as other customers. We are thinking of renting a direct “fast pipe” to a legal research database to shorten the attorneys’ response times when they search the database. Would accelerating just this traffic for the benefit of these customers be considered “discrimination?”

19. We’re a wireless ISP. Most of our customers are connected to us using “point-to-multipoint” radios; that is, the customers’ connection share a single antenna at our end. However, some high volume customers ask to buy dedicated point-to-point connections to get better performance. Do these connections, which are engineered by virtually all wireless ISPs for high bandwidth customers, run afoul of the FCC’s rules against “discrimination?”

Media Disruptions

Just two more New York Times articles that point out what’s obvious around here: the Internet’s dramatic and unpredictable disruption of the whole “media” space. Isn’t Washington’s assumption that it can sort all this out and impose particular business models on the media space through prescriptive Net Neutrality regulation, a case of supreme hubris?

Commone Sense of Amazonian Proportions

Amazon’s Paul Misener gets all reasonable in his comments on the FCC’s proposed net neutrality rules:

With this win-win-win goal in mind, and consistent with the principle of maintaining an open Internet, Amazon respectfully suggests that the FCC’s proposed rules be extended to allow broadband Internet access service providers to favor some content so long as no harm is done to other content.

Importantly, we note that the Internet has long been interconnected with private networks and edge caches that enhance the performance of some Internet content in comparison with other Internet content, and that these performance improvements are paid for by some but not all providers of content. The reason why these arrangements are acceptable from a public policy perspective is simple: the performance of other content is not disfavored, i.e., other content is not harmed.

Reading 15,000 documents so you don’t have to

For those of you not wishing to sift through 15,000 comments submitted to the FCC for its Net Neutrality proposed rule making, let me recommend what — so far — is the best technical filing I’ve read. It comes from Richard Bennett and Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology Innovation Foundation.

Also very useful is a new post by George Ou on content delivery and paid peering, with important policy implications.

These are among the least discussed — but most important — items in the whole Net Neutrality debate.

Separately, from the FCC’s “Open Internet” meeting at MIT last week, see summaries of each panelist’s remarks: Opening Presentations, Panel 1, Panel 2.

Collective vs. Creative: The Yin and Yang of Innovation

Later this week the FCC will accept the first round of comments in its “Open Internet” rule making, commonly known as Net Neutrality. Never mind that the Internet is already open and it was never strictly neutral. Openness and neutrality are two appealing buzzwords that serve as the basis for potentially far reaching new regulation of our most dynamic economic and cultural sector – the Internet.

I’ll comment on Net Neutrality from several angles over the coming days. But a terrific essay by Berkeley’s Jaron Lanier impelled me to begin by summarizing some of the big meta-arguments that have been swirling the last few years and which now broadly define the opposing sides in the Net Neutrality debate. After surveying these broad categories, I’ll get into the weeds on technology, business, and policy.

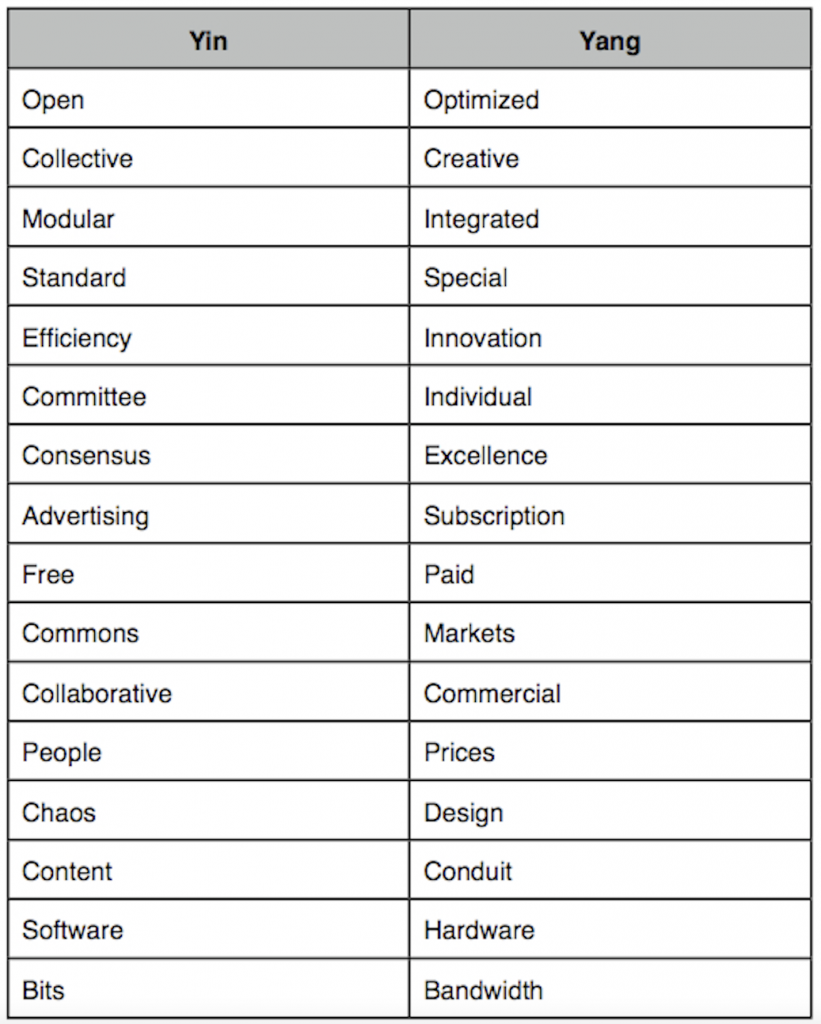

The thrust behind Net Neutrality is a view that the Internet should conform to a narrow set of technology and business “ideals” – “open,” “neutral,” “non-discriminatory.” Wonderful words. Often virtuous. But these aren’t the only traits important to economic and cultural systems. In fact, Net Neutrality sets up a false dichotomy – a manufactured war – between open and closed, collaborative versus commercial, free versus paid, content versus conduit. I’ve made a long list of the supposed opposing forces. Net Neutrality favors only one side of the table below. It seeks to cement in place one model of business and technology. It is intensely focused on the left-hand column and is either oblivious or hostile to the right-hand column. It thinks the right-hand items are either bad (prices) or assumes they appear magically (bandwidth).

We skeptics of Net Neutrality, on the other hand, do not favor one side or the other. We understand that there are virtues all around. Here’s how I put it on my blog last autumn:

Suggesting we can enjoy Google’s software innovations without the network innovations of AT&T, Verizon, and hundreds of service providers and technology suppliers is like saying that once Microsoft came along we no longer needed Intel.

No, Microsoft and Intel built upon each other in a virtuous interplay. Intel’s microprocessor and memory inventions set the stage for software innovation. Bill Gates exploited Intel’s newly abundant transistors by creating radically new software that empowered average businesspeople and consumers to engage with computers. The vast new PC market, in turn, dramatically expanded Intel’s markets and volumes and thus allowed it to invest in new designs and multi-billion dollar chip factories across the globe, driving Moore’s law and with it the digital revolution in all its manifestations.

Software and hardware. Bits and bandwidth. Content and conduit. These things are complementary. And yes, like yin and yang, often in tension and flux, but ultimately interdependent.

Likewise, we need the ability to charge for products and set prices so that capital can be rationally allocated and the hundreds of billions of dollars in network investment can occur. It is thus these hard prices that yield so many of the “free” consumer surplus advantages we all enjoy on the Web. No company or industry can capture all the value of the Web. Most of it comes to us as consumers. But companies and content creators need at least the ability to pursue business models that capture some portion of this value so they can not only survive but continually reinvest in the future. With a market moving so fast, with so many network and content models so uncertain during this epochal shift in media and communications, these content and conduit companies must be allowed to define their own products and set their own prices. We need to know what works, and what doesn’t.

When the “network layers” regulatory model, as it was then known, was first proposed back in 2003-04, my colleague George Gilder and I prepared testimony for the U.S. Senate. Although the layers model was little more than an academic notion, we thought then this would become the next big battle in Internet policy. We were right. Even though the “layers” proposal was (and is!) an ill-defined concept, the model we used to analyze what Net Neutrality would mean for networks and Web business models still applies. As we wrote in April of 2004:

Layering proponents . . . make a fundamental error. They ignore ever changing trade-offs between integration and modularization that are among the most profound and strategic decisions any company in any industry makes. They disavow Harvard Business professor Clayton Christensen’s theorems that dictate when modularization, or “layering,” is advisable, and when integration is far more likely to yield success. For example, the separation of content and conduit – the notion that bandwidth providers should focus on delivering robust, high-speed connections while allowing hundreds of millions of professionals and amateurs to supply the content—is often a sound strategy. We have supported it from the beginning. But leading edge undershoot products (ones that are not yet good enough for the demands of the marketplace) like video-conferencing often require integration.

Over time, the digital and photonic technologies at the heart of the Internet lead to massive integration – of transistors, features, applications, even wavelengths of light onto fiber optic strands. This integration of computing and communications power flings creative power to the edges of the network. It shifts bottlenecks. Crystalline silicon and flawless fiber form the low-entropy substrate that carry the world’s high-entropy messages – news, opinions, new products, new services. But these feats are not automatic. They cannot be legislated or mandated. And just as innovation in the core of the network unleashes innovation at the edges, so too more content and creativity at the edge create the need for ever more capacity and capability in the core. The bottlenecks shift again. More data centers, better optical transmission and switching, new content delivery optimization, the move from cell towers to femtocell wireless architectures. There is no final state of equilibrium where one side can assume that the other is a stagnant utility, at least not in the foreseeable future.

I’ll be back with more analysis of the Net Neutrality debate, but for now I’ll let Jaron Lanier (whose book You Are Not a Gadget was published today) sum up the argument:

Here’s one problem with digital collectivism: We shouldn’t want the whole world to take on the quality of having been designed by a committee. When you have everyone collaborate on everything, you generate a dull, average outcome in all things. You don’t get innovation.

If you want to foster creativity and excellence, you have to introduce some boundaries. Teams need some privacy from one another to develop unique approaches to any kind of competition. Scientists need some time in private before publication to get their results in order. Making everything open all the time creates what I call a global mush.

There’s a dominant dogma in the online culture of the moment that collectives make the best stuff, but it hasn’t proven to be true. The most sophisticated, influential and lucrative examples of computer code—like the page-rank algorithms in the top search engines or Adobe’s Flash—always turn out to be the results of proprietary development. Indeed, the adored iPhone came out of what many regard as the most closed, tyrannically managed software-development shop on Earth.

Actually, Silicon Valley is remarkably good at not making collectivization mistakes when our own fortunes are at stake. If you suggested that, say, Google, Apple and Microsoft should be merged so that all their engineers would be aggregated into a giant wiki-like project—well you’d be laughed out of Silicon Valley so fast you wouldn’t have time to tweet about it. Same would happen if you suggested to one of the big venture-capital firms that all the start-ups they are funding should be merged into a single collective operation.

But this is exactly the kind of mistake that’s happening with some of the most influential projects in our culture, and ultimately in our economy.

New York and Net Neutrality

This morning, the Technology Committee of the New York City Council convened a large hearing on a resolution urging Congress to pass a robust Net Neutrality law. I was supposed to testify, but our narrowband transportation system prevented me from getting to New York. Here, however, is the testimony I prepared. It focuses on investment, innovation, and the impact Net Neutrality would have on both.

“Net Neutrality’s Impact on Internet Innovation” – by Bret Swanson – 11.20.09

Must Watch Web Debate

If you’re interested in Net Neutrality regulation and have some time on your hands, watch this good debate at the Web 2.0 conference. The resolution was “A Network Neutrality law is necessary,” and the two opposing sides were:

Against

- James Assey – Executive Vice President, National Cable and Telecommunications Association

- Robert Quinn – Senior Vice President-Federal Regulatory, AT&T

- Christopher Yoo – Professor of Law and Communication; Director, Center for Technology, Innovation, and Competition, UPenn Law

For

- Tim Wu – Coined the term “Network Neutrality”; Professor of Law, Columbia Law

- Brad Burnham – VC, Union Square Ventures

- Nicholas Economides – Professor of Economics, Stern School of Business, New York University.

I think the side opposing the resolution wins, hands down — no contest really — but see for yourself.