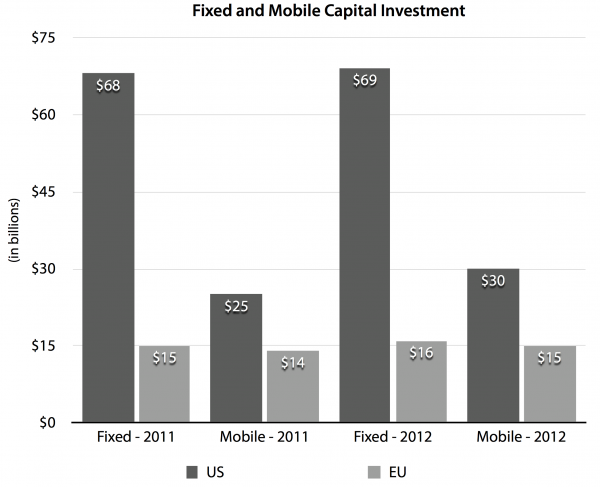

In its effort to regulate the Internet, the Federal Communications Commission is swimming upstream against a flood of evidence. The latest data comes from Fred Campbell and the Internet Innovation Alliance, showing the startling disparities between the mostly unregulated and booming U.S. broadband market, and the more heavily regulated and far less innovative European market. In November, we showed this gap using the measure of Internet traffic. Here, Campbell compares levels of investment and competitive choice (see chart below). The bottom line is that the U.S. invests around four times as much in its wired broadband networks and about twice as much in wireless. It’s not even close. Why would the U.S. want to drop America’s hugely successful model in favor of “President Obama’s plan to regulate the Internet,” which is even more restrictive and intrusive than Europe’s?

Roam, roam on the range. Will Washington’s new intrusions discourage wireless expansion?

The U.S. wireless sector has been only mildly regulated over the last decade. We’d argue this is a key reason for its success. But this presumption of mostly unfettered experimentation and dynamism may be changing.

Consider Sprint’s apparent decision to use “roaming” in Oklahoma and Kansas instead of building its own network. Now, roaming is a standard feature of mobile networks worldwide. Company A might not have as much capacity as it would like in some geography, so it pays company B, who does have capacity there, for access. Company A’s customers therefore get wider coverage, and Company B is paid for use of its network.

The problem comes with the FCC’s 2011 “digital roaming” order. Last spring three FCC commissioners decided that private mobile services — which the Communications Act says “shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier” — are a common carrier. Only D.C. lawyers smarter than you and me can figure out how to transfigure “shall not” into “may.” Anyway, the possible effect is to subject mobile data — one of the fastest growing sectors anywhere on earth — to all sorts of forced access mandates and price controls.

We warned here and here that turning competitive broadband infrastructure into a “common carrier” could discourage all players in the market from building more capacity and covering wider geographies. If company A can piggyback on company B’s network at below market rates, why would it build its own expensive network? And if company B’s network capacity is going to company A’s customers, instead of its own customers, do we think company B is likely to build yet more cell sites and purchase more spectrum?

With 37 million iPhones and 15million iPads sold last quarter, we need more spectrum, more cell towers, more capacity. This isn’t the way to get it. And what we are seeing with Sprint’s decision to roam instead of build in Oklahoma and Kansas may be the tip of this anti-investment iceberg.

Last spring when the data roaming order came down we began wondering about a possible “slow walk to a reregulated communications market.” Among other items, we cited net neutrality, possible new price controls for Special Access links to cell sites, and a host of proposed regulations affecting things like behavioral advertising and intellectual property (see, PIPA/SOPA). Since then we’ve seen the government block the AT&T-T-Mobile merger. And the FCC is now holding up its own important push for more wireless spectrum because it wants the right to micromanage who gets what spectrum and how mobile carriers can use it.

Many of these items can be thoughtfully debated. But the number of new encroachments onto the communications sector threatens to slow its growth. Many of these encroachments, moreover, are taking place outside any basic legislative authority. In the digital roaming and net neutrality cases, for example, the FCC appeared clearly to grant itself extra- if not il-legal authority. These new regulations are now being challenged in court.

We need some restraint across the board on these matters. The Internet is too important. We can’t allow a quiet, gradual reregulation of the sector to slow down our chief engine of economic growth.

— Bret Swanson

The Regulatory Threat to Web Video

See our commentary at Forbes.com, responding to Revision3 CEO Jim Louderback’s calls for Internet regulation.

What we have here is “mission creep.” First, Net Neutrality was about an “open Internet” where no websites were blocked or degraded. But as soon as the whole industry agreed to these perfectly reasonable Open Web principles, Net Neutrality became an exercise in micromanagement of network technologies and broadband business plans. Now, Louderback wants to go even further and regulate prices. But there’s still more! He also wants to regulate the products that broadband providers can offer.

Washington liabilities vs. innovative assets

Our new article at RealClearMarkets:

As Washington and the states pile up mountainous liabilities — $3 trillion for unfunded state pensions, $10 trillion in new federal deficits through 2019, and $38 trillion (or is it $50 trillion?) in unfunded Medicare promises — the U.S. needs once again to call on its chief strategic asset: radical innovation.

One laboratory of growth will continue to be the Internet. The U.S. began the 2000’s with fewer than five million residential broadband lines and zero mobile broadband. We begin the new decade with 71 million residential lines and 300 million portable and mobile broadband devices. In all, consumer bandwidth grew almost 15,000%.

Even a thriving Internet, however, cannot escape Washington’s eager eye. As the Federal Communications Commission contemplates new “network neutrality” regulation and even a return to “Title II” telephone regulation, we have to wonder where growth will come from in the 2010’s . . . .

Google and the Meddling Kingdom

Here are a few good perspectives on Google’s big announcement that it will no longer censor search results for google.cn in China, a move it says could lead to a pull-out from the Middle Kingdom.

“Google’s Move: Does it Make Sense?” by Larry Dignan

“The Google News” by James Fallows

I agree with Dignan of Znet that this move was probably less about about China and more about policy and branding in the U.S. and Europe.

UPDATE: Much more detail on the mechanics of the attack from Wired’s Threat Level blog.

Preparing to Pounce: D.C. angles for another industry

As you’ve no doubt heard, Washington D.C. is angling for a takeover of the . . . U.S. telecom industry?!

That’s right: broadband, routers, switches, data centers, software apps, Web video, mobile phones, the Internet. As if its agenda weren’t full enough, the government is preparing a dramatic centralization of authority over our healthiest, most dynamic, high-growth industry.

Two weeks ago, FCC chairman Julius Genachowski proposed new “net neutrality” regulations, which he will detail on October 22. Then on Friday, Yochai Benkler of Harvard’s Berkman Center published an FCC-commissioned report on international broadband comparisons. The voluminous survey serves up data from around the world on broadband penetration rates, speeds, and prices. But the real purpose of the report is to make a single point: foreign “open access” broadband regulation, good; American broadband competition, bad. These two tracks — “net neutrality” and “open access,” combined with a review of the U.S. wireless industry and other investigations — lead straight to an unprecedented government intrusion of America’s vibrant Internet industry.

Benkler and his team of investigators can be commended for the effort that went into what was no doubt a substantial undertaking. The report, however,

- misses all kinds of important distinctions among national broadband markets, histories, and evolutions;

- uses lots of suspect data;

- underplays caveats and ignores some important statistical problems;

- focuses too much on some metrics, not enough on others;

- completely bungles America’s own broadband policy history; and

- draws broad and overly-certain policy conclusions about a still-young, dynamic, complex Internet ecosystem.

The gaping, jaw-dropping irony of the report was its failure even to mention the chief outcome of America’s previous open-access regime: the telecom/tech crash of 2000-02. We tried this before. And it didn’t work! The Great Telecom Crash of 2000-02 was the equivalent for that industry what the Great Panic of 2008 was to the financial industry. A deeply painful and historic plunge. In the case of the Great Telecom Crash, U.S. tech and telecom companies lost some $3 trillion in market value and one million jobs. The harsh open access policies (mandated network sharing, price controls) that Benkler lauds in his new report were a main culprit. But in Benkler’s 231-page report on open access policies, there is no mention of the Great Crash. (more…)

End-to-end? Or end to innovation?

In what is sure to be a substantial contribution to both the technical and policy debates over Net Neutrality, Richard Bennett of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation has written a terrific piece of technology history and forward-looking analysis. In “Designed for Change: End-to-End Arguments, Internet Innovation, and the Net Neutrality Debate,” Bennett concludes:

Arguments for freezing the Internet into a simplistic regulatory straightjacket often have a distinctly emotional character that frequently borders on manipulation.

The Internet is a wonderful system. It represents a new standard of global cooperation and enables forms of interaction never before possible. Thanks to the Internet, societies around the world reap the benefits of access to information, opportunities for collaboration, and modes of communication that weren’t conceivable to the public a few years ago. It’s such a wonderful system that we have to strive very hard not to make it into a fetish object, imbued with magical powers and beyond the realm of dispassionate analysis, criticism, and improvement.

At the end of the day, the Internet is simply a machine. It was built the way it was largely by a series of accidents, and it could easily have evolved along completely different lines with no loss of value to the public. Instead of separating TCP from IP in the way that they did, the academics in Palo Alto who adapted the CYCLADES architecture to the ARPANET infrastructure could have taken a different tack: They could have left them combined as a single architectural unit providing different retransmission policies (a reliable TCP-like policy and an unreliable UDP-like policy) or they could have chosen a different protocol such as Watson’s Delta-t or Pouzin’s CYCLADES TS. Had the academics gone in either of these directions, we could still have a World Wide Web and all the social networks it enables, perhaps with greater resiliency.

The glue that holds the Internet together is not any particular protocol or software implementation: first and foremost, it’s the agreements between operators of Autonomous Systems to meet and share packets at Internet Exchange Centers and their willingness to work together. These agreements are slowly evolving from a blanket pact to cross boundaries with no particular regard for QoS into a richer system that may someday preserve delivery requirements on a large scale. Such agreements are entirely consistent with the structure of the IP packet, the needs of new applications, user empowerment, and “tussle.”

The Internet’s fundamental vibrancy is the sandbox created by the designers of the first datagram networks that permitted network service enhancements to be built and tested without destabilizing the network or exposing it to unnecessary hazards. We don’t fully utilize the potential of the network to rise to new challenges if we confine innovations to the sandbox instead of moving them to the parts of the network infrastructure where they can do the most good once they’re proven. The real meaning of end-to-end lies in the dynamism it bestows on the Internet by supporting innovation not just in applications but in fundamental network services. The Internet was designed for continual improvement: There is no reason not to continue down that path.

Political Noise On the Net

With an agreement between the U.S. Department of Commerce and ICANN (the nonprofit Internet Corp. for Assigned Names and Numbers, headquartered in California) expiring on September 30, global bureaucrats salivate. As I write today in Forbes, they like to criticize ICANN leadership — hoping to gain political control — but too often ignore the huge success of the private-sector-led system.

How has the world fared under the existing model?

In the 10 years of the Commerce-ICANN relationship, Web users around the globe have grown from 300 million to almost 2 billion. World Internet traffic blossomed from around 10 million gigabytes per month to almost 10billion, a near 1,000-fold leap. As the world economy grew by approximately 50%, Internet traffic grew by 100,000%. Under this decade of private sector leadership, moreover, the number of Internet users in North America grew around 150% while the number of users in the rest of the world grew almost 600%. World growth outpaced U.S. growth.

Can we really digest this historic shift? In this brief period, the portion of the globe’s population that communicates electronically will go from negligible to almost total. From a time when even the elite accessed relative spoonfuls of content, to a time in the near future when the masses will access all recorded information.

These advances do not manifest a crisis of Internet governance.

As for a real crisis? See what happens when politicians take the Internet away from the engineers who, in a necessarily cooperative fashion, make the whole thing work. Criticism of mild U.S. government oversight of ICANN is hardly reason to invite micromanagement by an additional 190 governments.