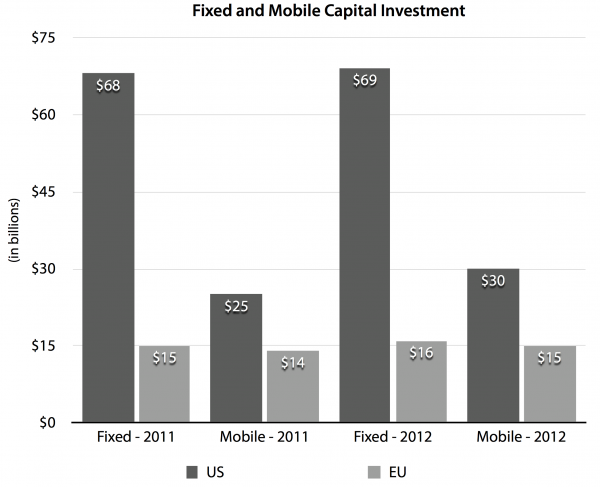

In its effort to regulate the Internet, the Federal Communications Commission is swimming upstream against a flood of evidence. The latest data comes from Fred Campbell and the Internet Innovation Alliance, showing the startling disparities between the mostly unregulated and booming U.S. broadband market, and the more heavily regulated and far less innovative European market. In November, we showed this gap using the measure of Internet traffic. Here, Campbell compares levels of investment and competitive choice (see chart below). The bottom line is that the U.S. invests around four times as much in its wired broadband networks and about twice as much in wireless. It’s not even close. Why would the U.S. want to drop America’s hugely successful model in favor of “President Obama’s plan to regulate the Internet,” which is even more restrictive and intrusive than Europe’s?

M-Lab: The Real Source of the Web Slow-Down

Last week, M-Lab, a group that monitors select Internet network links, issued a report claiming interconnection disputes caused significant declines in consumer broadband speeds in 2013 and 2014.

This was not news. Everyone knew the disputes between Netflix and Comcast/Verizon/AT&T and others affected consumer speeds. We wrote about the controversy here, here, and here, and our “How the Net Works” report offered broader context.

The M-Lab study, “ISP Interconnection and Its Impact on Consumer Internet Performance,” however, does have some good new data. Although M-Lab says it doesn’t know who was “at fault,” advocates seized on the report as evidence of broadband provider mischief at big interconnection points.

But the M-Lab data actually show just the opposite. As you can see in the three graphs below, Comcast, Time Warner, Verizon, and to a lesser extent AT&T all show sharp drops in performance in May of 2013. Then network performance of all four networks at the three monitoring points in New York, Dallas, and Los Angeles all show sudden improvements in March of 2014.

The simultaneous drops and spikes for all four suggest these firms could not have been the cause. It would have required some sort of amazingly precise coordination among the four firms. Rather, the simultaneous action suggests the cause was some outside entity or event. Dan Rayburn of StreamingMedia agrees and offers very useful commentary on the M-Lab study here.

The Need For Speed: How’s U.S. Broadband Doing?

My TechPolicyDaily colleague Roslyn Layton has begun a series comparing the European and U.S. broadband markets.

As a complement to her work, I thought I’d address a common misperception — the notion that American broadband networks are “pathetically slow.” Backers of heavier regulation of the communications market have used this line over the past several years, and for a time it achieved a sort of conventional wisdom. But is it true? I don’t think so.

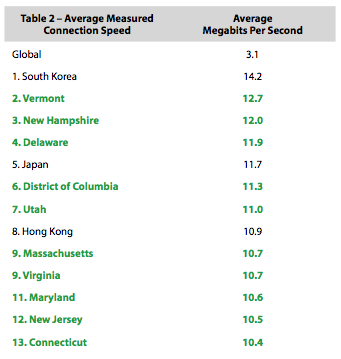

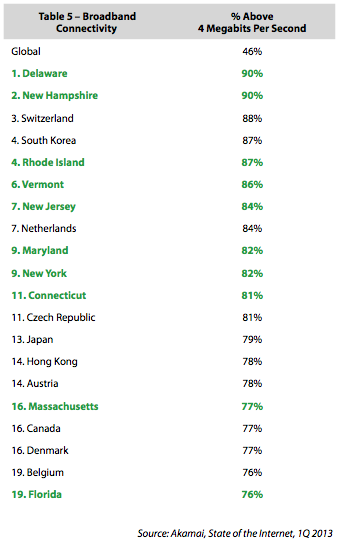

Real-time speed data collected by the Internet infrastructure firm Akamai shows U.S. broadband is the fastest of any large nation, and trails only a few tiny, densely populated countries. Akamai lists the top 10 nations in categories such as average connection speed; average peak speed; percent of connections with “fast” broadband; and percent of connections with broadband. The U.S., for example, ranks eighth among nations in average connection speed. And this is the number that is oft quoted. (This is a bit better than the no-longer-oft-used broadband penetration figures, which perennially showed the U.S. further down the list, at 15th or 26th place, for example.) Nearly all the the nations on these speed lists, however, with the exception of the U.S., are small, densely populated countries where it is far easier and more economical to build high-speed networks.

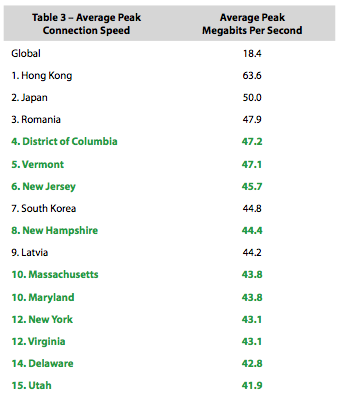

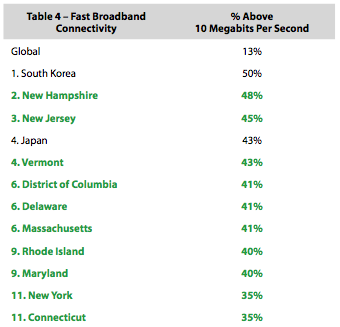

How to fix this? Well, Akamai also lists the top 10 American states in these categories. Because states are smaller, like the small nations that top the global list, they are a more appropriate basis for comparison. Last winter I combined the national and state figures and compiled a more appropriate comparative list. Using the newest data, I’ve updated the tables, which show that U.S. states (highlighted in green) dominate.

Summarizing:

- Ten of the top 13 entities for “average connection speed” are U.S. states.

- Ten of the top 15 in “average peak connection speed” are U.S. states.

- Ten of the top 12 in “percent of connections above 10 megabits per second” are U.S. states.

- Ten of the top 20 in “percent of connections above 4 megabits per second” are U.S. states.

U.S. states thus account for 40 of the top 60 slots — or two-thirds — in these measures of actual global broadband speeds.

This is not a comprehensive analysis of the entire U.S. Less populated geographic areas, where it is more expensive to build networks, don’t enjoy speeds this high. But the same is true throughout the world.

A Decade Later, Net Neutrality Goes To Court

Today the D.C. Federal Appeals Court hears Verizon’s challenge to the Federal Communications Commission’s “Open Internet Order” — better known as “net neutrality.”

Hard to believe, but we’ve been arguing over net neutrality for a decade. I just pulled up some testimony George Gilder and I prepared for a Senate Commerce Committee hearing in April 2004. In it, we asserted that a newish “horizontal layers” regulatory proposal, then circulating among comm-law policy wonks, would become the next big tech policy battlefield. Horizontal layers became net neutrality, the Bush FCC adopted the non-binding Four Principles of an open Internet in 2005, the Obama FCC pushed through actual regulations in 2010, and now today’s court challenge, which argues that the FCC has no authority to regulate the Internet and that, in fact, Congress told the FCC not to regulate the Internet.

Over the years we’ve followed the debate, and often weighed in. Here’s a sampling of our articles, reports, reply comments, and even some doggerel:

- “CBS-Time Warner Cable Spat Shows (Once Again) Why ‘Net Neutrality’ Won’t Work” – by Bret Swanson – August 9, 2013

- “Verizon, ESPN, and the Future of Broadband” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – June 4, 2013

- “The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now” – by Bret Swanson – RealClearMarkets – December 6, 2010

- “Reply Comments to the FCC’s Open Internet Further Inquiry” – by Bret Swanson – November 4, 2010

- “Net Neutrality, Investment, and Jobs: Assessing the Potential Impact on the Broadband Ecosystem” – by Charles M. Davidson and Bret T. Swanson, Advanced Communications Law and Policy Institute, New York Law School, June 16, 2010

- “The Regulatory Threat to Web Video” – by Bret Swanson – Forbes.com – May 17, 2010

- “Reply Comments in the FCC Matter of ‘Preserving the Open Internet’” – by Bret Swanson – April 26, 2010

- “What Would Net Neutrality Mean for U.S. Jobs?” – by Bret Swanson – February 5, 2010

- “Net Neutrality’s Impact on Internet Innovation” – prepared for the New York City Council – by Bret Swanson – November 20, 2009

- “Google and the Problem With ‘Net Neutrality’” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, October 5, 2009

- “Leviathan Spam” – by Bret Swanson – A whimsical take on “Net Neutrality” – September 23, 2009

- “Unleashing the ‘Exaflood’” – by Bret Swanson and George Gilder, The Wall Street Journal, February 22, 2008

- “The Coming Exaflood” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, January 20, 2007

- “Let There Be Bandwidth” – by Bret Swanson, The Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2006

- “Testimony For Telecommunications Policy: A Look Ahead” – testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee – by George Gilder – April 28, 2004

— Bret Swanson

Discussing Broadband Via Broadband

It was nice of Ball State University’s Digital Policy Institute (@DigitalPolicy) to include me last Friday in a webinar discussion on broadband policy. Joining the virtual discussion were Leslie Marx, of Duke and formerly FCC chief economist; Anna-Maria Kovacs, well-known regulatory analyst and fellow at Georgetown; and Michael Santorelli of New York Law School.

You can find a replay of the webinar here. Our broadband discussion, which begins at 1:55:48, was preceded by a good discussion of consumer online privacy, which you might also enjoy.

A Policy Path to Internet 2020

Life’s only certainty is change. Nowhere more true than with modern technologies, particularly broadband. Problem is, lots of government rules are not coming along for the ride.

Yesterday the Communications Liberty and Innovation Project (CLIP) hosted regulatory experts to discuss ways the FCC might incent more investment in digital infrastructure.

A fresh voice at the FCC is focusing the agency and the country on such a policy path of abundant wired and wireless broadband. New FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai (@AjitPaiFCC) yesterday called for the creation of an IP Transition Task Force as a way to accelerate the transition from analog networks to faster and more ubiquitous digital networks. Network providers, he said, want to know how IP services will be regulated before making major infrastructure investments. Commissioner Pai also discussed economic growth and job creation, asserting every $1 billion spent on fiber deployment creates between 15,000 and 20,000 jobs. Therefore to pave the way for robust private sector investment in the IP infrastructure, the FCC must signal a clear intention not to apply outdated 20th century regulations to these 21st century technologies.

The follow-up discussion focused on the need for a regulatory framework that will promote competition and economic growth while also maximizing consumer benefits. Jonathan Banks of US Telecom pointed out that the telecommunications industry is investing $65 billion per year, every year, in broadband infrastructure — a huge boost to current and future economic growth. Whoever occupies the White House after November should make it clear that expanding the nation’s “infostructure” with private investment dollars is a key national priority that will generate huge dividends — digital and otherwise.

FCC’s 706 Broadband Report Does Not Compute

Yesterday the Federal Communications Commission issued 181 pages of metrics demonstrating, to any fair reader, the continuing rapid rise of the U.S. broadband economy — and then concluded, naturally, that “broadband is not yet being deployed to all Americans in a reasonable and timely fashion.” A computer, being fed the data and the conclusion, would, unable to process the logical contradictions, crash.

Yesterday the Federal Communications Commission issued 181 pages of metrics demonstrating, to any fair reader, the continuing rapid rise of the U.S. broadband economy — and then concluded, naturally, that “broadband is not yet being deployed to all Americans in a reasonable and timely fashion.” A computer, being fed the data and the conclusion, would, unable to process the logical contradictions, crash.

The report is a response to section 706(b) of the 1996 Telecom Act that asks the FCC to report annually whether broadband “is being deployed . . . in a reasonable and timely fashion.” From 1999 to 2008, the FCC concluded that yes, it was. But now, as more Americans than ever have broadband and use it to an often maniacal extent, the FCC has concluded for the third year in a row that no, broadband deployment is not “reasonable and timely.”

The FCC finds that 19 million Americans, mostly in very rural areas, don’t have access to fixed line terrestrial broadband. But Congress specifically asked the FCC to analyze broadband deployment using “any technology.”

“Any technology” includes DSL, cable modems, fiber-to-the-x, satellite, and of course fixed wireless and mobile. If we include wireless broadband, the unserved number falls to 5.5 million from the FCC’s headline 19 million. Five and a half million is 1.74% of the U.S. population. Not exactly a headline-grabbing figure.

Even if we stipulate the FCC’s framework, data, and analysis, we’re still left with the FCC’s own admission that between June 2010 and June 2011, an additional 7.4 million Americans gained access to fixed broadband service. That dropped the portion of Americans without access to 6% in 2011 from around 8.55% in 2010 — a 30% drop in the unserved population in one year. Most Americans have had broadband for many years, and the rate of deployment will necessarily slow toward the tail-end of any build-out. When most American households are served, there just aren’t very many to go, and those that have yet to gain access are likely to be in the very most difficult to serve areas (e.g. “on tops of mountains in the middle of nowhere”). The fact that we still added 7.4 million broadband in the last year, lowering the unserved population by 30%, even using the FCC’s faulty framework, demonstrates in any rational world that broadband “is being deployed” in a “reasonable and timely fashion.”

But this is not the rational world — it’s D.C. in the perpetual political silly season.

One might conclude that because the vast majority of these unserved Americans live in very rural areas — Alaska, Montana, West Virginia — the FCC would, if anything, suggest policies tailored to boost infrastructure investment in these hard-to-reach geographies. We could debate whether these are sound investments and whether the government would do a good job expanding access, but if rural deployment is a problem, then presumably policy should attempt to target and remediate the rural underserved. Commissioner McDowell, however, knows the real impetus for the FCC’s tortured no-confidence vote — its regulatory agenda.

McDowell notes that the report repeatedly mentions the FCC’s net neutrality rules (now being contested in court), which are as far from a pro-broadband policy, let alone a targeted one, as you could imagine. If anything, net neutrality is an impediment to broader, faster, better broadband. But the FCC is using its thumbs-down on broadband deployment to prop up its intrusions into a healthy industry. As McDowell concluded, “the majority has used this process as an opportunity to create a pretext to justify more regulation.”

Roam, roam on the range. Will Washington’s new intrusions discourage wireless expansion?

The U.S. wireless sector has been only mildly regulated over the last decade. We’d argue this is a key reason for its success. But this presumption of mostly unfettered experimentation and dynamism may be changing.

Consider Sprint’s apparent decision to use “roaming” in Oklahoma and Kansas instead of building its own network. Now, roaming is a standard feature of mobile networks worldwide. Company A might not have as much capacity as it would like in some geography, so it pays company B, who does have capacity there, for access. Company A’s customers therefore get wider coverage, and Company B is paid for use of its network.

The problem comes with the FCC’s 2011 “digital roaming” order. Last spring three FCC commissioners decided that private mobile services — which the Communications Act says “shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier” — are a common carrier. Only D.C. lawyers smarter than you and me can figure out how to transfigure “shall not” into “may.” Anyway, the possible effect is to subject mobile data — one of the fastest growing sectors anywhere on earth — to all sorts of forced access mandates and price controls.

We warned here and here that turning competitive broadband infrastructure into a “common carrier” could discourage all players in the market from building more capacity and covering wider geographies. If company A can piggyback on company B’s network at below market rates, why would it build its own expensive network? And if company B’s network capacity is going to company A’s customers, instead of its own customers, do we think company B is likely to build yet more cell sites and purchase more spectrum?

With 37 million iPhones and 15million iPads sold last quarter, we need more spectrum, more cell towers, more capacity. This isn’t the way to get it. And what we are seeing with Sprint’s decision to roam instead of build in Oklahoma and Kansas may be the tip of this anti-investment iceberg.

Last spring when the data roaming order came down we began wondering about a possible “slow walk to a reregulated communications market.” Among other items, we cited net neutrality, possible new price controls for Special Access links to cell sites, and a host of proposed regulations affecting things like behavioral advertising and intellectual property (see, PIPA/SOPA). Since then we’ve seen the government block the AT&T-T-Mobile merger. And the FCC is now holding up its own important push for more wireless spectrum because it wants the right to micromanage who gets what spectrum and how mobile carriers can use it.

Many of these items can be thoughtfully debated. But the number of new encroachments onto the communications sector threatens to slow its growth. Many of these encroachments, moreover, are taking place outside any basic legislative authority. In the digital roaming and net neutrality cases, for example, the FCC appeared clearly to grant itself extra- if not il-legal authority. These new regulations are now being challenged in court.

We need some restraint across the board on these matters. The Internet is too important. We can’t allow a quiet, gradual reregulation of the sector to slow down our chief engine of economic growth.

— Bret Swanson

Broadband Bridges to Rural America

A host of telecom and cable companies today announced a new plan to reform the Universal Service Fund and extend broadband further into rural America. I’ve spent years only partially understanding how USF works. Or how it doesn’t work, as seems the case. I think even in the old days, when it may have made some kind of sense, USF probably retarded investment and new technology in the areas it aimed to support. Unsubsidized potential entrants sporting new technologies couldn’t hope to compete with heavily subsidized incumbents. Even incumbents effectively couldn’t deploy newer, more efficient unsubsidized technologies. The result was probably some extension of phone service in the early days but lots of stagnation for decades after that. In today’s communications market, however, where many companies and many technologies supply many wholesale, commercial, and consumer services — and where broadband, Internet cloud, and wireless complement, compete, and overlap — USF has really broken down. Reform is long overdue, and this consensus industry plan should finally help move USF into the Internet age.

The new proposal — called America’s Broadband Connectivity Plan — also reforms the antiquated and broken Inter Carrier Compensation system, which sets the terms for traffic exchange among communications companies. In a broadband-mobile-Internet world, ICC, like USF, no longer works and is often exploited with arbitrage schemes that add no value but shuffle money via clever manipulation of the rules.

For too long wrangling and indecision between industry and government — and among industry players themselves — has delayed action. We now have a good consensus leap on the road to modernization.

The Slow Walk to a Reregulated Communications Market

The generally light-touch regulatory approach to America’s Internet industry has been a big success story. Broadband, wireless, digital devices, Internet content and apps — these technology sectors have exploded over the last half-dozen years, even through the Great Recession.

So why are Washington regulators gradually encroaching on the Net’s every nook and cranny? Perhaps the explanation is a paraphrased line about Washington’s upside-down ways: If it fails, subsidize it. If it succeeds, tax it. And if it succeeds wildly, regulate it.

Whatever the reason, we should watch out and speak up, lest D.C. do-gooders slow the growth of our most dynamic economic engine.

Last December, the FCC imposed a watered down version of Net Neutrality. A few weeks ago the FCC asserted authority to regulate prices and terms in the data roaming market for mobile phones. There are endless Washington proposals to regulate digital advertising markets and impose strict new rules to (supposedly) protect consumer privacy. The latest new idea (but surely not the last) is to regulate prices and terms of “special access,” or Internet connectivity in the middle of the network.

Special access refers to high-speed links that connect, say, cell phone towers to the larger network, or an office building to a metro fiber ring. Another common name for these network links is “backhaul.” Washington lobbyists have for years been trying to get the FCC to dictate terms in this market, without success. But now, as part of the proposed AT&T-T-Mobile merger, they are pushing harder than ever to incorporate regulation of these high-speed Internet lines into the government’s prospective approval of the acquisition.

As the chief opponent of the merger, Sprint especially is lobbying for the new regulations. Sprint claims that just a few companies control most the available backhaul links to its cell phone towers and wants the FCC to set rates and terms for its backhaul leases. But from the available information, it’s clear that many companies — not just Verizon and AT&T — provide these Special Access backhaul services. It’s not clear why an AT&T-T-Mobile combination should have a big effect on the market, nor why the FCC should use the event to regulate a well-functioning market.

Sprint is a majority owner and major partner of 4G mobile network Clearwire, which uses its own microwave wireless links for 90% of its backhaul capacity. Sprint used Clearwire backhaul for its Xohm Wi-Max network beginning in 2008 and will pay Clearwire around a billion dollars over the next two years to lease backhaul capacity.

T-Mobile, meanwhile, uses mostly non-AT&T, non-Verizon backhaul for its towers. Recent estimates say something like 80% of T-Mobile sites are linked by smaller Special Access providers like Bright House, FiberNet, Zayo Bandwidth, and IP Networks. Lots of other providers exist, from the large cable companies like Comcast, Cox, and TimeWarner to smaller specialty firms like FiberTower and TowerCloud to large backbone providers like Level 3. The cable companies all report fast growing cell site backhaul sales, accounting for large shares of their wholesale revenue.

One of the rationales for AT&T’s purchase of T-Mobile was that the two companies’ cell sites are complementary, not duplicative, meaning AT&T may not have links to many or most of T-Mobile’s sites. So at least in the short term it’s likely the T-Mobile cells will continue to use their existing backhaul providers, who are, again, mostly not Verizon or AT&T. It’s possible over time AT&T would expand its network and use its own links to serve the sites, but the backhaul business by then will only be more competitive than today.

This is a mostly unseen part of the Internet. Few of us every think about Special Access or Backhaul when we fire up our Blackberry, Android, or iPhone. But these lines are key components in mobile ecosystem, essential to delivering the voices and bits to and from our phones, tablets, and laptops. The wireless industry, moreover, is in the midst of a massive upgrade of its backhaul lines to accommodate first 3G and now 4G networks that will carry ever richer multimedia content. This means replacing the old T-1 and T-3 copper phone lines with new fiber optic lines and high-speed radio links. These are big investments in a very competitive market.

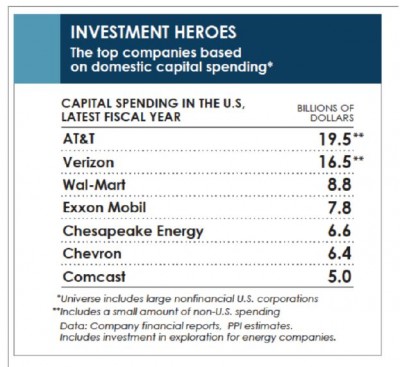

Given the Internet industry’s overwhelming contribution to the U.S. economy — not just as an innovative platform but as a leading investor in the capital base of the nation — one might think we wouldn’t lightly trifle with success. The chart below, compiled by economist Michael Mandel, shows that the top two — and three out of the top seven — domestic investors are communications companies. These are huge sums of money supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs directly and many millions indirectly.

We’ve seen the damage micromanagement can cause — in the communications sector no less. The type of regulation of prices and terms on infrastructure leases now proposed for Special Access was, in my view, a key to the 2000 tech/telecom crash. FCC intrusions (remember line sharing, TELRIC, and UNE-P, etc.) discouraged investments in the first generation of broadband. We fell behind nations like Korea. Over the last half-dozen years, however, we righted our communications ship and leapt to the top of the world in broadband and especially mobile services.

I’m not arguing these regulations would crash the sector. But the accumulated costs of these creeping Washington intrusions could disrupt the crucial price mechanisms and investment incentives that are no where more important than the fastest growing, most dynamic markets, like mobile networks.Time for FCC lawyers to hit the beach — for Memorial Day weekend . . . and beyond. They should sit back and enjoy the stupendous success of the sector they oversee. The market is working.

— Bret Swanson

Up-is-down data roaming vote could mean mobile price controls

Section 332(c)(2) of the Communications Act says that “a private mobile service shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier for any purpose under this Act.”

So of course the Federal Communications Commission on Thursday declared mobile data roaming (which is a private mobile service) a common carrier. Got it? The law says “shall not.” Three FCC commissioners say, We know better.

This up-is-down determination could allow the FCC to impose price controls on the dynamic broadband mobile Internet industry. Up-is-down legal determinations for the FCC are nothing new. After a decade trying, I’ve still not been able to penetrate the legal realm where “shall not” means “may.” Clearly the FCC operates in some alternate jurisprudential universe.

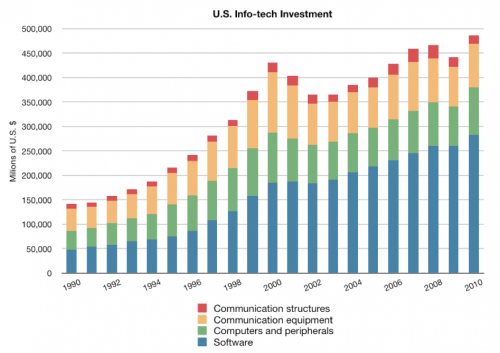

I do know the decision’s practical effect could be to slow mobile investment and innovation. It takes lots of money and know-how to build the Internet and beam real-time videos from anywhere in the world to an iPad as you sit on your comfy couch or a speeding train. Last year the U.S. invested $489 billion in info-tech, which made up 47% of all non-structure capital expenditures. Two decades ago, info-tech comprised just 33% of U.S. non-structure capital investment. This is a healthy, growing sector.

As I noted a couple weeks ago,

You remember that “roaming” is when service provider A pays provider B for access to B’s network so that A’s customers can get service when they are outside A’s service area, or where it has capacity constraints, or for redundancy. These roaming agreements are numerous and have always been privately negotiated. The system works fine.

But now a group of provider A’s, who may not want to build large amounts of new network capacity to meet rising demand for mobile data, like video, Facebook, Twitter, and app downloads, etc., want the FCC to mandate access to B’s networks at regulated prices. And in this case, the B’s have spent many tens of billions of dollars in spectrum and network equipment to provide fast data services, though even these investments can barely keep up with blazing demand. . . .

It is perhaps not surprising that a small number of service providers who don’t invest as much in high-capacity networks might wish to gain artificially cheap access to the networks of the companies who invest tens of billions of dollars per year in their mobile networks alone. Who doesn’t like lower input prices? Who doesn’t like his competitors to do the heavy lifting and surf in his wake? But the also not surprising result of such a policy could be to reduce the amount that everyone invests in new networks. And this is simply an outcome the technology industry, and the entire country, cannot afford. The FCC itself has said that “broadband is the great infrastructure challenge of the early 21st century.”

But if Washington actually wants more infrastructure investment, it has a funny way of showing it. On Sunday at a Boston conference organized by Free Press, former Obama White House technology advisor Susan Crawford talked about America’s major communications companies. “[R]egulating these guys into to an inch of their life is exactly what needs to happen,” she said. You’d think the topic was tobacco or human trafficking rather than the companies that have pretty successfully brought us the wonders of the Internet.

It’s the view of an academic lawyer who has never visited that exotic place called the real world. Does she think that the management, boards, and investors of these companies will continue to fund massive infrastructure projects in the tens of billions of dollars if Washington dangles them within “an inch of their life”? Investment would dry up long before we ever saw the precipice. This is exactly what’s happened economy-wide over the last few years as every company, every investor, in every industry worried about Washington marching them off the cost cliff. The White House supposedly has a newfound appreciation for the harms of over-regulation and has vowed to rein in the regulators. But in case after case, it continues to toss more regulatory pebbles into the economic river.

Perhaps Nick Schulz of the American Enterprise Institute has it right. Take a look. He calls it the Tommy Boy theory of regulation, and just maybe it explains Washington’s obsession — yes, obsession; when you watch the video, you will note that is the correct word — with managing every nook and cranny of the economy.

International Broadband Comparison, continued

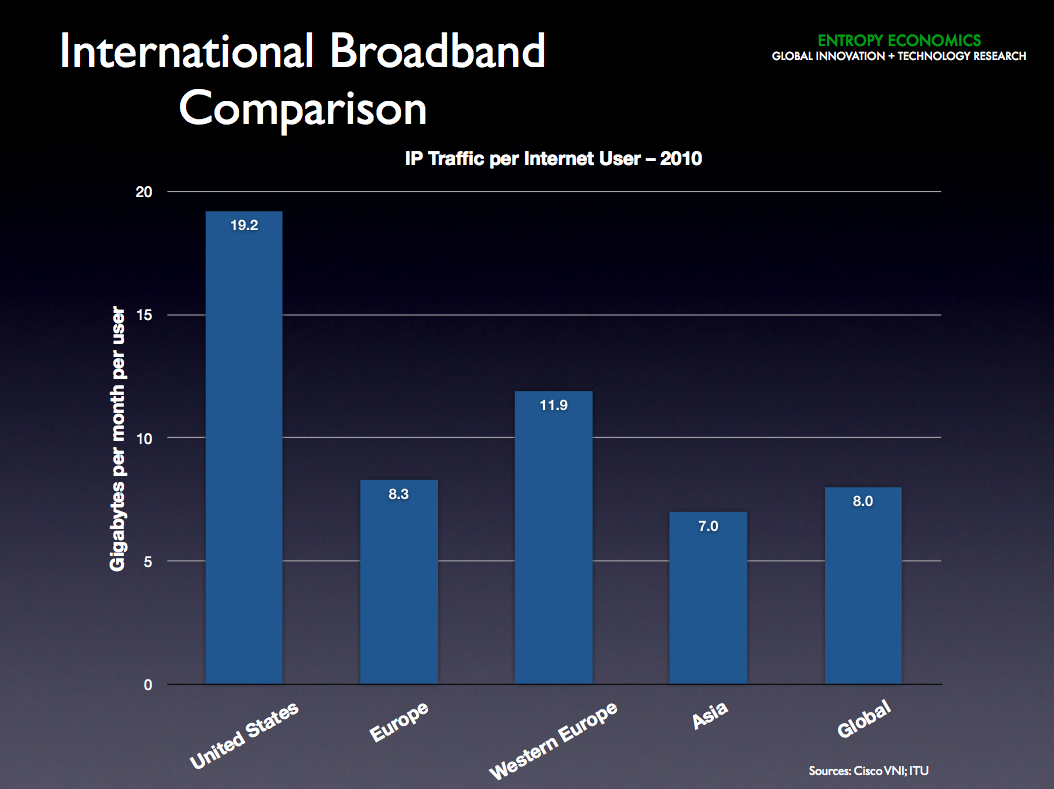

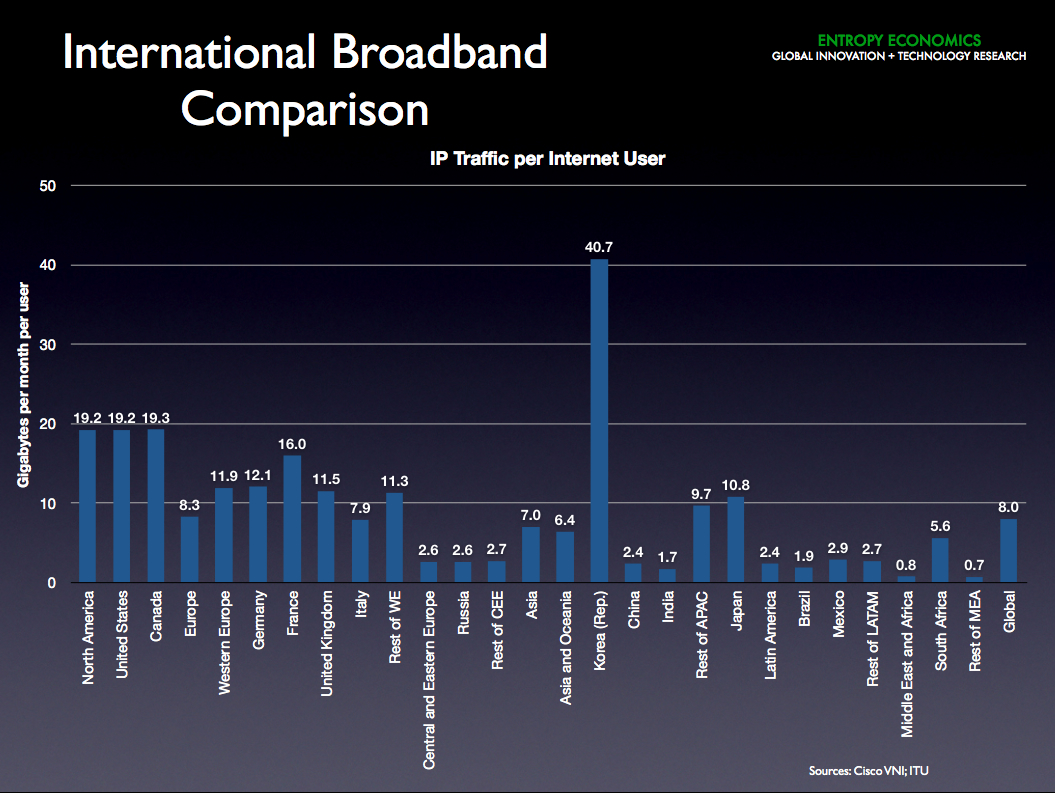

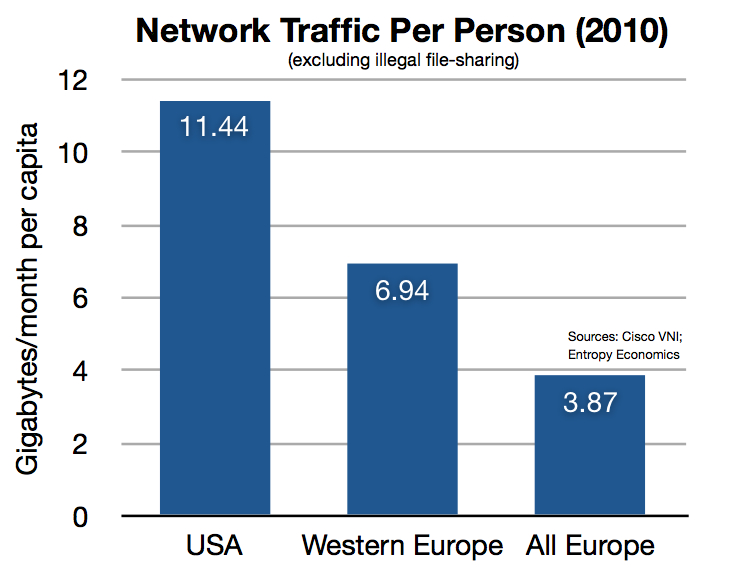

New numbers from Cisco allow us to update our previous comparison of actual Internet usage around the world. We think this is a far more useful metric than the usual “broadband connections per 100 inhabitants” used by the OECD and others to compile the oft-cited world broadband rankings.

What the per capita metric really measures is household size. And because the U.S. has more people in each household than many other nations, we appear worse in those rankings. But as the Phoenix Center has noted, if each OECD nation reached 100% broadband nirvana — i.e., every household in every nation connected — the U.S. would actually fall from 15th to 20th. Residential connections per capita is thus not a very illuminating measure.

But look at the actual Internet traffic generated and consumed in the U.S.

The U.S. far outpaces every other region of the world. In the second chart, you can see that in fact only one nation, South Korea, generates significantly more Internet traffic per user than the U.S. This is no surprise. South Korea was the first nation to widely deploy fiber-to-the-x and was also the first to deploy 3G mobile, leading to not only robust infrastructure but also a vibrant Internet culture. The U.S. dwarfs most others.

If the U.S. was so far behind in broadband, we could not generate around twice as much network traffic per user compared to nations we are told far exceed our broadband capacity and connectivity. The U.S. has far to go in a never-ending buildout of its communications infrastructure. But we invest more than other nations, we’ve got better broadband infrastructure overall, and we use broadband more — and more effectively (see the Connectivity Scorecard and The Economist’s Digital Economy rankings) — than almost any other nation.

The conventional wisdom on this one is just plain wrong.

The Regulatory Threat to Web Video

See our commentary at Forbes.com, responding to Revision3 CEO Jim Louderback’s calls for Internet regulation.

What we have here is “mission creep.” First, Net Neutrality was about an “open Internet” where no websites were blocked or degraded. But as soon as the whole industry agreed to these perfectly reasonable Open Web principles, Net Neutrality became an exercise in micromanagement of network technologies and broadband business plans. Now, Louderback wants to go even further and regulate prices. But there’s still more! He also wants to regulate the products that broadband providers can offer.

A Victory For the Free Web

After yesterday’s federal court ruling against the FCC’s overreaching net neutrality regulations, which we have dedicated considerable time and effort combatting for the last seven years, Holman Jenkins says it well:

Hooray. We live in a nation of laws and elected leaders, not a nation of unelected leaders making up rules for the rest of us as they go along, whether in response to besieging lobbyists or the latest bandwagon circling the block hauled by Washington’s permanent “public interest” community.

This was the reassuring message yesterday from the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals aimed at the Federal Communications Commission. Bottom line: The FCC can abandon its ideological pursuit of the “net neutrality” bogeyman, and get on with making the world safe for the iPad.

The court ruled in considerable detail that there’s no statutory basis for the FCC’s ambition to annex the Internet, which has grown and thrived under nobody’s control.

. . .

So rather than focusing on new excuses to mess with network providers, the FCC should tackle two duties unambiguously before it: Figure out how to liberate the nation’s wireless spectrum (over which it has clear statutory authority) to flow to more market-oriented uses, whether broadband or broadcast, while also making sure taxpayers get adequately paid as the current system of licensed TV and radio spectrum inevitably evolves into something else.

Second: Under its media ownership hat, admit that such regulation, which inhibits the merger of TV stations with each other and with newspapers, is disastrously hindering our nation’s news-reporting resources and brands from reshaping themselves to meet the opportunities and challenges of the digital age. (Willy nilly, this would also help solve the spectrum problem as broadcasters voluntarily redeployed theirs to more profitable uses.)

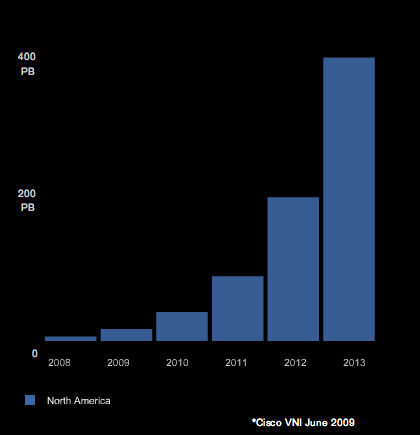

More wireless connectivity? Or more politics?

For years we’ve been talking about the need for more wireless bandwidth, more spectrum, and a host of creative new strategies to complement our mobile phone networks — from familiar Wi-Fi to more exotic femtocells and satellites. The continuing explosion of mobile data traffic means we need these things now more than ever. In the graph below, Cisco projects 120% compound annual growth in North American mobile data from 2009 through 2013.

The Federal Communications Commission recognized these trends and needs in its new National Broadband Plan. It set the bold goal of unleashing 500 MHz of mostly dormant wireless spectrum for more productive use in new broadband Internet and media applications.

On March 29, the FCC had a chance to begin putting its Plan into action when it approved the acquisition of SkyTerra by Harbinger Capital. The result of the merger is a new wireless company that will use both MSS satellite spectrum and so-called ATC terrestrial spectrum to deliver a new hybrid mobile service. Harbinger announced it would build a nationwide, wholesale, “open access” 4G broadband wireless network at the cost of $6 billion. Although not part of the FCC’s 500 MHz push, the new Harbinger strategy aligns nicely with the goal of more, better, and broader wireless access and options throughout the country (in this case, Canada, too).

But the FCC order, which was not voted by the full commission but issued by the bureau chiefs, contains two curious provisions. The provisions restrict Harbinger’s cooperation with two important mobile service providers and could hinder the very goal of extending more wireless coverage to more Americans. (more…)

Quote of the Day

“Architects of the legislation that binds the nation’s communications infrastructure in the year 2010 were born in the 1870s and 1880s. There is talk today in Washington about categorizing technologies and platforms developed in the 21st century under different Titles of legislation written by people born in the 19th century. We don’t need to jettison all the wisdom of the ancients, but perhaps there’s a better way?”

— Nick Shulz, at the Enterprise Blog, March 25, 2010

Chronically Critical Broadband Country Comparisons

With the release of the FCC’s National Broadband Plan, we continue to hear all sorts of depressing stories about the sorry state of American broadband Internet access. But is it true?

International comparisons in such a fast-moving arena as tech and communications are tough. I don’t pretend it is easy to boil down a hugely complex topic to one right answer, but I did have some critical things to say about a major recent report that got way too many things wrong. A new article by that report’s author singled out France as especially more advanced than the U.S. To cut through all the clutter of conflicting data and competing interpretations on broadband deployment, access, adoption, prices, and speeds, however, maybe a simple chart will help.

Here we compare network usage. Not advertised speeds, which are suspect. Not prices which can be distorted by the use of purchasing power parity (PPP). Not “penetration,” which is largely a function of income, urbanization, and geography. No, just simply, how much data traffic do various regions create and consume.

If U.S. networks were so backward — too sparse, too slow, too expensive — would Americans be generating 65% more network traffic per capita than their Western European counterparts?

Washington liabilities vs. innovative assets

Our new article at RealClearMarkets:

As Washington and the states pile up mountainous liabilities — $3 trillion for unfunded state pensions, $10 trillion in new federal deficits through 2019, and $38 trillion (or is it $50 trillion?) in unfunded Medicare promises — the U.S. needs once again to call on its chief strategic asset: radical innovation.

One laboratory of growth will continue to be the Internet. The U.S. began the 2000’s with fewer than five million residential broadband lines and zero mobile broadband. We begin the new decade with 71 million residential lines and 300 million portable and mobile broadband devices. In all, consumer bandwidth grew almost 15,000%.

Even a thriving Internet, however, cannot escape Washington’s eager eye. As the Federal Communications Commission contemplates new “network neutrality” regulation and even a return to “Title II” telephone regulation, we have to wonder where growth will come from in the 2010’s . . . .

Did the FCC get the White House jobs memo?

That’s the question I ask in this Huffington Post article today.

Media Disruptions

Just two more New York Times articles that point out what’s obvious around here: the Internet’s dramatic and unpredictable disruption of the whole “media” space. Isn’t Washington’s assumption that it can sort all this out and impose particular business models on the media space through prescriptive Net Neutrality regulation, a case of supreme hubris?