Brink Lindsey of the Kauffman Foundation summarizes a new paper on the imperative of constantly exploring the economic frontier:

Up-is-down data roaming vote could mean mobile price controls

Section 332(c)(2) of the Communications Act says that “a private mobile service shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier for any purpose under this Act.”

So of course the Federal Communications Commission on Thursday declared mobile data roaming (which is a private mobile service) a common carrier. Got it? The law says “shall not.” Three FCC commissioners say, We know better.

This up-is-down determination could allow the FCC to impose price controls on the dynamic broadband mobile Internet industry. Up-is-down legal determinations for the FCC are nothing new. After a decade trying, I’ve still not been able to penetrate the legal realm where “shall not” means “may.” Clearly the FCC operates in some alternate jurisprudential universe.

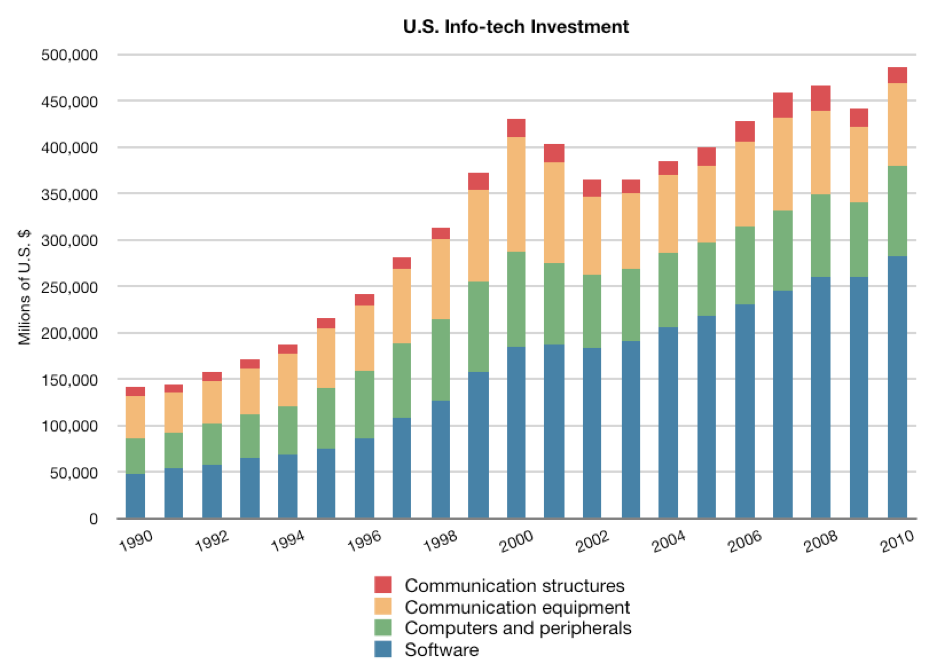

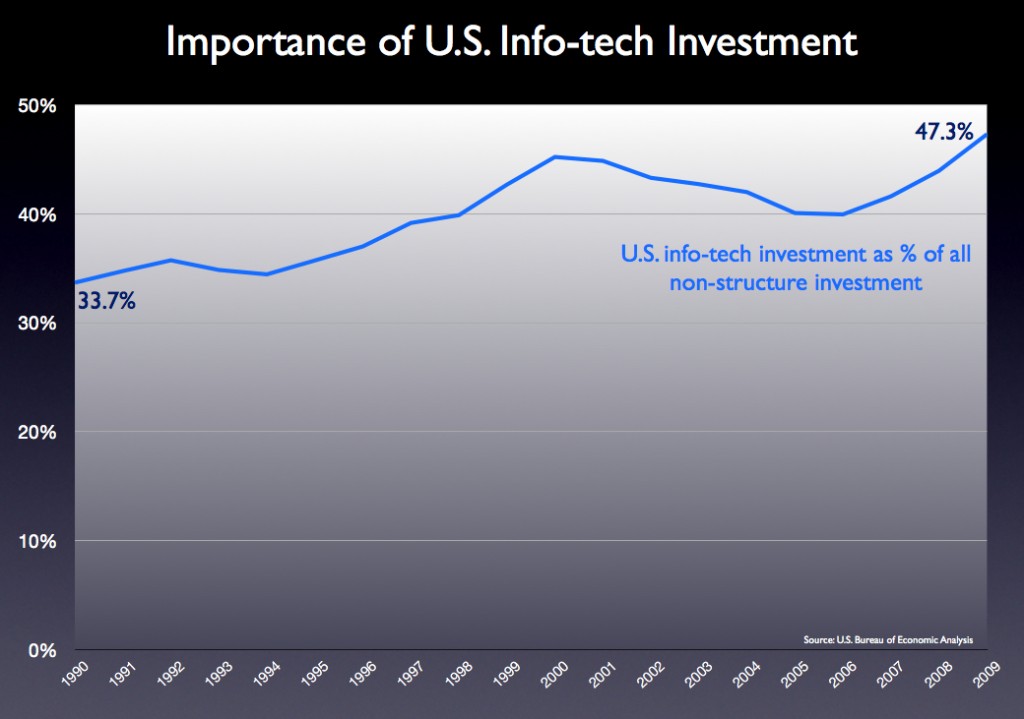

I do know the decision’s practical effect could be to slow mobile investment and innovation. It takes lots of money and know-how to build the Internet and beam real-time videos from anywhere in the world to an iPad as you sit on your comfy couch or a speeding train. Last year the U.S. invested $489 billion in info-tech, which made up 47% of all non-structure capital expenditures. Two decades ago, info-tech comprised just 33% of U.S. non-structure capital investment. This is a healthy, growing sector.

As I noted a couple weeks ago,

You remember that “roaming” is when service provider A pays provider B for access to B’s network so that A’s customers can get service when they are outside A’s service area, or where it has capacity constraints, or for redundancy. These roaming agreements are numerous and have always been privately negotiated. The system works fine.

But now a group of provider A’s, who may not want to build large amounts of new network capacity to meet rising demand for mobile data, like video, Facebook, Twitter, and app downloads, etc., want the FCC to mandate access to B’s networks at regulated prices. And in this case, the B’s have spent many tens of billions of dollars in spectrum and network equipment to provide fast data services, though even these investments can barely keep up with blazing demand. . . .

It is perhaps not surprising that a small number of service providers who don’t invest as much in high-capacity networks might wish to gain artificially cheap access to the networks of the companies who invest tens of billions of dollars per year in their mobile networks alone. Who doesn’t like lower input prices? Who doesn’t like his competitors to do the heavy lifting and surf in his wake? But the also not surprising result of such a policy could be to reduce the amount that everyone invests in new networks. And this is simply an outcome the technology industry, and the entire country, cannot afford. The FCC itself has said that “broadband is the great infrastructure challenge of the early 21st century.”

But if Washington actually wants more infrastructure investment, it has a funny way of showing it. On Sunday at a Boston conference organized by Free Press, former Obama White House technology advisor Susan Crawford talked about America’s major communications companies. “[R]egulating these guys into to an inch of their life is exactly what needs to happen,” she said. You’d think the topic was tobacco or human trafficking rather than the companies that have pretty successfully brought us the wonders of the Internet.

It’s the view of an academic lawyer who has never visited that exotic place called the real world. Does she think that the management, boards, and investors of these companies will continue to fund massive infrastructure projects in the tens of billions of dollars if Washington dangles them within “an inch of their life”? Investment would dry up long before we ever saw the precipice. This is exactly what’s happened economy-wide over the last few years as every company, every investor, in every industry worried about Washington marching them off the cost cliff. The White House supposedly has a newfound appreciation for the harms of over-regulation and has vowed to rein in the regulators. But in case after case, it continues to toss more regulatory pebbles into the economic river.

Perhaps Nick Schulz of the American Enterprise Institute has it right. Take a look. He calls it the Tommy Boy theory of regulation, and just maybe it explains Washington’s obsession — yes, obsession; when you watch the video, you will note that is the correct word — with managing every nook and cranny of the economy.

AT&T’s Exaflood Acquisition Good for Mobile Consumers and Internet Growth

AT&T’s announced purchase of T-Mobile is an exaflood acquisition — a response to the overwhelming proliferation of mobile computers and multimedia content and thus network traffic. The iPhone, iPad, and other mobile devices are pushing networks to their limits, and AT&T literally could not build cell sites (and acquire spectrum) fast enough to meet demand for coverage, capacity, and quality. Buying rather than building new capacity improves service today (or nearly today) — not years from now. It’s a home run for the companies — and for consumers.

AT&T’s announced purchase of T-Mobile is an exaflood acquisition — a response to the overwhelming proliferation of mobile computers and multimedia content and thus network traffic. The iPhone, iPad, and other mobile devices are pushing networks to their limits, and AT&T literally could not build cell sites (and acquire spectrum) fast enough to meet demand for coverage, capacity, and quality. Buying rather than building new capacity improves service today (or nearly today) — not years from now. It’s a home run for the companies — and for consumers.

We’re nearing 300 million mobile subscribers in the U.S., and Strategy Analytics estimates by 2014 we’ll add an additional 60 million connected devices like tablets, kiosks, remote sensors, medical monitors, and cars. All this means more connectivity, more of the time, for more people. Mobile data traffic on AT&T’s network rocketed 8,000% in the last four years. Remember that just a decade ago there was essentially no wireless data traffic. It was all voice traffic. A few rudimentary text applications existed, but not much more. By year-end 2010, AT&T was carrying around 12 petabytes per month of mobile traffic alone. The company expects another 8 to 10-fold rise over the next five years, when its mobile traffic could reach 150 petabytes per month. (We projected this type of growth in a series of reports and articles over the last decade.)

The two companies’ networks and businesses are so complementary that AT&T thinks it can achieve $40 billion in cost savings. That’s more than the $39-billion deal price. Those huge efficiencies should help keep prices low in a market that already boasts the lowest prices in the world (just $0.04 per voice minute versus, say, $0.16 in Europe).

But those who focus only on the price of existing products (like voice minutes) and traditional metrics of “competition,” like how many national service providers there are, will miss the boat. Pushing voice prices down marginally from already low levels is not the paramount objective. Building fourth generation mobile multimedia networks is. Some wonder whether “consolidation of power could eventually lead to higher prices than consumers would otherwise see.” But “otherwise” assumes a future that isn’t going to happen. T-Mobile doesn’t have the spectrum or financial wherewithal to deploy a full 4G network. So the 4G networks of AT&T, Verizon, and Sprint (in addition to Clearwire and LightSquared) would have been competing against the 3G network of T-Mobile. A 3G network can’t compete on price with a 4G network because it can’t offer the same product. In many markets, inferior products can act as partial substitutes for more costly superior products. But in the digital world, next gen products are so much better and cheaper than the previous versions that older products quickly get left behind. Could T-Mobile have milked its 3G network serving mostly voice customers at bargain basement prices? Perhaps. But we already have a number of low-cost, bare-bones mobile voice providers.

The usual worries from the usual suspects in these merger battles go like this: First, assume a perfect market where all products are commodities, capacity is unlimited yet technology doesn’t change, and competitors are many. Then assume a drastic reduction in the number of competitors with no prospect of new market entrants. Then warn that prices could spike. It’s a story that may resemble some world, but not the one in which we live.

The merger’s boost to cell-site density is hugely important and should not be overlooked. Yes, we will simultaneously be deploying lots of new Wi-Fi nodes and femtocells (little mobile nodes in offices and homes), which help achieve greater coverage and capacity, but we still need more macrocells. AT&T’s acquisition will boost its total number of cell sites by 30%. In major markets like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago, the number of AT&T cell sites will grow by 25%-45%. In many areas, total capacity should double.

It’s not easy to build cell sites. You’ve got to find good locations, get local government approvals, acquire (or lease) the sites, plan the network, build the tower and network base station, connect it to your long-haul network with fiber-optic lines, and of course pay for it. In the last 20 years, the number of U.S. cell sites has grown from 5,000 to more than 250,000, but we still don’t have nearly enough. CEO Randall Stephenson says the T-Mobile purchase will achieve almost immediately a network expansion that would have taken five years through AT&T’s existing organic growth plan. Because of the nature of mobile traffic — i.e., it’s mobile and bandwidth is shared — the combination of the two networks should yield a more-than-linear increase in quality improvements. The increased cell-site density will give traffic planners much more flexibility to deliver high-capacity services than if the two companies operated separately.

The U.S. today has the most competitive mobile market in the world (second, perhaps, only to tiny Hong Kong). Yes, it’s true, even after the merger, the U.S. will still have a more “competitive” market than most. But “competition” is often not the most — or even a very — important metric in these fast moving markets. In periods of undershoot, where a technology is not good enough to meet demand on quantity or quality, you often need integration to optimize the interfaces and the overall experience, a la the hand-in-glove paring of the iPhone’s hardware, software, and network. Streaming a video to a tiny piece of plastic in your pocket moving at 60 miles per hour — with thousands of other devices competing for the same bandwidth — is not a commodity service. It’s very difficult. It requires millions of things across the network to go just right. These services often take heroic efforts and huge sums of capital just to make the systems work at all.

Over time technologies overshoot, markets modularize, and small price differences matter more. Products that seem inferior but which are “good enough” then begin to disrupt state-of-the art offerings. This was what happened to the voice minute market over the last 20 years. Voice-over-IP, which initially was just “good enough,” made voice into a commodity. Competition played a big part, though Moore’s law was the chief driver of falling prices. Now that voice is close to free (though still not good enough on many mobile links) and data is king, we see the need for more integration to meet the new challenges of the multimedia exaflood. It’s a never ending, dynamic cycle. (For much more on this view of technology markets, see Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen).

The merger will have its critics, but it seriously accelerates the coming of fourth generation mobile networks and the spread of broadband across America.

— Bret Swanson

Data roaming mischief . . . Another pebble in the digital river?

Mobile communications is among the healthiest of U.S. industries. Through a time of economic peril and now merely uncertainty, mobile innovation hasn’t wavered. It’s been a too-rare bright spot. Huge amounts of infrastructure investment, wildly proliferating software apps, too many devices to count. If anything, the industry is moving so fast on so many fronts that we risk not keeping up with needed capacity.

Mobile, perhaps not coincidentally, has also been historically a quite lightly regulated industry. But emerging is a sort of slow boil of small but many rules, or proposed rules, that could threaten the sector’s success. I’m thinking of the “bill shock” proceeding, in which the FCC is looking at billing practices and various “remedies.” And the failure to settle the D block public safety spectrum issue in a timely manner. And now we have a group of rural mobile providers who want the FCC to set prices in the data roaming market.

You remember that “roaming” is when service provider A pays provider B for access to B’s network so that A’s customers can get service when they are outside A’s service area, or where it has capacity constraints, or for redundancy. These roaming agreements are numerous and have always been privately negotiated. The system works fine.

But now a group of provider A’s, who may not want to build large amounts of new network capacity to meet rising demand for mobile data, like video, Facebook, Twitter, and app downloads, etc., want the FCC to mandate access to B’s networks at regulated prices. And in this case, the B’s have spent many tens of billions of dollars in spectrum and network equipment to provide fast data services, though even these investments can barely keep up with blazing demand.

The FCC has never regulated mobile phone rates, let alone data rates, let alone data roaming rates. And of course mobile voice and data rates have been dropping like rocks. These few rural providers are asking the FCC to step in where it hasn’t before. They are asking the FCC to impose old-time common carrier regulation in a modern competitive market – one in which the FCC has no authority to impose common carrier rules and prices.

In the chart above, we see U.S. info-tech investment in 2010 approached $500 billion. Communications equipment and structures (like cell phone towers) surpassed $105 billion. The fourth generation of mobile networks is just in its infancy. We will need to invest many tens of billions of dollars each year for the foreseeable future both to drive and accommodate Internet innovation, which spreads productivity enhancements and wealth across every sector in the economy.

It is perhaps not surprising that a small number of service providers who don’t invest as much in high-capacity networks might wish to gain artificially cheap access to the networks of the companies who invest tens of billions of dollars per year in their mobile networks alone. Who doesn’t like lower input prices? Who doesn’t like his competitors to do the heavy lifting and surf in his wake? But the also not surprising result of such a policy could be to reduce the amount that everyone invests in new networks. And this is simply an outcome the technology industry, and the entire country, cannot afford. The FCC itself has said that “broadband is the great infrastructure challenge of the early 21st century.”

Economist Michael Mandel has offered a useful analogy:

new regulations [are] like tossing small pebbles into a stream. Each pebble by itself would have very little effect on the flow of the stream. But throw in enough small pebbles and you can make a very effective dam.

Why does this happen? The answer is that each pebble by itself is harmless. But each pebble, by diverting the water into an ever-smaller area, creates a ‘negative externality’ that creates more turbulence and slows the water flow.

Similarly, apparently harmless regulations can create negative externalities that add up over time, by forcing companies to spending time and energy meeting the new requirements. That reduces business flexibility and hurts innovation and growth.

It may be true that none of the proposed new rules for wireless could alone bring down the sector. But keep piling them up, and you can dangerously slow an important economic juggernaut. Price controls for data roaming are a terrible idea.

John Cochrane’s “Unpleasant Fiscal Arithmetic”

Can economic growth stop the coming fiscal inflation?

See my new Forbes column on the puzzling economic outlook and a new way to think about monetary policy . . . .

An Economic Solution to the D Block Dilemma

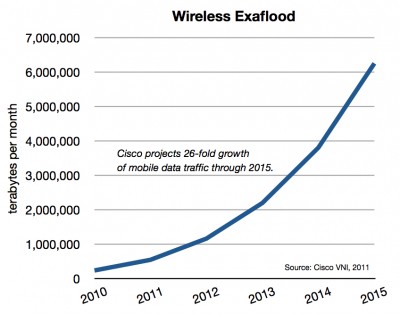

Last month, Cisco reported that wireless data traffic is growing faster than projected (up 159% in 2010 versus its estimate of 149%). YouTube illustrated the point with its own report that mobile views of its videos grew 3x last year to over 200 million per day. Tablets like the Apple iPad were part of the upside surprise.

Last month, Cisco reported that wireless data traffic is growing faster than projected (up 159% in 2010 versus its estimate of 149%). YouTube illustrated the point with its own report that mobile views of its videos grew 3x last year to over 200 million per day. Tablets like the Apple iPad were part of the upside surprise.

The very success of smartphones, tablets, and all the new mobile form-factors fuels frustration. They are never fast enough. We always want more capacity, less latency, fewer dropped calls, and ubiquitous access. In a real sense, these are good problems to have. They reflect a fast-growing sector delivering huge value to consumers and businesses. Rapid growth, however, necessarily strains various nodes in the infrastructure. At some point, a lack of resources could stunt this upward spiral. And one of the most crucial resources is wireless spectrum.

There is broad support for opening vast swaths of underutilized airwaves — 300 megahertz (MHz) by 2015 and 500 MHz overall — but we first must dispose of one spectrum scuffle known as the “D block.” Several years ago in a previous spectrum auction, the FCC offered up 10 MHz for commercial use — with the proviso that the owner would have to share the spectrum with public safety users (police, fire, emergency) nationwide. This “D block” sat next to an additional 10 MHz known as Public Safety Broadband (PSB), which was granted outright to the public safety community. But the D block auction failed. Potential bidders could not reconcile the technical and business complexities of this “encumbered” spectrum. The FCC received just one D block bid for just $472 million, far below the FCC’s minimum acceptable bid of $1.3 billion. So today, three years after the failed auction and almost a decade after 9/11, we still have not resolved the public safety spectrum question. (more…)

A History, A Theory, An Exaflood

My friendly UPS guy just dropped off two copies of James Gleick’s new book The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood. Haven’t anticipated a book this eagerly in a long time.

Will be back with my thoughts after I read this 500-pager. For now, a few of today’s high-profile reviews of the book: Nick Carr in The Daily Beast and John Horgan in The Wall Street Journal. And, of course, Freeman Dyson’s terrific essay in the NY Review of Books.

Cloud Wars Baffle Simmering Cyber Lawyers

My latest column in Forbes – “Cloud Wars Baffle Simmering Cyber Lawyers”:

Like their celestial counterparts, cyber clouds are unpredictable and ever-changing. The Motorola Xoom tablet arrived on Tuesday. The Apple iPad II arrives next week. Just as Verizon finally boasts its own iPhone, AT&T turns the tables with the Motorola Atrix running on the even faster growing Google Android platform. Meanwhile, Nokia declares its once-mighty Symbian platform ablaze and abandons ship for a new mobile partnership with Microsoft.

In the media world, Apple pushes the envelope with publishers who use iPhone and iPad apps to deliver content. Its new subscription service seeks 30% of the price of magazines, newspapers, and, it hopes, games and videos delivered through its App Store and iTunes.

Google quickly counters with OnePass, a program that charges content providers 10% for access to its Android mobile platform. But unlike Apple, said Google CEO Eric Schmidt, “We don’t prevent you from knowing, if you’re a publisher, who your customers are.” Game on.

Netflix, by the way, saw its Web traffic spike 38% in just one month between December 2010 and January 2011 and is, ho hum, upending movies, cable, and TV.

As the cloud wars roar, the cyber lawyers simmer. This wasn’t how it was supposed to be. The technology law triad of Harvard’s Lawrence Lessig and Jonathan Zittrain and Columbia’s Tim Wu had a vision. They saw an arts and crafts commune of cyber-togetherness. Homemade Web pages with flashing sirens and tacky text were more authentic. “Generativity” was Zittrain’s watchword, a vague aesthetic whose only definition came from its opposition to the ominous “perfect control” imposed by corporations dictating “code” and throwing the “master switch.”

In their straw world of “open” heros and “closed” monsters, AOL’s “walled garden” of the 1990s was the first sign of trouble. Microsoft was an obvious villain. The broadband service providers were of coursedangerous gatekeepers, the iPhone was too sleek and integrated, and now even Facebook threatens their ideal of uncurated chaos. These were just a few of the many companies that were supposed to kill the Internet. The triad’s perfect world would be mostly broke organic farmers and struggling artists. Instead, we got Apple’s beautifully beveled apps and Google’s intergalactic ubiquity. Worst of all, the Web started making money.

Read the full column here . . . .

Budget Blow-Out

“Over the 10-year budget window, the president plans for Washington to extract $39 trillion in taxes and spend $46 trillion. The debt limit, currently $14.3 trillion, would have to grow to over $26 trillion.

“Making matters worse, these horrendous spending, taxing and debt numbers would be even grimmer if not for the budget’s rosy assumptions. The budget assumes that real growth will climb from an already wishful 4% in 2012 to 4.5% in 2013 and 4.2% in 2014 — despite plans for sweeping tax increases. The assumed GDP growth is well over any growth rate achieved in the Bush expansion. The budget also reflects the unrealistic assumption that the Federal Reserve will be able to keep interest rates very low and generate $476 billion in profits through highly leveraged financial speculation.”

— David Malpass, The Wall Street Journal, February 16, 2011

More Stagnation

Tyler Cowen talks to Matt Yglesias about The Great Stagnation . . . . Here was my book review – “Tyler Cowen’s Techno Slump.”

World Catches On to the Exaflood

Researchers Martin Hilbert and Priscila Lopez add to the growing literature on the data explosion (what we long ago termed the “exaflood”) with a study of analog and digital information storage, transmission, and computation from 1986 through 2007. They found in 2007 globally we were able to store 290 exabytes, communicate almost 2 zettabytes, and compute around 6.4 exa-instructions per second (EIPS?) on general purpose computers. The numbers have gotten much, much larger since then. Here’s the Science paper (subscription), which appears along side an entire special issue, “Dealing With Data,” and here’s a graphic from the Washington Post:

(Thanks to @AdamThierer for flagging the WashPost article.)

The Stagnation Conversation, continued

Another review of Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation, this one by Michael Mandel. More from Brink Lindsey.

And Nick Schulz’s video interview of Cowen:

Mobile traffic grew 159% in 2010 . . . Tablets giving big boost

Among other findings in the latest version of Cisco’s always useful Internet traffic updates:

- Mobile data traffic was even higher in 2010 than Cisco had projected in last year’s report. Actual growth was 159% (2.6x) versus projected growth of 149% (2.5x).

- By 2015, we should see one mobile device per capita . . . worldwide. That means around 7.1 billion mobile devices compared to 7.2 billion people.

- Mobile tablets (e.g., iPads) are likely to generate as much data traffic in 2015 as all mobile devices worldwide did in 2010.

- Mobile traffic should grow at an annual compound rate of 92% through 2015. That would mean 26-fold growth between 2010 and 2015.

Are we doomed by The Great Stagnation?

Here are my thoughts on Tyler Cowen’s terrific new e-book essay The Great Stagnation.

Brink Lindsey of the Kauffman Foundation comments here.

UPDATE: Tyler Cowen lists more reviews of his essay here:

2. Scott Sumner buys a Kindle and reviews The Great Stagnation.

3. Forbes review of The Great Stagnation.

4. Ryan Avent review of The Great Stagnation.

Arnold Kling comments here.

And Nick Schulz here.

Akamai CEO Exposes FCC’s Confused “Paid Priority” Prohibition

In the wake of the FCC’s net neutrality Order, published on December 23, several of us have focused on the Commission’s confused and contradictory treatment of “paid prioritization.” In the Order, the FCC explicitly permits some forms of paid priority on the Internet but strongly discourages other forms.

From the beginning — that is, since the advent of the net neutrality concept early last decade — I argued that a strict neutrality regime would have outlawed, among other important technologies, CDNs, which prioritized traffic and made (make!) the Web video revolution possible.

So I took particular notice of this new interview (sub. required) with Akamai CEO Paul Sagan in the February 2011 issue of MIT’s Technology Review:

TR: You’re making copies of videos and other Web content and distributing them from strategic points, on the fly.

Paul Sagan: Or routes that are picked on the fly, to route around problematic conditions in real time. You could use Boston [as an analogy]. How do you want to cross the Charles to, say, go to Fenway from Cambridge? There are a lot of bridges you can take. The Internet protocol, though, would probably always tell you to take the Mass. Ave. bridge, or the BU Bridge, which is under construction right now and is the wrong answer. But it would just keep trying. The Internet can’t ever figure that out — it doesn’t. And we do.

There it is. Akamai and other content delivery networks (CDNs), including Google, which has built its own CDN-like network, “route around” “the Internet,” which “can’t ever figure . . . out” the fastest path needed for robust packet delivery. And they do so for a price. In other words: paid priority. Content companies, edge innovators, basement bloggers, and poor non-profits who don’t pay don’t get the advantages of CDN fast lanes. (more…)

Did the FCC order get lots worse in last two weeks?

So, here we are. Today the FCC voted 3-2 to issue new rules governing the Internet. I expect the order to be struck down by the courts and/or Congress. Meantime, a few observations:

- The order appears to be more intrusive on the topic of “paid prioritization” than was Chairman Genachowski’s outline earlier this month. (Keep in mind, we haven’t seen the text. The FCC Commissioners themselves only got access to the text at 11:42 p.m. last night.)

- If this is true, if the “nondiscrimination” ban goes further than a simple reasonableness test, which itself would be subject to tumultuous legal wrangling, then the Net Neutrality order could cause more problems than I wrote about in this December 7 column.

- A prohibition or restriction on “paid prioritization” is a silly rule that belies a deep misunderstanding of how our networks operate today and how they will need to operate tomorrow. Here’s how I described it in recent FCC comments:

In September 2010, a new network company that had operated in stealth mode digging ditches and boring tunnels for the previous 24 months, emerged on the scene. As Forbes magazine described it, this tiny new company, Spread Networks

“spent the last two years secretly digging a gopher hole from Chicago to New York, usurping the erstwhile fastest paths. Spread’s one-inch cable is the latest weapon in the technology arms race among Wall Street houses that use algorithms to make lightning-fast trades. Every day these outfits control bigger stakes of the markets – up to 70% now. “Anybody pinging both markets has to be on this line, or they’re dead,” says Jon A. Najarian, cofounder of OptionMonster, which tracks high-frequency trading.

“Spread’s advantage lies in its route, which makes nearly a straight line from a data center in Chicago’s South Loop to a building across the street from Nasdaq’s servers in Carteret, N.J. Older routes largely follow railroad rights-of-way through Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania. At 825 miles and 13.3 milliseconds, Spread’s circuit shaves 100 miles and 3 milliseconds off of the previous route of lowest latency, engineer-talk for length of delay.”

Why spend an estimated $300 million on an apparently duplicative route when numerous seemingly similar networks already exist? Because, Spread says, three milliseconds matters.

Spread offers guaranteed latency on its dark fiber product of no more than 13.33 milliseconds. Its managed wave product is guaranteed at no more than 15.75 milliseconds. It says competitors’ routes between Chicago and New York range from 16 to 20 milliseconds. We don’t know if Spread will succeed financially. But Spread is yet another demonstration that latency is of enormous and increasing importance. From entertainment to finance to medicine, the old saw is truer than ever: time is money. It can even mean life or death.

A policy implication arises. The Spread service is, of course, a form a “paid prioritization.” Companies are paying “eight to 10 times the going rate” to get their bits where they want them, when they want them.5 It is not only a demonstration of the heroic technical feats required to increase the power and diversity of our networks. It is also a prime example that numerous network users want to and will pay money to achieve better service.

One way to achieve better service is to deploy more capacity on certain links. But capacity is not always the problem. As Spread shows, another way to achieve better service is to build an entirely new 750-mile fiber route through mountains to minimize laser light delay. Or we might deploy a network of server caches that store non-realtime data closer to the end points of networks, as many Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) have done. But when we can’t build a new fiber route or store data – say, when we need to get real-time packets from point to point over the existing network – yet another option might be to route packets more efficiently with sophisticated QoS technologies. Each of these solutions fits a particular situation. They take advantage of, or submit to, the technological and economic trade-offs of the moment or the era. They are all legitimate options. Policy simply must allow for the diversity and flexibility of technical and economic options – including paid prioritization – needed to manage networks and deliver value to end-users.

Depending on how far the FCC is willing to take these misguided restrictions, it could actually lead to the very outcomes most reviled by “open Internet” fanatics — that is, more industry concentration, more “walled gardens,” more closed networks. Here’s how I described the possible effect of restrictions on the important voluntary network management tools and business partnerships needed to deliver robust multimedia services:

There has also been discussion of an exemption for “specialized services.” Like wireless, it is important that such specialized services avoid the possible innovation-sapping effects of a Net Neutrality regulatory regime. But the Commission should consider several unintended consequences of moving down the path of explicitly defining, and then exempting, particular “specialized” services while choosing to regulate the so-called “basic,” “best-effort,” or “entry level” “open Internet.”

Regulating the “basic” Internet but not “specialized” services will surely push most of the network and application innovation and investment into the unregulated sphere. A “specialized” exemption, although far preferable to a Net Neutrality world without such an exemption, would tend to incentivize both CAS providers and ISPs service providers to target the “specialized” category and thus shrink the scope of the “open Internet.”

In fact, although specialized services should and will exist, they often will interact with or be based on the “basic” Internet. Finding demarcation lines will be difficult if not impossible. In a world of vast overlap, convergence, integration, and modularity, attempting to decide what is and is not “the Internet” is probably futile and counterproductive. The very genius of the Internet is its ability to connect to, absorb, accommodate, and spawn new networks, applications and services. In a great compliment to its virtues, the definition of the Internet is constantly changing. Moreover, a regime of rigid quarantine would not be good for consumers. If a CAS provider or ISP has to build a new physical or logical network, segregate services and software, or develop new products and marketing for a specifically defined “specialized” service, there would be a very large disincentive to develop and offer simple innovations and new services to customers over the regulated “basic” Internet. Perhaps a consumer does not want to spend the extra money to jump to the next tier of specialized service. Perhaps she only wants the service for a specific event or a brief period of time. Perhaps the CAS provider or ISP can far more economically offer a compelling service over the “basic” Internet with just a small technical tweak, where a leap to a full-blown specialized service would require more time and money, and push the service beyond the reach of the consumer. The transactions costs of imposing a “specialized” quarantine would reduce technical and economic flexibility on both CAS providers and ISPs and, most crucially, on consumers.

Or, as we wrote in our previous Reply Comments about a related circumstance, “A prohibition of the voluntary partnerships that are likely to add so much value to all sides of the market – service provider, content creator, and consumer – would incentivize the service provider to close greater portions of its networks to outside content, acquire more content for internal distribution, create more closely held ‘managed services’ that meet the standards of the government’s ‘exclusions,’ and build a new generation of larger, more exclusive ‘walled gardens’ than would otherwise be the case. The result would be to frustrate the objective of the proceeding. The result would be a less open Internet.”

It is thus possible that a policy seeking to maintain some pure notion of a basic “open Internet” could severely devalue the open Internet the Commission is seeking to preserve.

All this said, the FCC’s legal standing is so tenuous and this order so rooted in reasoning already rejected by the courts, I believe today’s Net Neutrality rule will be overturned. Thus despite the numerous substantive and procedural errors committed on this “darkest day of the year,” I still expect the Internet to “survive and thrive.”

The Internet Survives, and Thrives, For Now

See my analysis of the FCC’s new “net neutrality” policy at RealClearMarkets:

Despite the Federal Communications Commission’s “net neutrality” announcement this week, the American Internet economy is likely to survive and thrive. That’s because the new proposal offered by FCC chairman Julius Genachowski is lacking almost all the worst ideas considered over the last few years. No one has warned more persistently than I against the dangers of over-regulating the Internet in the name of “net neutrality.”

In a better world, policy makers would heed my friend Andy Kessler’s advice to shutter the FCC. But back on earth this new compromise should, for the near-term at least, cap Washington’s mischief in the digital realm.

. . .

The Level 3-Comcast clash showed what many of us have said all along: “net neutrality” was a purposely ill-defined catch-all for any grievance in the digital realm. No more. With the FCC offering some definition, however imperfect, businesses will now mostly have to slug it out in a dynamic and tumultuous technology arena, instead of running to the press and politicians.

Caveats. Already!

If it’s true, as Nick Schulz notes, that FCC Commissioner Copps and others really think Chairman Genachowski’s proposal today “is the beginning . . . not the end,” then all bets are off. The whole point is to relieve the overhanging regulatory threat so we can all move forward. More — much more, I suspect — to come . . . .

FCC Proposal Not Terrible. Internet Likely to Survive and Thrive.

The FCC appears to have taken the worst proposals for regulating the Internet off the table. This is good news for an already healthy sector. And given info-tech’s huge share of U.S. investment, it’s good news for the American economy as a whole, which needs all the help it can get.

In a speech this morning, FCC chair Julius Genachowski outlined a proposal he hopes the other commissioners will approve at their December 21 meeting. The proposal, which comes more than a year after the FCC issued its Notice of Proposed Rule Making into “Preserving the Open Internet,” appears mostly to codify the “Four Principles” that were agreed to by all parties five years ago. Namely:

- No blocking of lawful data, websites, applications, services, or attached devices.

- Transparency. Consumers should know what the services and policies of their providers are, and what they mean.

- A prohibition of “unreasonable discrimination,” which essentially means service providers must offer their products at similar rates and terms to similarly situated customers.

- Importantly, broadband providers can manage their networks and use new technologies to provide fast, robust services. Also, there appears to be even more flexibility for wireless networks, though we don’t yet know the details.

(All the broad-brush concepts outlined today will need closer scrutiny when detailed language is unveiled, and as with every government regulation, implementation and enforcement can always yield unpredictable results. One also must worry about precedent and a new platform for future regulation. Even if today’s proposal isn’t too harmful, does the new framework open a regulatory can of worms?)

So, what appears to be off the table? Most of the worst proposals that have been flying around over the last year, like . . .

- Reclassification of broadband as an old “telecom service” under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934, which could have pierced the no-government seal on the Internet in a very damaging way, unleashing all kinds of complex and antiquated rules on the modern Net.

- Price controls.

- Rigid nondiscrimination rules that would have barred important network technologies and business models.

- Bans of quality-of-service technologies and techniques (QoS), tiered pricing, or voluntary relationships between ISPs and content/application/service (CAS) providers.

- Open access mandates, requiring networks to share their assets.

Many of us have long questioned whether formal government action in this arena is necessary. The Internet ecosystem is healthy. It’s growing and generating an almost dizzying array of new products and services on diverse networks and devices. Communications networks are more open than ever. Facebook on your BlackBerry. Netflix on your iPad. Twitter on your TV. The oft-cited world broadband comparisons, which say the U.S. ranks 15h, or even 26th, are misleading. Those reports mostly measure household size, not broadband health. Using new data from Cisco, we estimate the U.S. generates and consumes more network traffic per user and per capita than any nation but South Korea. (Canada and the U.S. are about equal.) American Internet use is twice that of many nations we are told far outpace the U.S. in broadband. Heavy-handed regulation would have severely depressed investment and innovation in a vibrant industry. All for nothing.

Lots of smart lawyers doubt the FCC has the authority to issue even the relatively modest rules it outlined today. They’re probably right, and the question will no doubt be litigated (yet again), if Congress does not act first. But with Congress now divided politically, the case remains that Mr. Genachowski’s proposal is likely the near-term ceiling on regulation. Policy might get better than today’s proposal, but it’s not likely to get any worse. From what I see today, that’s a win for the Internet, and for the U.S. economy.

— Bret Swanson

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

The FCC’s apparent about-face on Net Neutrality is really perplexing.

Over the past few weeks it looked like the Administration had acknowledged economic reality (and bipartisan Capitol Hill criticism) and turned its focus to investment and jobs. Outgoing NEC Director Larry Summers and Commerce Secretary Gary Locke announced a vast expansion of available wireless spectrum, and FCC chairman Julius Genachowski used his speech to the NARUC state regulators to encourage innovation and employment. Gone were mentions of the old priorities — intrusive new regulations such as Net Neutrality and Title II reclassification of modern broadband as an old telecom service. Finally, it appeared, an already healthy and vibrant Internet sector could stop worrying about these big new government impositions — and years of likely litigation — and get on with building the 21st century digital infrastructure.

But then came word at the end of last week that the FCC would indeed go ahead with its new Net Neutrality regs. Perhaps even issuing them on December 22, just as Congress and the nation take off for Christmas vacation [the FCC now says it will hold its meeting on December 15]. When even a rare economic sunbeam is quickly clouded by yet more heavy-handedness from Washington, is it any wonder unemployment remains so high and growth so low?

Any number of people sympathetic to the economy’s and the Administration’s plight are trying to help. Last week David Leonhardt of the New York Times pointed the way, at least in a broad strategic sense: “One Way to Trim the Deficit: Cultivate Growth.” Yes, economic growth! Remember that old concept? Economist and innovation expert Michael Mandel has suggested a new concept of “countercyclical regulatory policy.” The idea is to lighten regulatory burdens to boost growth in slow times and then, later, when the economy is moving full-steam ahead, apply more oversight to curb excesses. Right now, we should be lightening burdens, Mandel says, not imposing new ones:

it’s really a dumb move to monkey with the vibrant and growing communications sector when the rest of the economy is so weak. It’s as if you have two cars — one running, one in the repair shop — and you decide it’s a good time to rebuild the transmission of the car that actually works because you hear a few squeaks.

Apparently, FCC honchos met with interested parties this morning to discuss what comes next. Unfortunately, at a time when we need real growth, strong growth, exuberant growth! (as Mandel would say), the Administration appears to be saddling an economy-lifting reform (wireless spectrum expansion) with leaden regulation. What’s the point of new wireless spectrum if you massively devalue it with Net Neutrality, open access, and/or Title II?

One step forward, two steps back (ten steps back?) is not an exuberant growth and jobs strategy.