The U.S. wireless sector has been only mildly regulated over the last decade. We’d argue this is a key reason for its success. But this presumption of mostly unfettered experimentation and dynamism may be changing.

Consider Sprint’s apparent decision to use “roaming” in Oklahoma and Kansas instead of building its own network. Now, roaming is a standard feature of mobile networks worldwide. Company A might not have as much capacity as it would like in some geography, so it pays company B, who does have capacity there, for access. Company A’s customers therefore get wider coverage, and Company B is paid for use of its network.

The problem comes with the FCC’s 2011 “digital roaming” order. Last spring three FCC commissioners decided that private mobile services — which the Communications Act says “shall not . . . be treated as a common carrier” — are a common carrier. Only D.C. lawyers smarter than you and me can figure out how to transfigure “shall not” into “may.” Anyway, the possible effect is to subject mobile data — one of the fastest growing sectors anywhere on earth — to all sorts of forced access mandates and price controls.

We warned here and here that turning competitive broadband infrastructure into a “common carrier” could discourage all players in the market from building more capacity and covering wider geographies. If company A can piggyback on company B’s network at below market rates, why would it build its own expensive network? And if company B’s network capacity is going to company A’s customers, instead of its own customers, do we think company B is likely to build yet more cell sites and purchase more spectrum?

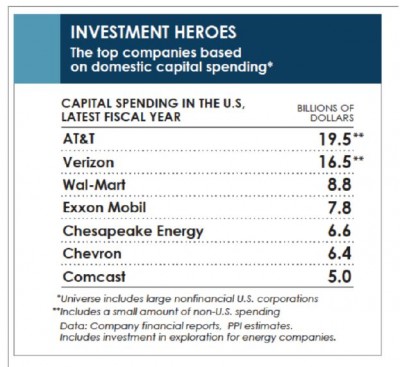

With 37 million iPhones and 15million iPads sold last quarter, we need more spectrum, more cell towers, more capacity. This isn’t the way to get it. And what we are seeing with Sprint’s decision to roam instead of build in Oklahoma and Kansas may be the tip of this anti-investment iceberg.

Last spring when the data roaming order came down we began wondering about a possible “slow walk to a reregulated communications market.” Among other items, we cited net neutrality, possible new price controls for Special Access links to cell sites, and a host of proposed regulations affecting things like behavioral advertising and intellectual property (see, PIPA/SOPA). Since then we’ve seen the government block the AT&T-T-Mobile merger. And the FCC is now holding up its own important push for more wireless spectrum because it wants the right to micromanage who gets what spectrum and how mobile carriers can use it.

Many of these items can be thoughtfully debated. But the number of new encroachments onto the communications sector threatens to slow its growth. Many of these encroachments, moreover, are taking place outside any basic legislative authority. In the digital roaming and net neutrality cases, for example, the FCC appeared clearly to grant itself extra- if not il-legal authority. These new regulations are now being challenged in court.

We need some restraint across the board on these matters. The Internet is too important. We can’t allow a quiet, gradual reregulation of the sector to slow down our chief engine of economic growth.

— Bret Swanson