What would “the New Normal” of a mere 1% per capita GDP growth mean for the American economy over the next few decades? What if it’s even worse, as many are now predicting? Is there anything we can do about it? If so, what? We address these items in our new article for the Business Horizon Quarterly — “Beyond the New Normal, a New Era of Growth.”

The $66-billion Internet Expansion

Sixty-six billion dollars over the next three years. That’s AT&T’s new infrastructure plan, announced yesterday. It’s a bold commitment to extend fiber optics and 4G wireless to most of the country and thus dramatically expand the key platform for growth in the modern U.S. economy.

The company specifically will boost its capital investments by an additional $14 billion over previous estimates. This should enable coverage of 300 million Americans (around 97% of the population) with LTE wireless and 75% of AT&T’s residential service area with fast IP broadband. It’s adding 10,000 new cell towers, a thousand distributed antenna systems, and 40,000 “small cells” that augment and extend the wireless network to, for example, heavily trafficked public spaces. Also planned are fiber optic connections to an additional 1 million businesses.

As the company expands its fiber optic and wireless networks — to drive and accommodate the type of growth seen in the chart above — it will be retiring parts of its hundred-year-old copper telephone network. To do this, it will need cooperation from federal and state regulators. This is the end of phone network, the transition to all Internet, all the time, everywhere.

This kind of “prosperity” isn’t good enough

Today, Princeton’s Alan Blinder says things are looking up, that we’re finally traveling the road to prosperity, albeit slowly. It’s a rather timid claim:

there are definitely positive signs. The stock market is near a five-year high. Recent data on consumer spending and confidence show improvement, though we need more data before declaring victory. At long last, the housing market is growing rapidly, albeit from a very low base . . . .

On balance, the U.S. economy is healing its wounds—that’s another fact. But none of this puts us on the verge of an exuberant boom. Still, if the fiscal cliff is avoided and the European debt crisis doesn’t explode in our face, both GDP growth and job growth should be higher in 2013 than in 2012—even under current policies. But that’s a forecast, not a fact.

Stanford’s John Taylor counters some of Blinder’s claims:

First, he admits that real GDP growth—the most comprehensive measure we have of the state of the economy—is declining; that’s not an improvement.

Second, he admits that, according to the payroll survey, job growth isn’t faster in 2012 than 2011; that’s not an improvement either.

Third, he mentions that the household survey shows employment growth is faster, but that growth must be measured relative to a growing population. If you look at the employment to population ratio, it is the same (58.5%) in the 12 month period starting in October 2009 (the month he chooses as the low point) as in the past 12 months. That’s not an improvement.

Fourth, he shows that the unemployment rate is coming down. But much of that improvement is due to the decline in the labor force participation rate as people drop out of the labor force. According to the CBO, unemployment would be 9 percent if that unusual and distressing decline–certainly not an improvement–had not occurred.

He then goes on to consider forecasts, saying that there are promising signs, such as the housing market. The problem here, however, is that growth is weakening even as housing is less of a drag, because other components of GDP are flagging.

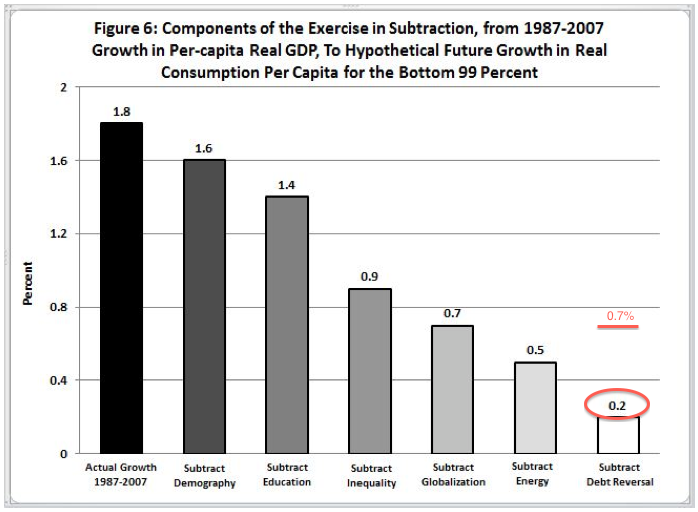

Meanwhile, there is Northwestern’s Bob Gordon, who is making a much stronger, longer term forecast — that the next several decades will be pretty awful. Specifically, that real U.S. economic growth is likely to halve — or worse — from its recent and historical trend of about 2% per-capita per-year.

We’ve been emphasizing just how important it is to get the economy moving again, and how important long term growth is for jobs, incomes, overall opportunity, and for governmental budgets. The Gordon scenario is even worse than the so-called New Normal of around 1% per-capita growth (or 2% overall growth). Gordon projects per-capita growth over the next few decades of around 0.7%. (In non-per-capita terms, the way GDP figures are most often reported, that’s about 1.7%). He thinks growth for the “99%” will be far worse — just 0.2% per-capita.

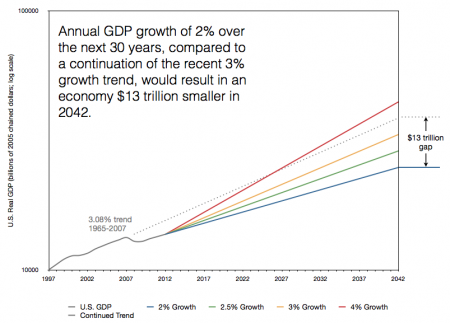

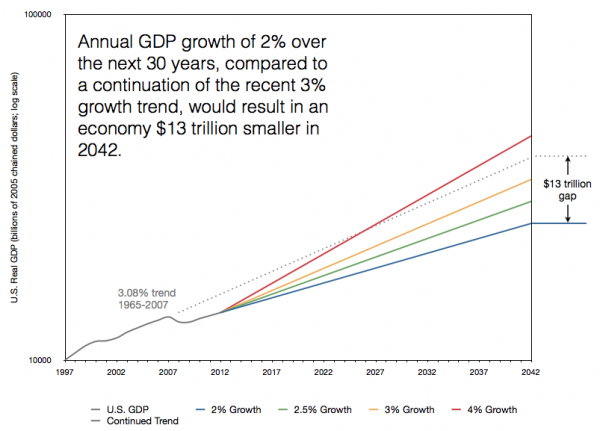

In the chart below, you can see just how devastating a New Normal scenario would be, let alone Gordon’s even more pessimistic projection. It’s urgent that we implement a sweeping new set pro-growth reforms on taxes, regulation, immigration, trade, education, and monetary policy.

Discussing Broadband Via Broadband

It was nice of Ball State University’s Digital Policy Institute (@DigitalPolicy) to include me last Friday in a webinar discussion on broadband policy. Joining the virtual discussion were Leslie Marx, of Duke and formerly FCC chief economist; Anna-Maria Kovacs, well-known regulatory analyst and fellow at Georgetown; and Michael Santorelli of New York Law School.

You can find a replay of the webinar here. Our broadband discussion, which begins at 1:55:48, was preceded by a good discussion of consumer online privacy, which you might also enjoy.

Flashback: “there is no inherent shortage of oil”

The energy boom is an apparent surprise to many. I don’t know why. Here’s the photo, caption, and story right now (Wednesday night) on the front page of The Wall Street Journal :

Here was our take in 2006:

there is no inherent shortage of oil. One tiny shale formation right in America’s backyard — the 1,200 square mile Piceance Basin of western Colorado — contains a trillion barrels, more than all the proven reserves in the world. Vast open spaces across the globe remain unexplored or untapped.

Today, it’s Dakota, Texas, and Pennsylvania shale that is leading the new boom. As a few smart guys wrote, we have a “bottomless well” of energy, if only we allow ourselves to find, refine, and innovate.

A Policy Path to Internet 2020

Life’s only certainty is change. Nowhere more true than with modern technologies, particularly broadband. Problem is, lots of government rules are not coming along for the ride.

Yesterday the Communications Liberty and Innovation Project (CLIP) hosted regulatory experts to discuss ways the FCC might incent more investment in digital infrastructure.

A fresh voice at the FCC is focusing the agency and the country on such a policy path of abundant wired and wireless broadband. New FCC Commissioner Ajit Pai (@AjitPaiFCC) yesterday called for the creation of an IP Transition Task Force as a way to accelerate the transition from analog networks to faster and more ubiquitous digital networks. Network providers, he said, want to know how IP services will be regulated before making major infrastructure investments. Commissioner Pai also discussed economic growth and job creation, asserting every $1 billion spent on fiber deployment creates between 15,000 and 20,000 jobs. Therefore to pave the way for robust private sector investment in the IP infrastructure, the FCC must signal a clear intention not to apply outdated 20th century regulations to these 21st century technologies.

The follow-up discussion focused on the need for a regulatory framework that will promote competition and economic growth while also maximizing consumer benefits. Jonathan Banks of US Telecom pointed out that the telecommunications industry is investing $65 billion per year, every year, in broadband infrastructure — a huge boost to current and future economic growth. Whoever occupies the White House after November should make it clear that expanding the nation’s “infostructure” with private investment dollars is a key national priority that will generate huge dividends — digital and otherwise.

Anemic Growth and Why Only Non-Fed Policy Can Boost It

The central economic problem — one that exacerbates all our other serious challenges, from debt to entitlements to persistently low employment — is a sluggish rate of economic growth. Worse than sluggish, really. At less than 2% per annum real growth, the economy is barely limping along. We are growing at perhaps just a third or a fourth the speed (or worse!) compared to previous recoveries from recessions of similar severity.

One school of thought, however, says that there’s not much we can do about it. The nature of the panic — with housing and financial institutions at its core — makes stagnation all but certain. Nonsense, says John Taylor of Stanford, in this new video (part 2 of 3) hosted by the Hoover Institution’s Russ Roberts:

In the next video, Yale’s Robert Shiller reinforces the point about housing. The author of the Case-Shiller Home Price Index questions whether the Fed can reflate home prices with “one button” and whether its zero-rates-forever policy might not do more harm than good. It’s more about “animal spirits,” Shiller says, which means housing is more a function of economic growth than growth is a function of housing.

Possible progress on spectrum expansion

For years we’ve been highlighting the need for policies that encourage communications infrastructure investment. Fiber, cell towers, data centers — these are the foundation of our growing digital economy, the tools of which are increasingly integral components of every business in every industry. One of the most crucial inputs that makes the digital economy go, however, is invisible. It’s wireless spectrum, and today we don’t have the right spectrum allocation to ensure continued wireless growth and innovation.

So it was good news to hear that former FCC commissioner Jonathan Adelstein is the new CEO of the Personal Communications Industry Association, also known as the “Wireless Infrastructure Association.” The companies he will represent are the mobile service providers, cell tower operators, and associated service companies that build these often unseen networks.

“The ultimate goal for consumers and the economy is to accommodate the need for more wireless data,” Adelstein told Communications Daily. “More spectrum is sort of the effective means for getting there . . . As more spectrum comes online it will ultimately require new infrastructure to accomplish the goal of meeting the data crunch.”

This gives a boost to the prospects for better spectrum policy.

Money, Inflation, the Euro – Most of What You Hear Is Wrong

Here’s a good interview with Chicago’s John Cochrane, who offers incisive contrarian views on money, inflation, “stimulus,” Greece, the euro, economic growth, and Milton Friedman’s “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” meme. I wrote about these topics here.

The Growth Effect on Jobs

Is the persistently high unemployment rate a secular, rather than cyclical, occurrence? Is it, in other words, a basic shift in the labor market that will leave us with semi-permanently higher joblessness for years or decades to come — no matter what we try to do about it?

Ed Lazear of Stanford and James Spletzer of the U.S. Census Bureau dug into the matter and presented their findings over the weekend at the Fed’s Jackson Hole economic gathering. Lazear also summarized the research in The Wall Street Journal. “The unemployment rate has exceeded 8% for more than three years,” wrote Lazear.

This has led some commentators and policy makers to speculate that there has been a fundamental change in the labor market. The view is that today’s economy cannot support unemployment rates below 5%—like the levels that prevailed before the recession and in the late 1990s. Those in government may take some comfort in this view. It lowers expectations and provides a rationale for the dismal labor market.

Lazear and Spletzer looked at what happened in particular industries and specific jobs, asking whether the real problem is that some industries are too old and aren’t coming back and whether there is substantial “mismatch” between job requirements and worker skills that prevent jobs from being filled. No doubt the economy is always changing, and few industries or jobs stay the same forever, but they found, for example, that

mismatch increased dramatically from 2007 to 2009. But just as rapidly, it decreased from 2009 to 2012. Like unemployment itself, industrial mismatch rises during recessions and falls as the economy recovers. The measure of mismatch that we use, which is an index of how far out of balance are supply and demand, is already back to 2005 levels.

Whatever mismatch exists today was also present when the labor market was booming. Turning construction workers into nurses might help a little, because some of the shortages in health and other industries are a long-run problem. But high unemployment today is not a result of the job openings being where the appropriately skilled workers are unavailable.

Lazear and Spletzer concluded that no, the jobless problem is not mostly secular, and we shouldn’t accept high unemployment.

The reason for the high level of unemployment is the obvious one: Overall economic growth has been very slow. Since the recession formally ended in June 2009, the economy has grown at 2.2% per year, or 6.6% in total. An empirical rule of thumb is that each percentage point of growth contributes about one-half a percentage point to employment.

The economy has regained about four million jobs since bottoming out in early 2010, which is right around 3% of employment—just the gain that would be predicted from past experience. Things aren’t great, but the failure is a result of weak economic growth, not of a labor market that is not in sync with the rest of the economy.

The evidence suggests that to reduce unemployment, all we need to do is grow the economy. Unfortunately, current policies aren’t doing that. The problems in the economy are not structural and this is not a jobless recovery. A more accurate view is that it is not a recovery at all.

The upside of this dismal situation is that we can do something about it. Think about what a different set of pro-growth policies could mean for American workers. Using Lazear’s very rough rule of “one point growth, half a point employment,” we can get an idea of what faster growth might yield in the labor market.

At today’s feeble 2% growth rate, we might expect to add several tens of thousands, or maybe a hundred thousand or two, of jobs each month. Over the next five years, at 2%, we might add something like seven million jobs. But that’s barely enough to keep up with population growth. Three percent growth, the historic average, meanwhile, would likely yield around 10 million net new jobs, 3 million more than at today’s 2% growth rate.

But three percent growth coming out of a deep recession and slow recovery is itself slower-than-usual recovery speed. It is certainly not an ambitious objective. Coming out of a slump like today’s we should be able to grow at 4, 5, or 6% for several years, as we did in the mid-1980s. Four percent growth for the next five years could add 14 million net new jobs, and 5% growth could add 17.5 million — meaning in 2017 something approaching 11 million more Americans would be working compared to today’s sclerotic 2% growth.

Keep in mind, these are rough rules of thumb, not forecasts or projections, and we’re leaving out lots of technical dynamics. There’s a lot going on in an economy, and we do not pretend these are precise estimates. The point is to show the magnitudes involved — that faster growth can provide jobs for millions more Americans in a relatively short period of time.

The problem is that U.S. policy before and after the financial panic and recession has not supported growth — I’d argue it has impeded growth. Faster growth is so important, we should be doing everything possible to enact policies that encourage it — or, if we can’t enact them today, then at least pointing the nation in the right direction.

A more efficient tax code that rewards rather than punishes investment and entrepreneurship would make a huge difference. Unfortunately, some in Washington and the states are proposing higher tax rates and new carve-outs and favors that will make real tax reform impossible. We need to ensure that Washington doesn’t keep consuming an ever greater share of the economy. But again, we’ve just seen a huge jump in the government-economy ratio, from 20% to 25%, and the current budget path just makes this ratio worse and worse over time.

Does anyone believe we have a regulatory system that promotes economic growth? In each of the last two years, the Federal Register of government regulations has grown by more than 81,000 pages. We’ve recently seen Washington drape vast new blankets of regulation over finance and health care and interfere at every turn with our energy economy — a sector that is poised to deliver explosive growth in coming years. Other regulatory actions, like FCC interference in broadband and mobile networks, can slow growth at the margins or, depending on how zealous regulators choose to be, severely disrupt an innovation ecosystem.

The economy is too complex to dial up exactly what we want. I am not suggesting a simple flip of a switch can achieve this dramatic improvement. But we should be giving ourselves — and American citizens — as many chances as possible. Given what’s at stake, there’s no excuse for not lining up policy to maximize the opportunities for faster growth.

FCC’s 706 Broadband Report Does Not Compute

Yesterday the Federal Communications Commission issued 181 pages of metrics demonstrating, to any fair reader, the continuing rapid rise of the U.S. broadband economy — and then concluded, naturally, that “broadband is not yet being deployed to all Americans in a reasonable and timely fashion.” A computer, being fed the data and the conclusion, would, unable to process the logical contradictions, crash.

Yesterday the Federal Communications Commission issued 181 pages of metrics demonstrating, to any fair reader, the continuing rapid rise of the U.S. broadband economy — and then concluded, naturally, that “broadband is not yet being deployed to all Americans in a reasonable and timely fashion.” A computer, being fed the data and the conclusion, would, unable to process the logical contradictions, crash.

The report is a response to section 706(b) of the 1996 Telecom Act that asks the FCC to report annually whether broadband “is being deployed . . . in a reasonable and timely fashion.” From 1999 to 2008, the FCC concluded that yes, it was. But now, as more Americans than ever have broadband and use it to an often maniacal extent, the FCC has concluded for the third year in a row that no, broadband deployment is not “reasonable and timely.”

The FCC finds that 19 million Americans, mostly in very rural areas, don’t have access to fixed line terrestrial broadband. But Congress specifically asked the FCC to analyze broadband deployment using “any technology.”

“Any technology” includes DSL, cable modems, fiber-to-the-x, satellite, and of course fixed wireless and mobile. If we include wireless broadband, the unserved number falls to 5.5 million from the FCC’s headline 19 million. Five and a half million is 1.74% of the U.S. population. Not exactly a headline-grabbing figure.

Even if we stipulate the FCC’s framework, data, and analysis, we’re still left with the FCC’s own admission that between June 2010 and June 2011, an additional 7.4 million Americans gained access to fixed broadband service. That dropped the portion of Americans without access to 6% in 2011 from around 8.55% in 2010 — a 30% drop in the unserved population in one year. Most Americans have had broadband for many years, and the rate of deployment will necessarily slow toward the tail-end of any build-out. When most American households are served, there just aren’t very many to go, and those that have yet to gain access are likely to be in the very most difficult to serve areas (e.g. “on tops of mountains in the middle of nowhere”). The fact that we still added 7.4 million broadband in the last year, lowering the unserved population by 30%, even using the FCC’s faulty framework, demonstrates in any rational world that broadband “is being deployed” in a “reasonable and timely fashion.”

But this is not the rational world — it’s D.C. in the perpetual political silly season.

One might conclude that because the vast majority of these unserved Americans live in very rural areas — Alaska, Montana, West Virginia — the FCC would, if anything, suggest policies tailored to boost infrastructure investment in these hard-to-reach geographies. We could debate whether these are sound investments and whether the government would do a good job expanding access, but if rural deployment is a problem, then presumably policy should attempt to target and remediate the rural underserved. Commissioner McDowell, however, knows the real impetus for the FCC’s tortured no-confidence vote — its regulatory agenda.

McDowell notes that the report repeatedly mentions the FCC’s net neutrality rules (now being contested in court), which are as far from a pro-broadband policy, let alone a targeted one, as you could imagine. If anything, net neutrality is an impediment to broader, faster, better broadband. But the FCC is using its thumbs-down on broadband deployment to prop up its intrusions into a healthy industry. As McDowell concluded, “the majority has used this process as an opportunity to create a pretext to justify more regulation.”

The $3 trillion opportunity for 2022

There’s more to life than economics, but almost nothing matters more to more people than the rate of long-term economic growth. It completely changes the life possibilities for individuals and families and determines the prospects of nations. It also happens to be the central factor in governmental budgets.

We’ve been saying for the last few years that growth is our biggest problem — but also our biggest opportunity. Faster growth would not only put Americans back to work but also help resolve budget impasses and assist in the long-overdue transformations of our entitlement programs. The current recovery, however, is worse than mediocre. It is dangerously feeble. With every passing day, we fall further behind. Investments aren’t made. Risks aren’t taken. Business ideas are shelved. Joblessness persists, and millions of Americans drop out of the labor force altogether. Continued stagnation would of course exacerbate an already dire long-term unemployment problem. It would also, however, turn America’s unattractive habitual overspending into a possible catastrophe of debt.

John Cochrane of the University of Chicago shows, in the chart below, just how far we’ve slipped from our historical growth path. The red line is the 1965-2007 trend line growth of 3.07%, and the thin black line shows the recession and weak recovery.

Recessions are of course downward deviations from a trend line of growth. Trendlines, however, include recessions, and recoveries thus usually exhibit faster-than-trend growth that catches up to trend. To be sure, trends may not continue forever. Historical performance, as they say, is not a guarantee of future results. Perhaps structural factors in the U.S. and world economies have lowered our “potential” growth rate. This possibility is shown in the blue “CBO Potential” line, which depicts the “new normal” of diminished expectations. Yet the current recovery cannot even catch up to this anemic trend line, which supposedly reflects the downgraded potential of the U.S. economy.

Here is another way to visualize today’s stagnation, from Scott Grannis:

Economies are built on expectations. If the “new normal” of 2.35% growth is correct, then we’ve got problems. All our individual, family, business, and government plans will have to downshift. If growth is even lower than that, tomorrow’s problems will tower over today’s. If, on the other hand, we can reignite the American growth engine, then we’ve got a shot to not only reverse today’s decline but also to open the door to a new era of renewed optimism and, yes, rising expectations.

Faster compounding growth over time makes all the difference. One new paper shows how, with a fundamentally new policy direction on taxes and regulation, real GDP in the U.S. could be “between $2.1 and $3.1 trillion higher in 2022 than it would be under a continuation of current slow growth.” Think of that — an American economy perhaps trillions of dollars larger in a single year a decade from now, with better pro-growth policies. That’s a lot of jobs, a lot of higher incomes, a lot of new businesses, and — whether your preference is more or less government spending — much healthier government budgets . . . summed up in one last chart.

Misunderstanding the Mobile Ecosystem

Mobile communications and computing are among the most innovative and competitive markets in the world. They have created a new world of software and offer dramatic opportunities to improve productivity and creativity across the industrial spectrum.

Last week we published a tech note documenting the rapid growth of mobile and the importance of expanding wireless spectrum availability. More clean spectrum is necessary both to accommodate fast-rising demand and drive future innovations. Expanding spectrum availability might seem uncontroversial. In the report, however, we noted that one obstacle to expanding spectrum availability has been a cramped notion of what constitutes competition in the Internet era. As we wrote:

Opponents of open spectrum auctions and flexible secondary markets often ignore falling prices, expanding choices, and new features available to consumers. Instead they sometimes seek to limit new spectrum availability, or micromanage its allocation or deployment characteristics, charging that a few companies are set to dominate the market. Although the FCC found that 77% of the U.S. population has access to three or more 3G wireless providers, charges of a coming “duopoly” are now common.

This view, however, relies on the old analysis of static utility or commodity markets and ignores the new realities of broadband communications. The new landscape is one of overlapping competitors with overlapping products and services, multi-sided markets, network effects, rapid innovation, falling prices, and unpredictability.

Sure enough, yesterday Sprint CEO Dan Hesse made the duopoly charge and helped show why getting spectrum policy right has been so difficult.

Q: You were a vocal opponent of the AT&T/T-Mobile merger. Are you satisfied you can compete now that the merger did not go through?

A: We’re certainly working very hard. There’s no question that the industry does have an issue with the size of the duopoly of AT&T and Verizon. I believe that over time we’ll see more consolidation in the industry outside of the big two, because the gap in size between two and three is so enormous. Consolidation is healthy for the industry as long as it’s not AT&T and Verizon getting larger.

Hesse goes even further.

Hesse also seemed to be likening Sprint’s struggles in competing with AT&T-Rex and Big Red as a fight against good and evil. Sprint wants to wear the white hat, according to Hesse. “At Sprint, we describe it internally as being the good guys, of doing the right thing,” he said.

This type of thinking is always a danger if you’re trying to make sound policy. Picking winners and losers is inevitably — at best — an arbitrary exercise. Doing so based on some notion of corporate morality is plain silly, but even more reasonable sounding metrics and arguments — like those based on market share — are often just as misleading and harmful.

The mobile Internet ecosystem is growing so fast and changing with such rapidity and unpredictability that making policy based on static and narrow market definitions will likely yield poor policy. As we noted in our report:

It is, for example, worth emphasizing: Google and Apple were not in this business just a few short years ago.

Yet by the fourth quarter of 2011 Apple could boast an amazing 75% of the handset market’s profits. Apple’s iPhone business, it was widely noted after Apple’s historic 2011, is larger than all of Microsoft. In fact, Apple’s non-iPhone products are also larger than Microsoft.

Android, the mobile operating system of Google, has been growing even faster than Apple’s iOS. In December 2011, Google was activating 700,000 Android devices a day, and now, in the summer of 2012, it estimates 900,000 activations per day. From a nearly zero share at the beginning of 2009, Android today boasts roughly a 55% share of the global smartphone OS market.

. . .

Apple’s iPhone changed the structure of the industry in several ways, not least the relationships between mobile service providers and handset makers. Mobile operators used to tell handset makers what to make, how to make it, and what software and firmware could be loaded on it. They would then slap their own brand label on someone else’s phone.

Apple’s quick rise to mobile dominance has been matched by Blackberry maker Research In Motion’s fall. RIM dominated the 2000s with its email software, its qwerty keyboard, and its popularity with enterprise IT departments. But it couldn’t match Apple’s or Android’s general purpose computing platforms, with user-friendly operating systems, large, bright touch-screens, and creative and diverse app communities.

Sprinkled among these developments were the rise, fall, and resurgence of Motorola, and then its sale to Google; the rise and fall of Palm; the rise of HTC; and the decline of once dominant Nokia.

Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and others are building cloud ecosystems, sometimes complemented with consumer devices, often tied to Web apps and services, multimedia content, and retail stores. Many of these products and services compete with each other, but they also compete with broadband service providers. Some of these business models rely primarily on hardware, some software, some subscriptions, some advertising. Each of the companies listed above — a computer company, a search company, an ecommerce company, and a software company — are now major Internet infrastructure companies.

As Jeffrey Eisenach concluded in a pathbreaking analysis of the digital ecosystem (“Theories of Broadband Competition”), there may be market concentration in one (or more) layer(s) of the industry (broadly considered), yet prices are falling, access is expanding, products are proliferating, and innovation is as rapid as in any market we know.

The Who-What-Where-Why-How of Economic Growth

In all the recent debates over deficits, debt, unemployment, entitlements, bond markets, the euro, housing, etc., the absolutely central factor has too often been ignored. A new book, however, deals with nothing but this central factor — economic growth. If we’re going to improve the economic discussion, and the economy itself, The 4% Solution: Unleashing the Economic Growth America Needs is likely to serve as a good foundation.

The book contains chapters by five Nobel economists, including the modern dean of economic growth Robert Lucas, Ed Prescott on marginal tax rates, and Myron Scholes on true innovation; also Bob Litan on “home run” start-up firms, Nick Schulz on intangible assets, David Malpass on monetary policy, and others on entrepreneurs, immigration, debt, and budgets.

I’ve only skimmed many of the chapters, but one thing that jumped out is an important point about the links, and distinctions, between supply and demand. When economic growth has been discussed these last few years, the cause/cure usually cited is a drop in aggregate demand and the “stimulus” measures needed to boost it. It’s of course true that the housing bust and banking troubles caused lots of deleveraging and that government spending and interest rate cuts may help tide over certain consumers and businesses during temporary tough times. Despite substantial Keynesian fiscal and monetary “stimulus,” however — wild deficit spending, four years of zero-interest-rates, and a tripling of the Fed’s balance sheet — businesses, consumers, and the economy-at-large have not responded as hoped. Even if you believe in the efficacy of short term Keynesian growth policies, you ignore at great forecasting peril the array of countervailing anti-growth policies.

Here is how I put it in a Forbes online column last December:

the real problem with demand is supply. Consumption is partly based on current income and needs, sure, but more importantly it is a function of the expected future. Milton Friedman’s version of this idea was the permanent income hypothesis. More generally, we might ask, what are the prospects for prosperity?

We live in a complex, uncertain world. But it’s not unreasonable to believe, even after the Great Recession, that America and the globe still have prodigious potential to create new wealth. It’s also not unreasonable to believe that Washington has severely impaired America’s innovative capacity and our ability to grow.

If you think ObamaCare reinforces and expands many of the worst features of our overpriced, government-heavy health system, then you worry we might not get the productivity revolution we need in one of the largest sectors of our economy. If you think Dodd-Frank and other post-crisis ideas will discourage true financial innovation while preserving “too big to fail,” then you worry more financial disruptions are in store. If you think tax rates on capital and entrepreneurship are going up, then you might downgrade your estimates of the amount of investment and dynamism — and thus good jobs — America will enjoy.

A downgrade of expected long term growth impairs growth today.

In the new book, Lucas makes a similar argument:

imagine that households and businesses were somehow convinced that the United States would soon move toward a European-level welfare state, financed by a European tax structure. These beliefs would naturally be translated into beliefs that labor costs would soon increase and returns on investment decrease. Beliefs of a future GDP reduction of 30% would be brought forward into the present even before these beliefs could be realized (or refuted).

This is just hypothetical, of course, but it is a hypothesis that is entirely consistent with the way that we know economies work, everyone basing current decisions on expectations about future returns. What I have called recovery growth has happened after previous U.S. recessions and depressions and is certainly a worthy and attainable objective for economic policy today, but it would be foolish to take it as a foregone conclusion.

In the next chapter, Ed Prescott reinforces the point:

what people expect policies to be in the future determines what happens now. Bad policies can and often do depress the economy even before they are implemented. Peoples actions now depend on what they think policy will be — not what it was.

. . .

The disturbing fact is that, as of the beginning of 2012, the economy has not even partially recovered from the this recession. When it will recover is a political question and not an economic question. Only if the Americans making personal economic decisions knew what future policy would be could economists predict when recovery would occur.

This is one reason long term growth policies are often more important, even in the short term, than most short term “growth” policies.

The Real Deal on U.S. Broadband

Is American broadband broken?

Tim Lee thinks so. Where he once leaned against intervention in the broadband marketplace, Lee says four things are leading him to rethink and tilt toward more government control.

First, Lee cites the “voluminous” 2009 Berkman Report. Which is surprising. The report published by Harvard’s Berkman Center may have been voluminous, but it lacked accuracy in its details and persuasiveness in its big-picture take-aways. Berkman used every trick in the book to claim “open access” regulation around the world boosted other nation’s broadband economies and lack of such regulation in the U.S. harmed ours. But the report’s data and methodology were so thoroughly discredited (especially in two detailed reports issued by economists Robert Crandall, Everett Ehrlich, and Jeff Eisenach and Robert Hahn) that the FCC, which commissioned the report, essentially abandoned it. Here was my summary of the economists’ critiques:

The [Berkman] report botched its chief statistical model in half a dozen ways. It used loads of questionable data. It didn’t account for the unique market structure of U.S. broadband. It reversed the arrow of time in its country case studies. It ignored the high-profile history of open access regulation in the U.S. It didn’t conduct the literature review the FCC asked for. It excommunicated Switzerland.

. . .

Berkman’s qualitative analysis was, if possible, just as misleading. It passed along faulty data on broadband speeds and prices. It asserted South Korea’s broadband boom was due to open access regulation, but in fact most of South Korea’s surge happened before it instituted any regulation. The study said Japanese broadband, likewise, is a winner because of regulation. But regulated DSL is declining fast even as facilities-based (unshared, proprietary) fiber-to-the-home is surging.

Berkman also enjoyed comparing broadband speeds of tiny European and Asian countries to the whole U.S. But if we examine individual American states — New York or Arizona, for example — we find many of them outrank most European nations and Europe as a whole. In fact, applying the same Speedtest.com data Berkman used, the U.S. as a whole outpaces Europe as a whole! Comparing small islands of excellence to much larger, more diverse populations or geographies is bound to skew your analysis.

The Berkman report twisted itself in pretzels trying to paint a miserable picture of the U.S. Internet economy and a glowing picture of heavy regulation in foreign nations. Berkman, however, ignored the prima facie evidence of a vibrant U.S. broadband marketplace, manifest in the boom in Web video, mobile devices, the App Economy, cloud computing, and on and on.

How could the bulk of the world’s best broadband apps, services, and sites be developed and achieve their highest successes in the U.S. if American broadband were so slow and thinly deployed? We came up with a metric that seemed to refute the notion that U.S. broadband was lagging, namely, how much network traffic Americans generate vis-à-vis the rest of the world. It turned out the U.S. generates more network traffic per capita and per Internet user than any nation but South Korea and generates about two-thirds more per-user traffic than the closest advanced economy of comparable size, Western Europe.

Berkman based its conclusions almost solely on (incorrect) measures of “broadband penetration” — the number of broadband subscriptions per capita — but that metric turned out to be a better indicator of household size than broadband health. Lee acknowledges the faulty analysis but still assumes “broadband penetration” is the sine qua non measure of Internet health. Maybe we’re not awful, as Berkman claimed, Lee seems to be saying, but even if we correct for their methodological mistakes, U.S. broadband penetration is still just OK. “That matters,” Lee writes,

because a key argument for America’s relatively hands-off approach to broadband regulation has been that giving incumbents free rein would give them incentive to invest more in their networks. The United States is practically the only country to pursue this policy, so if the incentive argument was right, its advocates should have been able to point to statistics showing we’re doing much better than the rest of the world. Instead, the argument has been over just how close to the middle of the pack we are.

No, I don’t agree that the argument has consisted of bickering over whether the U.S. is more or less mediocre. Not at all. I do agree that advocates of government regulation have had to adjust their argument — U.S. broadband is awful mediocre. Yet they still hang their hat on “broadband penetration” because most other evidence on the health of the U.S. digital economy is even less supportive of their case.

In each of the last seven years, U.S. broadband providers have invested between $60 and $70 billion in their networks. Overall, the U.S. leads the world in info-tech investment — totaling nearly $500 billion last year. The U.S. now boasts more than 80 million residential broadband links and 200+ million mobile broadband subscribers. U.S. mobile operators have deployed more 4G mobile network capacity than anyone, and Verizon just announced its FiOS fiber service will offer 300 megabit-per-second residential connections — perhaps the fastest large-scale deployment in the world.

Eisenach and Crandall followed up their critique of the Berkman study with a fresh March 2012 analysis of “open access” regulation around the world (this time with Allan Ingraham). They found:

- “it is clear that copper loop unbundling did not accelerate the deployment or increase the penetration of first-generation broadband networks, and that it had a depressing effect on network investment”

- “By contrast, it seems clear that platform competition was very important in promoting broadband deployment and uptake in the earlier era of DSL and cable modem competition.”

- “to the extent new fiber networks are being deployed in Europe, they are largely being deployed by unregulated, non-ILEC carriers, not by the regulated incumbent telecom companies, and not by entrants that have relied on copper-loop unbundling.”

Lee doesn’t mention the incisive criticisms of the Berkman study nor the voluminous literature, including this latest example, showing open access policies are ineffective at best, and more likely harmful.

In coming posts, I’ll address Lee’s three other worries.

— Bret Swanson

New iPad, Fellow Bandwidth Monsters Hungry for More Spectrum

Last week Apple unveiled its third-generation iPad. Yesterday the company said the LTE versions of the device, which can connect via Verizon and AT&T mobile broadband networks, are sold out.

Last week Apple unveiled its third-generation iPad. Yesterday the company said the LTE versions of the device, which can connect via Verizon and AT&T mobile broadband networks, are sold out.

It took 15 years for laptops to reach 50 million units sold in a year. It took smartphones seven years. For tablets (not including Microsoft’s clunky attempt a decade ago), just two years. Mobile device volumes are astounding. In each of the last five years, global mobile phone sales topped a billion units. Last year smartphones outsold PCs for the first time – 488 million versus 432 million. This year well over 500 million smartphones and perhaps 100 million tablets could be sold.

Smartphones and tablets represent the first fundamentally new consumer computing platforms since the PC, which arrived in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Unlike mere mobile phones, they’ve got serious processing power inside. But their game-changing potency is really based on their capacity to communicate via the Internet. And this power is, of course, dependent on the cloud infrastructure and wireless networks.

But are wireless networks today prepared for this new surge of bandwidth-hungry mobile devices? Probably not. When we started to build 3G mobile networks in the middle of last decade, many thought it was a huge waste. Mobile phones were used for talking, and some texting. They had small low-res screens and were terrible at browsing the Web. What in the world would we do with all this new wireless capacity? Then the iPhone came, and, boom — in big cities we went from laughable overcapacity to severe shortage seemingly overnight. The iPhone’s brilliant screen, its real Web browsing experience, and the world of apps it helped us discover totally changed the game. Wi-Fi helped supply the burgeoning iPhone with bandwidth, and Wi-Fi will continue to grow and play an important role. Yet Credit Suisse, in a 2011 survey of the industry, found that mobile networks overall were running at 80% of capacity and that many network nodes were tapped out.

Today, we are still expanding 3G networks and launching 4G in most cities. Verizon says it offers 4G LTE in 196 cities, while AT&T says it offers 4G LTE in 28 markets (and combined with its HSPA+ networks offers 4G-like speeds to 200 million people in the U.S.). Lots of things affect how fast we can build new networks — from cell site permitting to the fact that these things are expensive ($20 billion worth of wireless infrastructure in the U.S. last year). But another limiting factor is spectrum availability.

Do we have enough radio waves to efficiently and cost-effectively serve these hundreds of millions of increasingly powerful mobile devices, which generate and consume increasingly rich content, with ever more stringent latency requirements, and which depend upon robust access to cloud storage and computing resources?

Capacity is a function of money, network nodes, technology, and radio waves. But spectrum is grossly misallocated. The U.S. government owns 61% of the best airwaves, while mobile broadband providers — where all the action is — own just 10%. Another portion is controlled by the old TV broadcasters, where much of this beachfront spectrum lay fallow or underused.

They key is allowing spectrum to flow to its most valuable uses. Last month Congress finally authorized the FCC to conduct incentive auctions to free up some unused and underused TV spectrum. Good news. But other recent developments discourage us from too much optimism on this front.

In December the FCC and Justice Department vetoed AT&T’s attempt to augment its spectrum and cell-site position via merger with T-Mobile. Now the FCC and DoJ are questioning Verizon’s announced purchase of Spectrum Co. — valuable but unused spectrum owned by a consortium of cable TV companies. The FCC has also threatened to tilt any spectrum auctions so that it decides who can bid, how much bidders can buy, and what buyers may or may not do with their spectrum — pretending Washington knows exactly how this fast-changing industry should be structured, thus reducing the value of spectrum and probably delaying availability of new spectrum and possibly reducing the sector’s pace of innovation.

It’s very difficult to see how it’s at all productive for the government to block companies who desperately need more spectrum from buying it from those who don’t want it, don’t need it, or can’t make good use of it. The big argument against AT&T and Verizon’s attempted spectrum purchases is “competition.” But T-Mobile wanted to sell to AT&T because it admitted it didn’t have the financial (or spectrum) wherewithal to build a super expensive 4G network. Apparently the same for the cable companies, who chose to sell to Verizon. Last week Dish Network took another step toward entering the 4G market with the FCC’s approval of spectrum transfers from two defunct companies, TerreStar and DBSD.

Some people say the proliferation of Wi-Fi or the increased use of new wireless technologies that economize on spectrum will make more spectrum availability unnecessary. I agree Wi-Fi is terrific and will keep growing and that software radios, cognitive radios, mesh networks and all the other great technologies that increase the flexibility and power of wireless will make big inroads. So fine, let’s stipulate that perhaps these very real complements will reduce the need for more spectrum at the margin. Then the joke is on the big companies that want to overpay for unnecessary spectrum. We still allow big, rich companies to make mistakes, right? Why, then, do proponents of these complementary technologies still oppose allowing spectrum to flow to its highest use?

Free spectrum auctions would allow lots of companies to access spectrum — upstarts, middle tier, and yes, the big boys, who desperately need more capacity to serve the new iPad.

— Bret Swanson

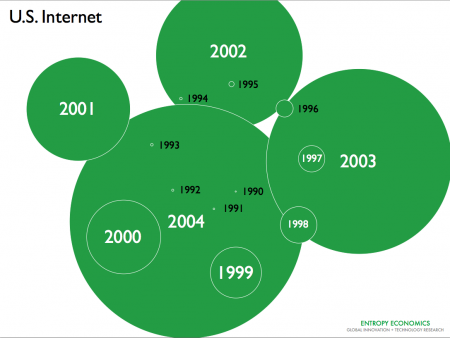

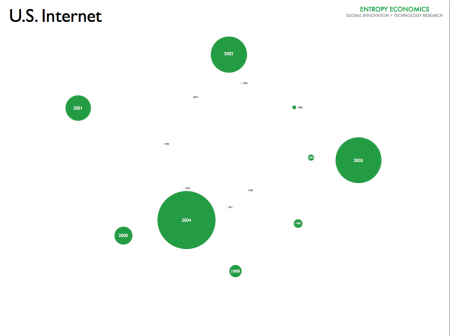

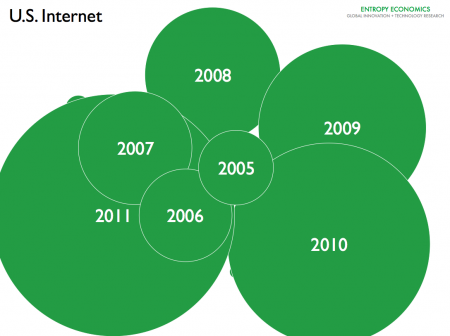

U.S. Internet Growth – Another Way to Visualize

We’ve published a lot of linear and log-scale line charts of Internet traffic growth. Here’s just another way to visualize what’s been happening since 1990. The first image shows 1990-2004.

The second image scales down the first to make room for the next period.

The third image, using the same scale as image 2, shows 2005-2011.

These images use data compiled by MINTS, with our own further analysis and estimations. Other estimates from Cisco and Arbor/Labovitz — and our own analysis based on those studies — show even higher traffic levels, though roughly similar growth rates.

Prof. Krugman misses the App Economy

Steve Jobs designed great products. It’s very, very hard to make the case that he created large numbers of jobs in this country.

— Prof. Paul Krugman, New York Times, January 25, 2012

Turns out, not very hard at all.

The App Economy now is responsible for roughly 466,000 jobs in the United States, up from zero in 2007 when the iPhone was introduced.

— Dr. Michael Mandel, TechNet study, February 7, 2012

See our earlier rough estimate of Apple’s employment effects: “Jobs: Steve vs. the Stimulus.”

— Bret Swanson

R.H. Stands for Regulatory Hubris

“It is the single worst telecom bill that I have ever seen.”

— Reed Hundt, Jan. 31, 2012

Isn’t this rich?

One of the most zealous regulators America has known says Congress is overstepping its bounds because it wants to unleash lots of new wireless spectrum but also wants to erect a few guardrails so that FCC regulators don’t run roughshod over the booming mobile broadband market.

At a New America Foundation event yesterday, former FCC chairman Reed Hundt said Congress shouldn’t micromanage the FCC’s ability to micromanage the wireless industry. Mr. Congressman, you don’t know anything about how the FCC should regulate the Internet. But the FCC does know how to build networks, run mobile Internet businesses, and perfectly structure a wildly tumultuous economic sector. It’s just the latest remarkable example of the growing hubris of the regulatory state.

In his book, You Say You Want a Revolution, Hundt famously recounted his staff’s interpretation and implementation of the 1996 Telecom Act.

The passage of the new law placed me on a far more public stage. But I felt Congress — in the constitutional sense — had asked me to exercise the full power of all ideas I could summon. And I believed that I and my team had learned, through many failures, how to succeed. Later, I realized that we knew almost nothing of the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.

…

Meeting in several overlapping groups of about a dozen people each . . . we dedicated almost three weeks to studying the possible readings of each word in the 150-page statute. The conference committee compromises had produced a mountain of ambiguity that was generally tilted toward the local phone companies’ advantage. But under the principles of statutory interpretation, we had broad authority to exercise our discretion in writing the implementing regulations. Indeed, like the modern engineers trying to straighten the Leaning Tower of Pisa, we could aspire to provide the new entrants to the local telephone markets a fairer chance to compete than they might find in any explicit provision of the law. In addition, the law gave almost no guidance about how to treat the Internet, data networks, . . . and many other critical issues. (Three years later, Justice Antonin Scalia agreed, on behalf of the Supreme Court, that the law was profoundly ambiguous.)

…

The more my team studied the law, the more we realized our decisions could determine the winners and losers of the new economy. We did not want to confer advantage on particular companies; that seemed inequitable. But inevitably

wink, wink,

a decision that promoted entry into the local market would benefit a company that followed such a strategy.

There are so many angles here.

(1) Hundt says he and his team basically stretched the statute to mean whatever they wanted. The law may have been ambiguous — and it was, I’m not going to defend the ’96 Act — yet the Supreme Court still found in a series of early-2000s cases that Hundt’s FCC had wildly overstepped even these flimsy bounds. That’s how aggressive and unconstrained Hundt was.

(2) Hundt’s rules helped crash the tech and telecom sectors in 2000-2002. His rules were so complex and intrusive that, whatever your views about the CLEC wars, the PCS C block spectrum debacle, and other battles, it’s hard to deny that the paralysis caused by the rules hurt broadband and the nascent Net.

(3) Is it surprising that, given the FCC’s poor record of reaching way past its granted powers, some in Congress want to circumscribe FCC regulators by giving them less-than-omnipotent authority? Is the new view of elite regulators that Congress should pass laws, the full text of which might read: “§1. Congress grants to the Internet Agency the authority to regulate the Internet. Go forth and regulate.”

(4) On the other hand, it’s not clear why Hundt would care particularly what Congress says in any new spectrum statute. He didn’t care much for the words or intent of the ’96 Act, and he thinks regulators should “aspire” to grand self-appointed projects. Who knows, maybe all those Supreme Court smack downs in the early 2000s made an impression.

(5) Hundt says he and his team later realized, in effect, how naive they were about “the complexity and importance of the tasks in front of the FCC.” So he’s acknowledging after things didn’t go so well that his FCC underestimated the complexity and thus overestimated their own expertise . . . yet he says today’s FCC deserves comprehensive power to structure the mobile Internet as it sees fit?

(6) Hundt admitted his FCC relished its capacity to pick winners and losers. Not particular companies, mind you — that would be improper — merely the types of companies who win and lose. A distinction without very much of a difference.

(7) We don’t argue that Congress, instead of the FCC, should impose intrusive regulation through statute. We don’t advocate long and complex laws. That’s not the point. Laws should be clear and simple, but stating the boundaries of a regulator’s authority is not a controversial act. No one should be imposing intrusive regulation or overdetermining the structure of an industry. And that’s what Congress — perhaps in a rare case! — is protecting against here.

Jobs’ jobs versus “jobs”

On Tuesday afternoon, Apple said it earned $13 billion in the fourth quarter on $46 billion in revenue. Thirty-seven million iPhones and 15 million iPads sold in the quarter helped boost its market cap to $415 billion. A few hours later, Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, in his State of the Union response message, contrasted the technology juggernaut with Washington’s impotent jobs efforts: “The late Steve Jobs – what a fitting name he had – created more of them than all those stimulus dollars the President borrowed and blew.”

First thing Wednesday morning, however, Paul Krugman countered with a devastating argument – “Mitch Daniels Doesn’t Read the New York Times.” Prof. Krugman referred to the first of the Times‘ multipart series on Apple’s Chinese manufacturing operations.

From Sunday’s Times:

Not long ago, Apple boasted that its products were made in America. Today, few are. Almost all of the 70 million iPhones, 30 million iPads and 59 million other products Apple sold last year were manufactured overseas.

…

Apple employs 43,000 people in the United States and 20,000 overseas, a small fraction of the over 400,000 American workers at General Motors in the 1950s, or the hundreds of thousands at General Electric in the 1980s. Many more people work for Apple’s contractors: an additional 700,000 people engineer, build and assemble iPads, iPhones and Apple’s other products. But almost none of them work in the United States. Instead, they work for foreign companies in Asia, Europe and elsewhere, at factories that almost all electronics designers rely upon to build their wares.

Steve Jobs designed great products. It’s very, very hard to make the case that he created large numbers of jobs in this country. Obama’s auto bailout, just by itself, saved a lot more jobs than Apple’s US employment.

So the New York Times thinks all those Chinese Foxconn assembly workers are the primary employment effect of Apple. And Prof. Krugman sidesteps the argument by noting the “auto bailout” – not the stimulus – “saved” – not created, mind you – more jobs than Apple’s under-roof American workforce.

CNNMoney jumped in:

Daniels’ math just doesn’t add up, no matter how successful and valuable Apple has become.

Not even close.

This little episode exposes quite a lot about the fundamentally different ways people think about the economy.

The economy is dynamic and complex. It’s a cooperative, competitive, and evolutionary. In recent pre-Great Recession history, the U.S. lost around 15 millions jobs every year — holy depression! But we created some 17 million a year, netting two million. There’s no way to quantify Jobs’ jobs impact exactly, which is one of the great virtues of capitalism.

An attempt to estimate in a very rough way, however, might be useful:

Apple

Apple has 60,000 total employees, around 43,000 in U.S.

Multiply these numbers by the years these jobs have existed, decades in the case of many. That’s many hundreds of thousands of “job-years.”

Then consider the broad software industry, especially the world of “apps” being developed for iPhone and iPad, and now for Macs. More than 500,000 iOS apps now exist, and 1.2 billion were downloaded in the last week of December 2011. Lots of people are trying to quantify how many jobs this app ecosystem has created. Likely it will mean many tens of thousands of jobs for decades to come, meaning hundreds of thousands of job-years, though even the “app” won’t look this way forever or even for long. We’ll see.

Apple computers, iPhones, iPads, and multimedia software, like OSX, iOS, Quicktime, and WebKit, drive the Internet and wireless industries. (WebKit is an open software platform developed by Apple that most people have never heard of. But it’s crucial to Internet browsers and webpage development.) These devices allow people and companies to create content. They improve productivity and create new kinds of jobs. How many graphic designers would we have had over the years without the Mac?

Apple devices devour bandwidth and storage and drive new generations of broadband and mobile network build-outs, totaling about $65 billion per year in the U.S. So add some significant portion of networking equipment salesmen and telecom pole-climbers and Verizon and Comcast workers and data center technicians. The iPhone alone completely reinvigorated the U.S. mobile industry and ushered in a new paradigm of computing, moving from PC to mobile device. Apple jolted AT&T back to life when the two companies partnered on the first iPhone. How many jobs across the economy did the iPhone “save” by boosting our digital industries when the PC era had about run its course? A lot.

Jobs created a new digital music industry. It’s impossible to gauge how many jobs were created versus eliminated. But clearly the new jobs are higher value jobs.

Apple is now the largest buyer of microchips in the world. It buys 23% of all the world’s flash memory, for example. Much of that is South Korean. But Apple probably buys something like 20 million Intel microprocessors each year. That’s a huge part of Intel’s business. Intel employs 100,000 people (not all in the U.S.).

The notion that “almost none” of the “additional 700,000” people who contribute to designing and building Apple products work in the U.S. is false. And silly.

Apple’s list of suppliers includes many of America’s leading-edge technology companies: Qualcomm, Intel, Corning, LSI, Broadcom, Seagate, Micron, Analog Devices, Linear, Maxim, Marvell, International Rectifier, Western Digital, ON Semi, Nvidia, AMD, Cypress, Texas Instruments, TriQuint, SanDisk, etc.

Lots of Apple’s foreign suppliers have substantial workforces in the U.S. Oft cited are the two Austin, Texas, Samsung fabs, which employ 3,500 workers who make NAND flash memory and Apple’s A5 chip. But many Asian and European Apple suppliers have sales, marketing, and support staff in America.

And of course no government or stimulus jobs are possible without private wealth creation. During the “stimulus” period — 2009-11 — Apple paid $16.5 billion in corporate income taxes, thus financing about 2% of the entire $821 billion stimulus package and thus 2% of the stimulus “jobs.” One might counter that stimulus was funded with debt, but money is fungible, and issuing debt depends on future claims on wealth. Moreover, because stimulus jobs were so extraordinarily expensive, a different accounting says that Apple’s $16.5 billion in taxes could have paid for 330,000 $50,000-a-year salaries.

Pixar

In 1986, Steve Jobs bought a tiny division of George Lucas’s LucasFilm and created what we know as Pixar, the leading movie animation studio. In 2006, Pixar merged with Walt Disney. Disney has 156,000 employees and $41 billion in sales, a growing portion of which directly or indirectly relate to Pixar properties, film development, characters, licensing, and distribution. Pixar really saved Hollywood during a dark time for film and spawned a whole new animation boom. Pixar developed and inspired many new technologies for film making, video games, and other interactive visual media.

An additional consideration: Over the 2009-11 period, Disney paid $7 billion in income taxes, thus financing just under 1% of the stimulus and 1% of the “jobs.” That $7 billion could have funded 140,000 $50,000-a-year salaries.

Macro

The economy-wide effects of Steve Jobs are of course impossible to measure with precision. But a new study from Robert Shapiro and Kevin Hassett estimates that advances in mobile Internet technologies boosted U.S. employment by around 400,000 per year from 2007 to 2011, or by a total of around 1.2 million over the 2009-11 stimulus period. The Phoenix Center found similar employment effects. What proportion of these can be attributed to Steve Jobs is, again, impossible to say. But it’s clear Apple was the primary innovator in mobile Internet technologies in this period, towering over a multitude of other important technologies. More than any other device, the iPhone exploited the new, larger-capacity 3G mobile networks of the period, and once it proved wildly popular it was the chief impetus for additional 3G mobile capacity.

Stimulus

CBO estimates ARRA (the Stimulus bill) yielded between 1.3 and 3.5 million job-years net, meaning created or saved. But as the stimulus wanes, many of these jobs go away, or at least are not attributable to the stimulus.

Robert Barro of Harvard questions whether ARRA created any jobs at all. He says the question isn’t whether the Keynesian multiplier is greater than 1 (meaning break even; spend $1, get $1 in GDP), let alone whether it’s 1.5 (spend a dollar, get $1.50), but whether the multiplier is greater than zero.

Stanford’s John Taylor also thinks ARRA had no positive effect.

And do stimulus-boosters really want to equate these two activities?

(1) the federal government pays a state worker’s salary for a year instead of the state paying the salary;

(2) a new job derived from an entrepreneur who’s created whole new industries with new kinds of higher value jobs that last for decades, spurring yet more growth and jobs.

In Keynesian macro world those two jobs are equivalent, I guess.

The CNNMoney report acknowledged the 43,000 U.S. employees of Apple and also the 850 employees of Pixar at the time it merged with Disney in 2006. It even allowed that perhaps Pixar could employ twice as many people now. It also grudgingly admitted that maybe some Americans are building apps for the App Store. That’s about it.

This imprecise exercise misses the deeper truths of entrepreneurial capitalism and short-changes the dynamic versus static view of the economy. In a new article today, which I just see as I’m finishing this post, Prof. Krugman quite rightly notes the importance of industrial clusters to growth. He cites the Chinese supply-chains highlighted in the NYT series. But he entirely ignores the most famous and successful cluster on earth — Silicon Valley. How many jobs in Silicon Valley do we think are dependent on or symbiotic with Apple. It’s incalculable, but its a lot.

I asked Gov. Daniels what he thought.

“I won’t be reading Herr Krugman,” Gov. Daniels replied, “but I did read the New York Times, and it changes nothing. Just means Dr. K doesn’t understand the dynamism of innovation, either.”

— Bret Swanson