That’s the question Jim Tankersley asked in a page one Washington Post story this week.

Here is how he summarized the situation:

“In the past three recoveries from recession, U.S. growth has not produced anywhere close to the job and income gains that previous generations of workers enjoyed. The wealthy have continued to do well. But a percentage point of increased growth today simply delivers fewer jobs across the economy and less money in the pockets of middle-class families than an identical point of growth produced in the 40 years after World War II.

That has been painfully apparent in the current recovery. Even as the Obama administration touts the return of economic growth, millions of Americans are not seeing an accompanying revival of better, higher-paying jobs.

The consequences of this breakdown are only now dawning on many economists and have not gained widespread attention among policymakers in Washington. Many lawmakers have yet to even acknowledge the problem. But repairing this link is arguably the most critical policy challenge for anyone who wants to lift the middle class.”

Tankersley cites the historical heuristic that a percentage point of GDP growth usually delivers about a half-point (0.5-0.6%) of employment growth.

“Three and a half years into the recovery that began in 2001 under President George W. Bush, job intensity was stuck at less than 0.2 percent. The recovery under President Obama is now up to an intensity of 0.3 percent, or about half the historical average.”

If we measure incomes, rather than employment, the situation appears even more dire:

“Middle-class income growth looks even worse for those recoveries. From 1992 to 1994, and again from 2002 to 2004, real median household incomes fell — even though the economy grew more than 6 percent, after adjustments for inflation, in both cases. From 2009 to 2011 the economy grew more than 4 percent, but real median incomes grew by 0.5 percent.”

What’s going on? Is the American middle class really in such bad shape? If so, why? And can we do anything about it? If not, why do these data appear to show a fundamental shift in the link between GDP growth and overall prosperity? These are big, complicated questions. For which I don’t have lots of concrete answers. I would, however, suggest a number of factors that may help us think about.

First, our economy does look different from the 1950s or 1960s. It is more complex. Back then, during a recession, factories laid off shifts of workers, leading to sharp employment downturns. Coming out of recessions, factories often hired back those same workers to build the same products. It was a simple process.

Today, although American manufacturing output is larger than ever, it employs a much smaller portion of the economy. The service and knowledge economies now dominate employment. And when jobs are not so closely tied to making widgets and the output is more ambiguous, the simple lay-off/hire-back formula disappears. In other words, we have lots more organizational and human capital today, and less “labor.”

This could be one reason the 1990 and 2001 recessions were shallower, but the job bounce-backs were slower.

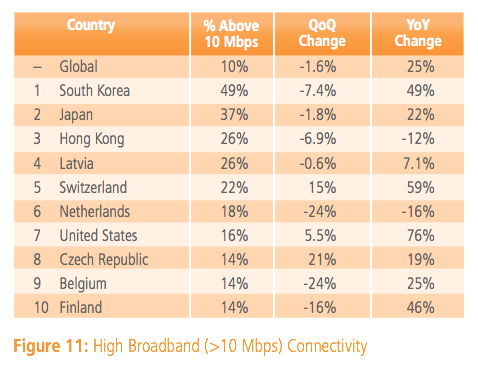

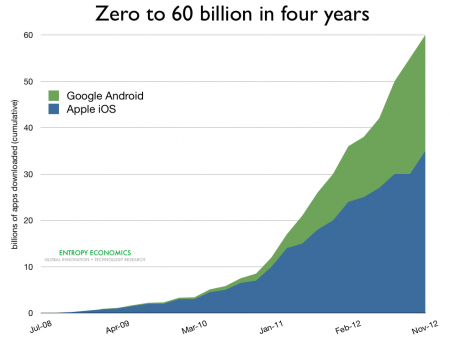

Another factor, which everyone points out, is education. The United States may dominate many of the high-end professions in technology and finance because we have large cohorts of highly educated people (and immigrants). During the Great Recession and its aftermath, for example, the new App Economy, based on smartphones, broadband, and software, has created an estimated 500,000-600,000 jobs. Perhaps an also large cohort, however, not nearly as well educated or without the necessary knowledge skills, has been caught in a two-decade wave of globalization that quickly reduced the jobs this cohort was used to doing, without the possibility for quick changes to higher-value industries.

The Great Recession, however, was deeper and its employment rebound slower than the 1990 and 2001 recessions.

So we look to other factors that appear to be suppressing employment. In his new book The Redistribution Recession, University of Chicago economist Casey Mulligan argues that a host of well-intended safety-net programs are the chief culprit. Unemployment insurance, disability payments, the minimum wage, Medicaid, the earned income tax credit, food stamps and other programs can create deep disincentives to work and/or hire. Mulligan estimated that the average marginal tax rate on the relevant population increased eight percentage points, from 40% to 48%, during the Great Recession. For many individuals and families, the complex effects of these programs conspire to yield 100% marginal tax rates — that is, an extra dollar earned loses a dollar or more in benefits and taxes.

I would throw out another possible factor: monetary policy. The Fed’s unorthodox zero-interest-rate-plus-bond-buying policy has created free money for large firms and for government. We see government growing and corporate profits at record highs. But for small and medium-sized firms, credit is being rationed by regulators. Low rates are meaningless if credit is unavailable. The slow recovery for small firms, which are often acknowledged to create most jobs, could be part of the equation.

Switching from employment to income, a few factors are commonly mentioned:

- Education and globalization may, as with employment, be boosting income for the top but limiting income prospects for the broad middle.

- Health care and other benefits are rising as a portion of overall compensation, thus limiting the measured portion that we call wages or salaries.

- Immigration has added millions of low-wage workers that may depress average measured incomes. These particular workers may be much better off than they were in their home countries and, by lowering wages for jobs few Americans want to do, may “harm” only a very small number of Americans.

- Many income measures do not account for taxes and larger transfer payments in recent times through EITC, Medicaid, disability, unemployment, food stamps, etc. When these are factored in, the numbers look much different.

Alan Reynolds made the case for these underestimates in his 2006 book, Income and Wealth. And now Bruce D. Meyer of the University of Chicago and James X. Sullivan of Notre Dame find that median income growth has not suffered nearly as much as the conventional wisdom says.

“After appropriately accounting for inflation, taxes, and noncash benefits, we show that median income rose by more than 50 percent over the past three decades. This increase is considerably greater than the gains implied by official statistics—official median income rose by only 14 percent between 1980 and 2009. Our improved measure of income increased in each of the past three decades, although the growth has been much slower since 2000. Median consumption also rose at a similar rate over the whole period but at a faster rate than income over the past decade.”

The real income slowdown in the 2000s is not surprising. The decade included two recessions—including the big one. The decade also saw, for the first time since the 1970s, a good whiff of inflation, especially in food, fuel, and housing. Add in spiraling health care and education costs. So, despite spectacular gains in computers, communications, and consumer goods, the middle class squeeze often seems real.

Mark Perry and Don Boudreaux, however, are even more emphatic than Meyer and Sullivan. They say the “trope” of the stagnant middle class is “spectacularly wrong”:

“It is true enough that, when adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index, the average hourly wage of nonsupervisory workers in America has remained about the same. But not just for three decades. The average hourly wage in real dollars has remained largely unchanged from at least 1964—when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) started reporting it.

“Moreover, there are several problems with this measurement of wages. First, the CPI overestimates inflation by underestimating the value of improvements in product quality and variety. Would you prefer 1980 medical care at 1980 prices, or 2013 care at 2013 prices? Most of us wouldn’t hesitate to choose the latter.

“Second, this wage figure ignores the rise over the past few decades in the portion of worker pay taken as (nontaxable) fringe benefits. This is no small matter—health benefits, pensions, paid leave and the rest now amount to an average of almost 31% of total compensation for all civilian workers according to the BLS.

“Third and most important, the average hourly wage is held down by the great increase of women and immigrants into the workforce over the past three decades. Precisely because the U.S. economy was flexible and strong, it created millions of jobs for the influx of many often lesser-skilled workers who sought employment during these years.”

Perry and Boudreaux go on to say that no income figures—whether the officially stagnant ones or the higher adjusted figures—can account for the dramatic rise in the quantity and quality of consumption that income yields.

“Bill Gates in his private jet flies with more personal space than does Joe Six-Pack when making a similar trip on a commercial jetliner. But unlike his 1970s counterpart, Joe routinely travels the same great distances in roughly the same time as do the world’s wealthiest tycoons.

What’s true for long-distance travel is also true for food, cars, entertainment, electronics, communications and many other aspects of ‘consumability.’ Today, the quantities and qualities of what ordinary Americans consume are closer to that of rich Americans than they were in decades past. Consider the electronic products that every middle-class teenager can now afford—iPhones, iPads, iPods and laptop computers. They aren’t much inferior to the electronic gadgets now used by the top 1% of American income earners, and often they are exactly the same.”

Despite all the factors in this multifaceted debate, one thing is certain. Economic growth is better for the middle class than is economic stagnation.