Amazing! An iPhone is more capable than 13 distinct electronics gadgets, worth more than $3,000, from a 1991 Radio Shack ad. Buffalo writer Steve Cichon first dug up the old ad and made the point about the seemingly miraculous pace of digital advance, noting that an iPhone incorporates the features of the computer, CD player, phone, “phone answerer,” and video camera, among other items in the ad, all at a lower price. The Washington Post‘s tech blog The Switch picked up the analysis, and lots of people then ran with it on Twitter. Yet the comparison was, unintentionally, a huge dis to the digital economy. It massively underestimates the true pace of technological advance and, despite its humor and good intentions, actually exposes a shortcoming that plagues much economic and policy analysis.

Amazing! An iPhone is more capable than 13 distinct electronics gadgets, worth more than $3,000, from a 1991 Radio Shack ad. Buffalo writer Steve Cichon first dug up the old ad and made the point about the seemingly miraculous pace of digital advance, noting that an iPhone incorporates the features of the computer, CD player, phone, “phone answerer,” and video camera, among other items in the ad, all at a lower price. The Washington Post‘s tech blog The Switch picked up the analysis, and lots of people then ran with it on Twitter. Yet the comparison was, unintentionally, a huge dis to the digital economy. It massively underestimates the true pace of technological advance and, despite its humor and good intentions, actually exposes a shortcoming that plagues much economic and policy analysis.

To see why, let’s do a very rough, back-of-the-envelope estimate of what an iPhone would have cost in 1991.

In 1991, a gigabyte of hard disk storage cost around $10,000, perhaps a touch less. (Today, it costs around four cents ($0.04).) Back in 1991, a gigabyte of flash memory, which is what the iPhone uses, would have cost something like $45,000, or more. (Today, it’s around 55 cents ($0.55).)

The mid-level iPhone 5S has 32 GB of flash memory. Thirty-two GB, multiplied by $45,000, equals $1.44 million.

The iPhone 5S uses Apple’s latest A7 processor, a powerful CPU, with an integrated GPU (graphics processing unit), that totals around 1 billion transistors, and runs at a clock speed of 1.3 GHz, producing something like 20,500 MIPS (millions of instructions per second). In 1991, one of Intel’s top microprocessors, the 80486SX, oft used in Dell desktop computers, had 1.185 million transistors and ran at 20 MHz, yielding around 16.5 MIPS. (The Tandy computer in the Radio Shack ad used a processor not nearly as powerful.) A PC using the 80486SX processor at the time might have cost $3,000. The Apple A7, by the very rough measure of MIPS, which probably underestimates the true improvement, outpaces that leading edge desktop PC processor by a factor of 1,242. In 1991, the price per MIPS was something like $30.

So 20,500 MIPS in 1991 would have cost around $620,000.

But there’s more. The 5S also contains the high-resolution display, the touchscreen, Apple’s own M7 motion processing chip, Qualcomm’s LTE broadband modem and its multimode, multiband broadband transceiver, a Broadcom Wi-Fi processor, the Sony 8 megapixel iSight (video) camera, the fingerprint sensor, power amplifiers, and a host of other chips and motion-sensing MEMS devices, like the gyroscope and accelerometer.

In 1991, a mobile phone used the AMPS analog wireless network to deliver kilobit voice connections. A 1.44 megabit T1 line from the telephone company cost around $1,000 per month. Today’s LTE mobile network is delivering speeds in the 15 Mbps range. Wi-Fi delivers speeds up to 100 Mbps (limited, of course, by its wired connection). Safe to say, the iPhone’s communication capacity is at least 10,000 times that of a 1991 mobile phone. Almost the entire cost of a phone back then was dedicated to merely communicating. Say the 1991 cost of mobile communication (only at the device/component level, not considering the network infrastructure or monthly service) was something like $100 per kilobit per second.

Fifteen thousand Kbps (15 Mbps), multiplied by $100, is $1.5 million.

Considering only memory, processing, and broadband communications power, duplicating the iPhone back in 1991 would have (very roughly) cost: $1.44 million + $620,000 + $1.5 million = $3.56 million.

This doesn’t even account for the MEMS motion detectors, the camera, the iOS operating system, the brilliant display, or the endless worlds of the Internet and apps to which the iPhone connects us.

This account also ignores the crucial fact that no matter how much money one spent, it would have been impossible in 1991 to pack that much technological power into a form factor the size of the iPhone, or even a refrigerator.*

Tim Lee at The Switch noted the imprecision of the original analysis and correctly asked how typical analyses of inflation can hope to account for such radical price drops. (Harvard economist Larry Summers recently picked up on this point as well.)

But the fact that so many were so impressed by an assertion that an iPhone possesses the capabilities of $3,000 worth of 1991 electronics products — when the actual figure exceeds $3 million — reveals how fundamentally difficult it is to think in exponential terms.

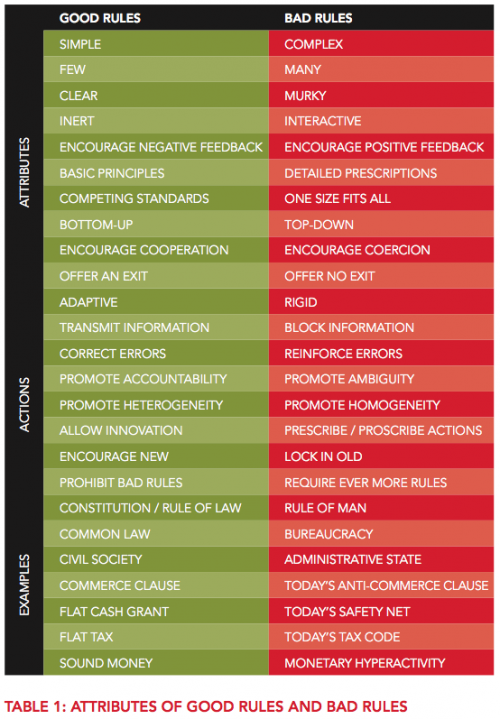

Innovation blindness, I’ve long argued, is a key obstacle to sound economic and policy thinking. And this is a perfect example. When we make policy based on today’s technology, we don’t just operate mildly sub-optimally. No, we often close off entire pathways to amazing innovation.

Consider the way education policy has mostly enshrined a 150-year-old model, and in recent decades has thrown more money at the same broken system while blocking experimentation. The other day, the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen (@pmarca) noted in a Twitter missive the huge, but largely unforeseen, impact digital technologies are having on this industry that so desperately needs improvement:

“Four biggest K-12 education breakthroughs in last 20 years: (1) Google, (2) Wikipedia, (3) Khan Academy, (4) Wolfram Alpha.”

Maybe the biggest breakthroughs of the last 50 years. Point made, nonetheless. California is now closing down “coding bootcamps” — courses that teach people how to build apps and other software — because many of them are not state certified. This is crazy.

The importance of understanding the power of innovation applies to health care, energy, education, and fiscal policy, but no where is it more applicable than in Internet and technology policy, which is, at the moment, the subject of a much needed rethink by the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

— Bret Swanson

* To be fair, we do not account for the fact that back in 1991, had engineers tried to design and build chips and components with faster speeds and greater capacities than the consumer items mentioned, they could have in some cases scaled the technology in a more efficient manner than, for example, simply adding up consumer microprocessors totaling 20,500 MIPS. On the other hand, the extreme volumes of the consumer products in these memory, processing, and broadband communications categories, are what make the price drops possible. So this acknowledgment doesn’t change the analysis too much, if at all.