- The info-tech solution to re-open the economy – Indianapolis Business Journal – April 10, 2020

- The Internet vs. COVID-19 – AEIdeas – April 9, 2020

- Information is the key to defeating COVID-19 – AEIdeas – March 25, 2020

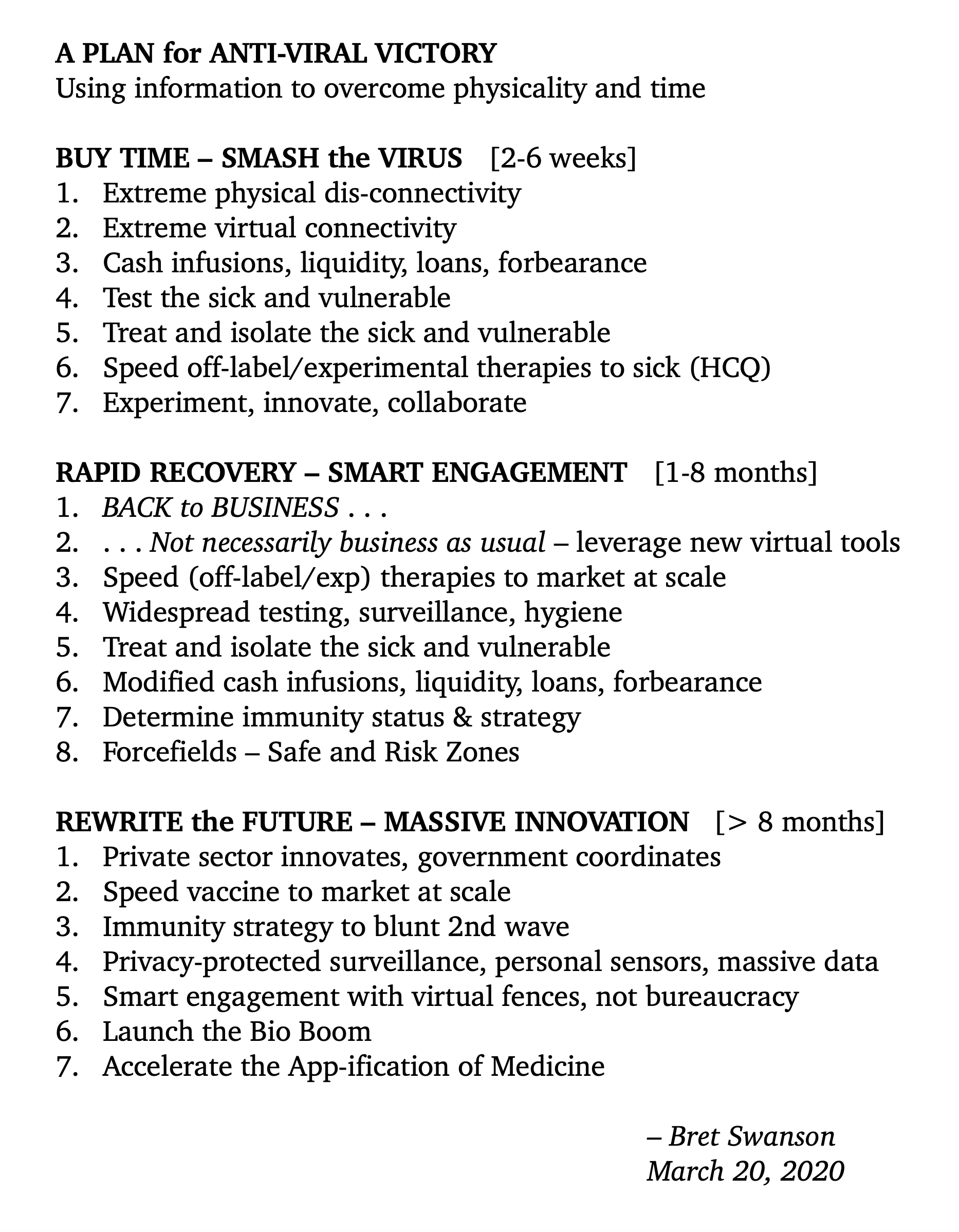

- A Plan for Anti-Viral Victory – Maximum Entropy – March 20, 2020

My recent COVID-19 commentary . . .

Information is the key to defeating COVID-19

The chief constraints on the world are physical and temporal. Abundant information, however, helps us evade and sometimes conquer these facts of life. Without the internet, life in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic would be far nastier and more brutish, even more solitary, and shorter, too.

In our current predicament, the fundamental shortcomings of space and time are amplified. SARS-CoV-2 can’t replicate without our cells and our proximity to each other. So we separate for a period longer than the viral lifetime. Yet our bodies need calories, and time does not stop for debts and rents to be paid.

So we must buy time with information.

Extreme physical dis-connectivity requires extreme virtual connectivity. The speed of the virtual scale-up has been impressive. Teachers have adroitly shifted to meet with 30 million school children online. Colleges the same. Zoom video conferencing has spread faster than the virus, and Microsoft Teams added 12 million users in just one week, growing by more than a third to 44 million. Communities are leveraging social networks to support neighbors in a crunch. The government is (finally!) allowing doctors and patients to use FaceTime and Skype for remote video check-ups. The American internet infrastructure has handled increased demand admirably, with internet service providers and mobile carriers adding capacity and suspending data usage limits.

Not every activity can be replicated online, however. And so we call on the wealth generated by our information-rich economy. Cash infusions, liquidity, loans, and forbearance can smooth away the sudden halt of face-to-face work — at least for a time. Massive investments in hospitals and medical supplies will save many of today’s ill, and tomorrow’s too. Wealth in a very real sense is resilience.

But wealth must be constantly regenerated. We can only rely on past productivity for so long. And so we must get back to work — as quickly as possible, in as many places as possible.

From macro to micro

We must replace our crucial macro response with an equally crucial micro recovery. Our initial macro efforts were broad, blunt, and indiscriminate. And understandably so. We didn’t have enough information to finely tune closings and distancing for particular people and places, nor to support earlier, more comprehensive travel bans, which would have been even more controversial. God willing, our macro efforts will spare large parts of the nation from intense breakouts of the type ravaging Milan, New York, and Seattle.

We need to think about the next phase, however. To fully support our heroic medical community in hard-hit places and vulnerable Americans everywhere, we must quickly reignite as much of the economy as possible. And we can only do so with better information.

Our micro efforts to target people, places, and things, and to collect exabytes of data, will be central. Which people and places are safe to return to work and school? For that, we need widespread testing. Which travel routes are safe? Which hospitals need (or can spare) extra capacity and supplies? Which early off-label and experimental therapies are showing the most promise? What are the immunity characteristics of COVID-19? Who contracted it without knowing it? And how will these answers inform our immunity strategy for any second wave this fall?

Better information can support a strategy of smart engagement. Without it, blunt macro policies will prevent the agility necessary in the days ahead. These efforts will require a heroic scale-up of information gathering tools and ideas. Most of them will not come from government (which will need to play a supporting and coordinating role), but from private firms and organizations.

The app-ification of medicine

We can launch a new era in radically decentralized personal medicine — for better individual health, an explosion in physician productivity, a research renaissance into new therapies, and far better public health surveillance.

In the future, massive data will detect outbreaks and smash them early, and most of the world economy can go on while risk zones are isolated and treated. Surveillance does not mean government watching your sneezes or temperature. It means mostly anonymous data collection, perhaps by third parties who can detect outbreaks and issue alerts. The goal is not zero cases. Such a goal would turn the government into an authoritarian police state. To protect both public health and private liberties, this is going to have to be a true public-private partnership.

All these things will require the FDA, CDC, and other federal agencies to adopt a new ethos of innovation, or to get out of the way. It will not come naturally. But these events must shake us out of our dangerous complacencies: the CDC’s faulty and thus delayed test; the FDA’s initial resistance to off-label and experimental therapies; the FDA’s reported resistance to Apple incorporating more health sensors and apps into the iPhone and Apple Watch.

A new bio boom The ultimate information tool is our understanding of the genome and all the “omics.” Although young, computational biology and related fields are now advancing at an astounding pace. They helped decode SARS-CoV-2’s genetic sequence in record time and, God willing, will help deliver a vaccine in record time as well. These codes of life can, along with our information technologies, lead to healthier bodies and more invaluable time with each other.

This article originally appeared at AEIdeas.

A Plan for Anti-Viral Victory

Sensing despair in the moment, I outlined a path to recovery. Originally on Twitter . . . .

A PLAN for ANTI-VIRAL VICTORY — Leveraging information to overcome our physical and temporal challenges

Health & economy are intertwined. After much-needed adoption of major behavioral modifications, we now should prepare for pivot to Rapid Recovery. pic.twitter.com/46vlQIVWhZ — Bret Swanson (@JBSay) March 20, 2020

Prolonged economic paralysis will undermine crucial health efforts. We can creatively leverage our extraordinary broadband information infrastructure for much of the economy. But we should restart the physical economy in as many places as possible, as soon as possible.

Encouraging news that pharma firms are providing big supplies – tens of millions of pills – of off-label drugs (eg HCQ) that *appear* to be effective vs. Covid-19. More speed on more fronts will help immediately – AND set new innovation-tilting precedents.

We can also launch a new era in personal medicine, with massive data so that future outbreaks can be detected and smashed early, and so most of the world economy can go on while Risk Zones are isolated and treated.

Surveillance does not mean government watching your sneezes or temperature. It means anon data collection, perhaps by third parties who can detect outbreaks and issue alerts. The goal is not ZERO cases. Such a goal would turn the government into an authoritarian police state.

Our problems are chiefly physical and temporal. We can use information to mitigate some physical and temporal dislocations, and for those we can’t, we will call on the wealth of our info-rich economy to smooth away the viral lifetime.

A short-term silver lining can be a new focus on teamwork, shared humanity, and practicality over pettiness.

A medium-term silver lining could be speedier adoption by the physical economy of information tools that can make them more productive and creative.

A long-term silver lining can be a new commitment to radical bio innovation and a transformed (better/less expensive) health sector, an acceleration of the App-ification of Medicine.

McKitrick’s wisdom on the state of the climate debate

Must reading from the excellent environmental economist Ross McKitrick:

“The old compromise is dead. Stop using C jargon in your speeches. Start learning the deep details of the science and economics instead of letting the C crowd dictate what you’re allowed to think or say. Figure out a new way of talking about the climate issue based on what you actually believe. Learn to make the case for Canada’s economy to survive and grow.

“You, and by extension everyone who depends on your leadership, face an existential threat. It was 20 years in the making, so dig in for a 20-year battle to turn it around. Stop demonizing potential allies in the A camp; you need all the help you can get.

“Climate and energy policy has fallen into the hands of a worldwide movement that openly declares its extremism. The would-be moderates on this issue have pretended for 20 years they could keep the status quo without having to fight for it. Those days are over.”

Seizing the 5G mid-band spectrum opportunity

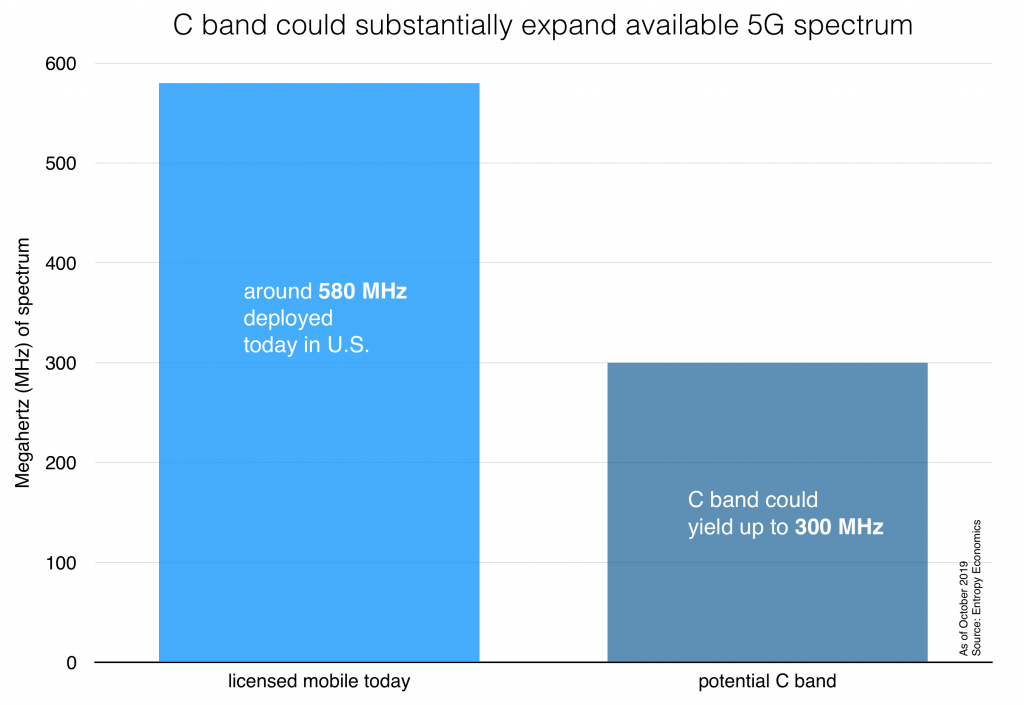

Tomorrow, the House Energy and Commerce Committee will hear testimony on one of the spectrum bands most important to the future of 5G wireless. Known as the C-Band, the frequencies are located between 3.7 and 4.2 gigahertz (GHz), which is a kind of sweet spot in the fundamental tradeoff between distance and data rates for all wireless technologies. The spectrum is perfect for the new 5G architecture, which will rely on hundreds of thousands or even millions of small cells, already popping up across the country and around the world.

Right now, however, this band is used by three satellite firms (Intelsat, SES, and Telesat) to broadcast video and radio content to cable TV and radio ground stations for further delivery via terrestrial networks to consumers. Technology is changing this market, however. Increasingly, video and radio content is delivered to distribution points via fiber optic lines, not satellite, and so the satellite firms are left with extra spectrum, and they’d like to sell it. Which works out perfectly. Because the mobile firms would love to buy it for 5G.

The spectrum is not only perfectly situated for small cell deployments, but there’s also a lot of it. Out of the 500 MHz total held by the satellite firms today, potentially 300 MHz could be auctioned to the mobile firms. To get an idea of how much 300 MHz is, consider that today in the U.S. the mobile firms operate their networks with a deployed spectrum total of only around 580 MHz. So the C band could more than double today’s mobile airwaves.

That’s great news. But moving this spectrum from one set of users and technologies to another can be tricky. A group called the C Band Alliance has proposed a novel mechanism where the satellite firms would, under the supervision of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), auction a big portion of the 500 MHz directly to the bidding mobile firms. They think the process of auctioning, repacking, and deploying the spectrum, along with necessary ground station and fiber optic upgrades, could be accomplished in two to three years.

Other firms, however, favor a series of incentive auctions run by the FCC. This second group claims the auctions could be done quickly. But that would belie all experience, where auctions this complex would likely take at least several more years, or more than double the time, of the C Band Alliance proposal.

It’s impossible to predict exactly how each proposal would work, and how long it would take. But given the importance of 5G to U.S. economy, at this point I favor speed, which means moving ahead with the C Band Alliance proposal.

For more on 5G, mid-band spectrum, and the economic implications, see some of our other recent items:

Filling the mid-band spectrum gap to sustain 5G momentum

If your content doesn’t appear on Google or Twitter, do you exist?

In the world of attention-getting, getting banished or downgraded on the world’s key attention platforms is frustrating. Or worse. The latest example is a claim of invisibility by Democratic presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard. She claims that after the June presidential debate, just as she was gaining steam from a solid performance, Google deactivated the ads she had purchased on its platform, blocking people from finding her content when they searched for her.

In recent days, most of the claims of blocking, throttling, shadow-banning, and demonetization on digital platforms has come from conservatives. Gabbard is a progressive, but some wonder whether her status as an outsider – as many of the conservatives are – is even more central to the seeming trend of suppression. Gabbard is suing Google for $50 million. She says Google’s excuses for why it deactivate her account for several crucial hours, before reactivating it, don’t add up. Much of her legal brief is couched in the Constitution.

To this non-lawyer, Gabbard’s complaint seems rather weak. At least legally. The First Amendment protects Americans from government encroachments on speech, religion, and assembly. The Constitution doesn’t guarantee citizens the positive right to be heard on private platforms. What’s more, the big tech firms enjoy their own First Amendment rights.

And yet, just because Gabbard’s complaint is feeble with regard to the First Amendment doesn’t mean it lacks substance as an example of a very real problem on the Internet. The blocking and throttling of Internet data based on viewpoints may not violate the Constitution, but it does violate our sense of fairness and our idea of what the Internet should be – a generally free and open platform for communication and content.

(more…)Apollo, mankind, and Moore’s law

When Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins went to the moon 50 years ago this week, they had a large portion of the world’s computing power with them on Columbia and Eagle and behind them in Houston. One NASA engineer estimated that, between 1962 and 1967, the Apollo program had purchased 60 percent of all integrated circuits built in the US.

An image of the Saturn V rocket, which launched the Apollo 11 astronauts into space, is projected onto the side of the Washington Monument to mark the 50th anniversary of the first lunar mission in Washington, DC July 16, 2019 – via REUTERS

Today, however, that overwhelming proportion seems paltry in its aggregate power. The two Apollo Guidance Computers (AGC) onboard the spacecraft, for example, each contained 32 kilobits of random-access memory and 72 kilobytes of read-only memory. The AGCs had a primary clock running at 2.048 megahertz, and their 2,048 integrated circuits contained only several tens of thousands of transistors. They also weighed 70 pounds.

By comparison, today’s iPhone XS sports 32 gigabits of dynamic random-access memory, 256 gigabytes of storage, and a processor with 6.9 billion transistors running at 2.49 gigahertz. That’s a million times more memory, several million times more storage, and hundreds of millions times more processing power than the AGCs. All in a package one-hundredth the weight.

Even in the late 1960s, however, NASA had begun enjoying the early fruits of Moore’s law. As The Wall Street Journal noted in one of its many impressive articles on Apollo 11’s anniversary, “the first computer chips tested by MIT” — which built the AGCs — “cost $1,000 each. By the time astronauts landed on the moon, the price had dropped to $15 apiece. . . . It set a pattern of innovation, quality control and price-cutting that persists in the computer business to this day.”

In another article about the software team, which had to do so much with such limited hardware, The Wall Street Journal described the tense moments just before landing on the moon, when the mission was nearly aborted:

Neil Armstrong hovered a few miles above the surface of the moon on July 20, 1969, searching for a safe place to make history.

Only minutes of fuel remained to land the first men on another world. A power meter failed in Apollo 11’s cramped lunar lander. Communications faded in and out. Then, warnings began flashing: Program alarm. Program alarm.

Five times the onboard computer signaled an emergency like none Armstrong and crewmate Buzz Aldrin had practiced.

In that moment, the lives of two astronauts, the efforts of more than 300,000 technicians, the labor of eight years at a cost of $25 billion, and the pride of a nation depended on a few lines of pioneering computer code.

Read the entire article and the related content. And of course watch last year’s feature film “First Man” and this year’s documentary “Apollo 11.” Looking back, Apollo 11’s skimpy digital capacity only amplifies the engineers’ creativity and genius and the astronauts’ bravery. With today’s technical capabilities and a little of their vision and determination, who knows what giant leaps are possible?

This item was originally published at AEIdeas.

Deplatforming and disinformation will degrade our democracy

We spent much of the last two decades talking about ways to expand access to information — boosting broadband speeds, extending mobile coverage, building Wikipedia and Google and Github. But now that the exafloods have washed over us, with more waves on the way, many of our new challenges are the result of information overload.

In a world of digital overabundance, how do we protect our privacy and our children’s innocence? How do we highlight the important stuff and block the nonsense? How do we filter, sort, safeguard, and verify?

Information is the currency of a culture and the basis of learning and growth. The information explosion has enriched us innumerably. But if we don’t successfully grapple with some of the downsides, we will forfeit this amazing gift.

Two of today’s biggest threats are disinformation (the spreading of false or misleading content) and deplatforming (blocking access to or manipulating some information hub). Neither is entirely new. But in our networked world, both effects are supercharged, and they strike at the heart of our society’s ability to process information effectively.

The founders thought our democratic experiment required an educated and informed citizenry. The growth of our experiment, likewise, requires the ability to generate new knowledge, which, in turn, requires disagreement, debate, and creativity. Without a grasp of reality and good faith efforts to generate new knowledge, however, the system can founder.

Over the last two years, we heard much about foreign disinformation campaigns targeting the 2016 election. But we’ve now learned that many of these alarmist charges were themselves elaborate disinformation campaigns. Fraudulent documents were pumped into our law enforcement agencies and sprinkled across the government and media. The social media tools used in modest, mostly ineffective ways by Russian trolls were then repurposed in the 2017 and 2018 elections by American political groups posing as anti-disinformation scientists. The self-described investigators of disinformation have in fact become the purveyors of disinformation.

A rational response to spam, vice, disinformation, or mere poor quality is to filter, sort, and prioritize. Thus institutions of all kinds make legitimate decisions to carry or disallow content or activity on their platforms.

Apple, for example, keeps drugs, gambling, and sex, among other vices, off of its App Store. That’s a perfectly good strategy for Apple, its customers, and society. Platforms have the right to develop their own product and culture. Some form of gatekeeping or prioritization at some nodes of our shifting networks will always be necessary.

Our sense of fairness, however, is offended when a supposedly open platform makes arbitrary or outright discriminatory decisions. If, for example, a platform doesn’t want to host political or scientific discussions, fine. But when a platform pretends to host broad ranges of content, including political, social, and scientific debate, then we expect some measure of neutrality.

In the last few years, however, these hubs have increasingly been captured by political activists, their own internal ideologies, or go-with-the-flow fads. Social networks, content repositories, and now even payment networks are deplatforming content and people deemed socially unacceptable. Many of those kicked off the platforms are thoroughly despicable characters, for sure. But mainstream activists, academics, thinkers, and even rival platforms are increasingly getting blocked, shadow banned, or otherwise suppressed by, for example, Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Patreon, and PayPal. In fact, disinformation campaigns are a common way that rival activists get the hubs to deplatform enemies.

These tactics aren’t unique to the internet, of course. Disinformation is as old as time, or at least human warfare. And deplatforming is an unsavory trend on university campuses and academic journals, which are information hubs of a sort. Networks, however, amplify the power of these tactics. And so the new strategy of ideological badgering can also be found, and is especially potent, at large network nodes. Thus BlackRock, the $6-trillion family of index funds, which owns large percentages of all publicly traded companies, has become one of the activists’ juiciest targets. Instead of heckling every public firm or pension fund to do their political bidding, the activists successfully lobbied BlackRock to establish a “Stewardship Committee” to enforce their views, thus gaining some measure of control over all public firms without ownership of the firms.

The most astonishing current case is perhaps the most dangerous. It involves the apparent abuse of the government’s most powerful and sensitive surveillance tools and databases – the ultimate information platform — by political actors for political ends.

One structural solution to the politicization of centralized incumbents is to build rival institutions and decentralized platforms. arXiv is an alternative to traditional academic publishing, for example, and alternative news outlets continue to proliferate. Crypto- or blockchain-based peer-to-peer systems may be another way of disempowering the politicized platforms.

The current digital platforms might still regain some measure of public trust by recommitting to political and scientific neutrality (and to privacy, etc.). If they don’t, however, rival platforms will only grow faster. Washington, meanwhile, will be even more tempted to step in to regulate who can speak, what they can say, when, where, and how. In a misguided effort to bolster outcast speakers, free speech, a foundation of our system and our nation, will in fact likely suffer.

Some information platforms, such as law enforcement and intelligence, however, will inevitably remain unrivaled and centralized. And here we need a recommitment to professionalism, nonpartisanship, adult judgment, and farsighted citizenship.

Instead, our leadership class over the last many years has been a profound embarrassment. Perhaps poisoned by information overdose, government officials, public intellectuals, and journalists in their 50s, 60s, and 70s have behaved like the worst combination of toddlers and teenagers, gullible and paranoid, narrow-minded and spiteful. Supposedly educated and civilized men and women go on years-long rants on cable TV, while straight news has descended to its least accurate point ever. The commoditization of “the facts” has paradoxically expanded the field for factless nonsense.

What’s worse, closing off the spaces for rational inquiry will only deepen the social vertigo and prevent the course corrections needed to regain our individual and social balance. Despite all the real technological solutions to the challenge of information overload, human leadership and loftier social expectations may prove most important. To regain our balance, we desperately need our powers of science and civic discussion. Hold the current bad actors accountable, yes. But then we need to deescalate. Be skeptical — and invite skepticism of ourselves. Curate platforms for quality, but do not spitefully or ideologically discriminate. Be tough but generous and open.

The country needs robust information tools to defend itself and promote freedom across the globe. By information tools, I mean not just our military and intelligence capabilities. I refer also to free speech, science, and our open society. We cannot survive if these awesome powers are politicized and polluted.

This post originally appeared at AEIdeas – https://www.aei.org/publication/deplatforming-and-disinformation-will-degrade-our-democracy/

5G wireless, fact and fiction

New wireless technologies, including 5G, are poised to expand the reach and robustness of mobile connectivity and boost broadband choices for tens of millions of consumers across the country. We’ve been talking about the potential of 5G the last few years, and now we are starting to see the reality. In a number of cities, thousands of small cells are going up on lampposts, utility poles, and building tops. I’ve discussed our own progress here in Indiana.

The project will take many years, but it’s happening. And the Federal Communications Commission just gave this massive infrastructure effort a lift by streamlining the rules for deploying these small cells. Because of the number of small cells to be deployed – many hundreds of thousands across the country – it would be counterproductive to treat each one of them as a new large structure, such as a building or hundred-foot cell tower. The new rules thus encourage fast deployment by smoothing the permitting process and making sure cities and states don’t charge excessive fees. The point is faster deployment of powerful new wireless networks, which will not only supercharge your smartphone but also provide a competitive alternative to traditional wired broadband.

Given this background, I found last week’s editorial by the mayor of San Jose, California, quite odd. Writing in the New York Times, Mayor Sam Liccardo argued that the new FCC rules to encourage faster deployment are an industry effort to “usurp control over these coveted public assets and utilize publicly owned streetlight poles for their own profit, not the public benefit.”

But the new streamlining rules do no such thing. Public rights of way will still be public. Cities and states will still have the same access as private firms, just as they had before. And who will benefit by the private investment of some $275 billion dollars in new wireless networks? That’s right – the public.

If cities and states wish to erect new Wi-Fi networks, as Mayor Liccardo did in San Jose, they can still do so.

I think the real complaint from some mayors is that the new FCC rules will limit their ability to extort wildly excessive fees and other payments from firms who want to bring these new wireless technologies to consumers. Too often, cities are blocking access to these rights of way, unless firms pay up. These government games are the very obstacles to deployment that the FCC rule is meant to fix.

Fewer obstacles, faster deployment. And accelerated deployment of the new 5G networks will mean broader coverage, faster speeds, and more broadband competition, which, crucially, will put downward pressure on connectivity prices, boosting broadband availability and affordability.

Mayor Liccardo emphasizes the challenges of low-income neighborhoods. But there are much better ways to help targeted communities than by trying to micromanage – and thus delay – network deployment. One better way, for example, might be to issue broadband vouchers or to encourage local non-profits to help pay for access.

This isn’t an either-or problem. Cities still maintain access to public rights of way. But one thing’s for sure. Private firms will be the primary builders of next generation networks. Overwhelmingly so. And faster deployment of wireless networks is good for the public.

This year’s Nobel for economics is a technology prize!

On Tuesday, the Royal Swedish Academy awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in economic sciences to two American economists, William Nordhaus of Yale University and Paul Romer of New York University’s Stern School of Business. Romer is well-known for his work on innovation, and although the committee focused on Nordhaus’ research on climate change, this year’s prize is really all about technology and its central role in economic growth.

Paul Romer, who with William Nordhaus received the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, speaks at the New York University (NYU) Stern School of Business in New York City, October 8, 2018 – via REUTERS

Romer’s 1990 paper “Endogenous technological change” is one of the most famous and cited of the past several decades. Until then, the foundational theory of economic growth was Robert Solow’s model. It said growth was the result of varied quantities of capital and labor, which we could control, and a vague factor known as the Residual, which included scientific knowledge and technology. The Residual exposed a big limitation of the Solow model. Capital and labor were supposedly the heart of the model, and yet technology accounted for the vast bulk of growth — something like 85 percent, compared to the relatively small contributions of capital and labor. Furthermore, technology was an “exogenous” factor (outside our control) which didn’t seem to explain the real world. If technology was a free-floating ever-present factor, equally available across the world, why did some nations or regions do far better or worse than others? (more…)

Indiana, center of the 5G wireless world (at least for today)

About 18 months ago, wireless small cells started popping up all around Indianapolis. The one pictured above is about a half-mile from my house. In addition to these suburban versions, built by one large mobile carrier, a different mobile carrier built a network of 83 small cells in downtown Indy. These small cells are a key architectural facet of the next generation of wireless broadband, known as 5G, and over the next few years we’ll build hundreds of thousands of them across the country. This “densification” of mobile networks will expand coverage and massively boost speeds, responsiveness, and reliability. Our smartphones will of course benefit, but so will a whole range of other new devices and applications.

Building hundreds of thousands of these cells, however, will require lots of investment. A common estimate is $275 billion for the U.S. It will also require the cooperation of states and localities to speed the permitting to place these cells on lampposts, buildings, utility poles, and other rights of way. And this is where Indiana has led the way, with a decade’s worth of pro-broadband policy and, more recently, legislation that’s already encouraged the deployment of more than 1,000 small cells across the state.

Today, Brendan Carr, one of five commissioners of the Federal Communications Commission, visited Indiana to highlight our state’s early successes – and to lay out the next steps in the FCC’s program to expand 5G as quickly as possible. Carr described the key components of his plan, to be voted on at the Commission’s September 25 meeting. The prospective Order:

- Implements long-standing federal law that bars municipal rules that have the effect of prohibiting deployment of wireless service

- Allows municipalities to charge fees for reviewing small cell deployments when such fees are limited to recovering the municipalities’ costs, and provides guidance on specific fee levels that would comply with this standard

- Requires municipalities to approve or disapprove applications to attach small cells to existing structures within 60 days and applications to build new small cell poles within 90 days

- Places modest guardrails on other municipal rules that may prohibit service while reaffirming localities’ traditional roles in, for example, reasonable aesthetic reviews

Carr emphasized that this new framework, which will bar excessive fees, will help small towns and communities better compete for infrastructure and capital. We know that wireless firms have to build networks in large “must have” markets such as New York and San Francisco, where millions of Americans live and work. High fees and onerous permitting obstacles, however, are particularly hard on smaller communities – often discouraging investment in these non-urban geographies. This new framework, therefore, is yet another important component of closing the “digital divide.”

Here’s video of Carr’s talk at the Statehouse.

Energy Market of 2030: The End of Carbon Fuels?

See our contribution, with 15 others, to an International Economy symposium looking ahead to the energy market of 2030: The End of Carbon Fuels? Here was our contribution:

The dramatic reduction in U.S. carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions over the last decade is, paradoxically, the result of the massively increased use of a fossil fuel—natural gas. The shale technology revolution produced so much low-cost natural gas, and replaced so much coal, that U.S. emissions from electricity generation have fallen to levels not seen since the late 1980s.

Over time, electric vehicles—and later, autonomous ones—could reduce the need for oil. But natural gas will only rise in importance as the chief generator of inexpensive and reliable electricity.

The Energy Information Administration projects that fossil fuels will still represent 81 percent of total energy consumption in 2030. Natural gas, EIA estimates, will be the largest source of electricity, generating between 50 percent and 100 percent more than renewables.

Sure, but don’t technology revolutions often surprise even the smartest prognosticators? Renewables have indeed been growing from a tiny base, and some believe solar power is poised for miraculous gains.

Despite real advances in solar power and battery storage, however, these technologies don’t follow a Moore’s law path. Solar will grow, but we won’t solve solar’s (nor wind’s) fundamental intermittency and thus unreliability challenges by 2030. Nor can we avoid their voracious appetite for the earth’s surface, a fundamental scarcity which environmentalists and conservationists of all stripes should hope to preserve. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos even dreams of a day when we move much heavy industry into space to preserve the earth’s surface for human enjoyment.

But shouldn’t we pay extra in land area (and dollars) today to avoid CO2’s climate effects tomorrow? Fear not. The latest estimates of the climate’s CO2 sensitivity suggest any warming over the next century will be just half of previous estimates and, therefore, a net benefit to humanity and the earth. Satellites show us that CO2 greens the planet.

Economic growth is the most humane policy today, and it opens up frontiers of innovation, including new energy technologies. Premature anti-CO2 policies can actually boost CO2 emissions, as happened in Germany, where ill-advised wind and solar mandates (and also nuclear decommissionings) so decimated the energy grid that the nation had to quickly build new coal plants. New nuclear technologies are technologically superior to solar and wind but remain irrationally unpopular politically. Emitting more CO2 today may thus accelerate the date when economical, non-CO2 emitting technologies generate most of our power.

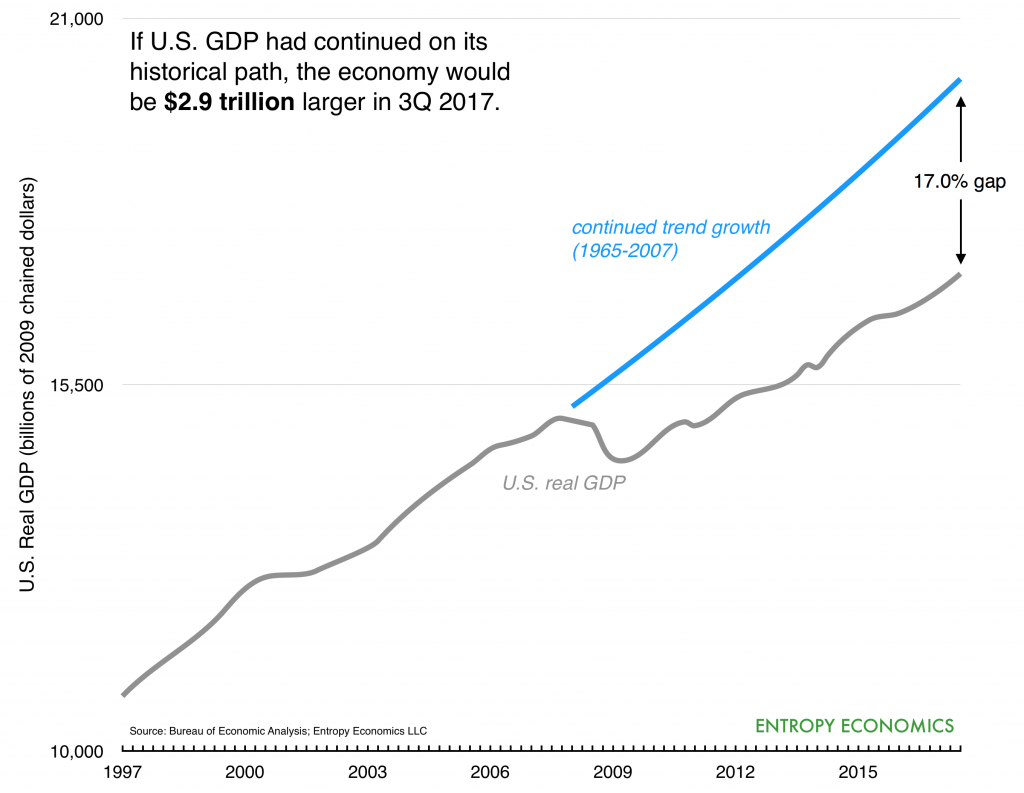

What a coincidence! Maybe better policy can lead to faster growth.

It’s fascinating to see those commentators and economists, who insisted for nearly a decade that 2% was the best the U.S. could do, grapple with the apparent uptick in economic growth and improving labor markets. Secular stagnation, technological stagnation, financial recessions are different, better get used to the “new normal” – these were the explanations (excuses?) for the failure of the economy to recover from the Panic of 2008. Millions of Americans had permanently dropped out of the labor market, robots were taking their jobs, or (paradoxically) technology was impotent, an aging population meant the U.S. would never grow faster than 2% again, and a global dearth of demand meant the economy would be stuck for many years to come. Wages for most workers weren’t growing, and inequality increased because of monopolies or greed or . . . whatever – anything but a failure of policy to encourage growth. Only bigger government could restart the stagnating secular engine, but even then, don’t expect too much.

All of the sudden, however, we’re hearing stories of tight labor markets, and 2017 will likely exhibit the fastest growth for a calendar year since 2006. We think there are three key reasons for the 2017 uptick: (1) an abrupt cessation of the anti-growth policy avalanche; (2) dramatic policy improvements, such as wide-ranging regulatory reforms and a major tax overhaul; and (3) the beginnings of a tech-led productivity freshening.

As Adam Ozimek (@ModeledBehavior) writes:

This story is both very happy but also does make me mad, because I think there hasn’t been a reckoning. This mistake was in a sense bigger than failing to predict the Great Recession, because it was more of an unforced error. And there is no similar push for economist rethinking

— Adam Ozimek (@ModeledBehavior) January 14, 2018

It’s refreshing to hear a mainstream economist call out the massive failure of the last decade – a devastating “growth gap” that we’ve been railing against for many years (also, e.g., Beyond the New Normal; Technology and the Growth Imperative; Uncage the Economy; etc.). It’s more than a little odd, however, that Ozimek singles out for criticism several economists who were arguing that the economy could have been growing much faster, if we’d let it, and were suggesting policies that could help boost employment. Shouldn’t he specifically call out the stagnation apologists instead? Isn’t the “giant mistake,” as Ozimek calls it, the insistence the economy was growing as fast as possible and the arguments that diverted attention from bad policy, unnecessarily slow growth, stagnating wages, and a huge drop in employment?

Many stagnationists are now searching for possible explanations for the nascent uptick. Some are looking toward a possible resurgence of technology and the idea that productivity growth might improve from its decade-long drop. Larry Summers says the apparent uptick is merely a “sugar high” that won’t last. But you can see many of the stagnationists labor to avoid any acknowledgement that better policy might be at the heart of economic improvement. (By the way, I’m thrilled that our tech-led “Productivity Boom” thesis is getting this attention. The recent converts, however, seem to say that a new tech-boom is now inevitable, when just months or weeks ago they said tech was over. I think the policy improvements of 2017 will accelerate technological innovation in many lagging sectors.)

It’s too early to know whether these encouraging signs are the beginning of a long-term growth acceleration. But it’s good to see lots of people finally acknowledge the depth of the growth gap and the higher innovative potential of the American economy.

Tax reform can boost technology, productivity . . . and pay

Our take, in The Hill, on the prospects for tax reform and its effects on investment, productivity, and wages.

Tax reform can boost technology, productivity and, yes, your wage

by Bret Swanson | The Hill | December 14, 2017

What’s the link between robots, artificial intelligence and tax reform? We’ve been debating whether new technologies can ignite a productivity resurgence or whether tech has lost its potency; whether increased productivity will benefit workers or eliminate jobs altogether.

Understanding these relationships can help show why tax reform might boost all three — technology, productivity, and pay.

One of the most serious anti-tax reform claims is that it won’t help the average worker. Investment, productivity and growth, this argument says, are accruing mostly to the fortunate few. So, even if we could boost those top-line metrics, we may not be doing much for the typical American. (more…)

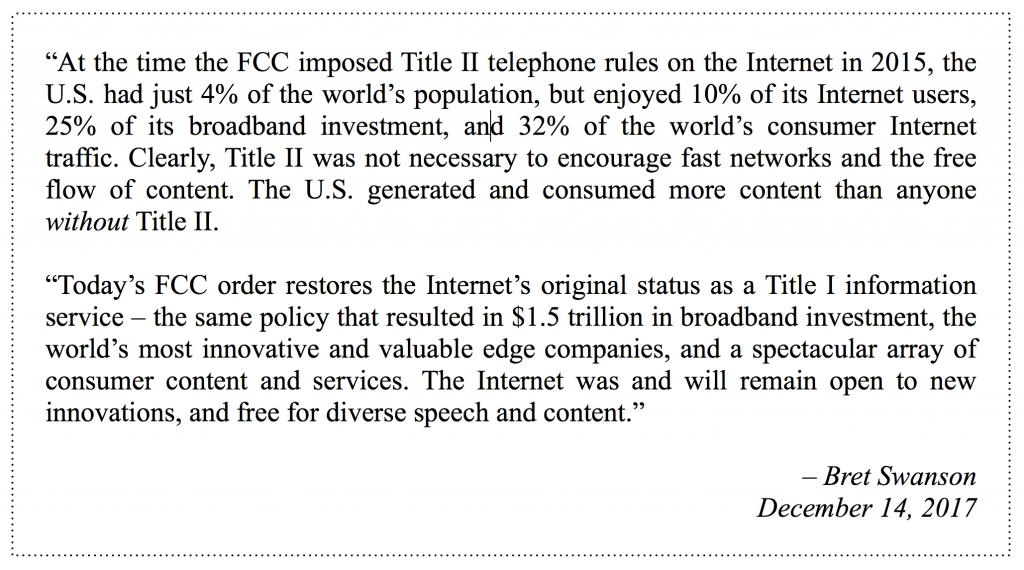

Statement on “Restoring Internet Freedom”

Lots of people are asking what I think about today’s FCC vote to roll back the 2015 Title telephone regulations for the Internet, and restore the Internet as an “information service.” So here’s a summary of my view:

“Net Neutrality and Antitrust,” a House committee hearing

On Wednesday, a House Judiciary subcommittee heard testimony on the potential for existing general-purpose antitrust, competition, and consumer protection laws to police the Internet. Until the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) issued its 2015 Title II Order, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) oversaw these functions. The 2015 rule upended decades worth of successful policy, but now that the new FCC is likely to return the Internet to its original status as a Title I information service, Title II advocates are warning that general purpose law and the FTC are not equipped to deal with the Internet. They’re also hoping that individual states enter the Internet regulation game. I think they are wrong on both counts.

In fact, it’s more important than ever that we govern the sprawling Internet with general purpose laws and economic principles, not the outdated, narrow, vertical silos of a 1934 monopoly telephone law. And certainly not a patchwork of conflicting state laws. The Internet is not just “modernized telephone wires.” It is a broad and deep ecosystem of communications and computing infrastructure; vast, nested layers of software, applications, and content; and increasingly varied services connecting increasingly diverse end-points and industries. General purpose rules are far better suited to this environment than the 80-year old law written to govern one network, built and operated by one company, to deliver one service.

Over the previous two decades of successful operation under Title I, telecom, cable, and mobile firms in the U.S. invested a total of $1.5 trillion in wired and wireless broadband networks. But over the last two years, since the Title II Order, the rate of investment has slowed. In 2014, the year before the Title II Order, U.S. broadband investment was $78.4 billion, but in 2016 that number had dropped by around 3%, to $76 billion. In the past, annual broadband investment had only dropped during recessions.

This is a concern because massive new investments are needed to fuel the next waves of Internet innovation. If we want to quickly and fully deploy new 5G wireless networks over the coming 15 years, for example, we need to extend fiber optic networks deeper into neighborhoods and more broadly across the nation in order to connect millions of new “small cells” that will not only deliver ever more video to our smartphones but also enable autonomous vehicles and the Internet of Things. It’s a project that may cost $250-300 billion, but it would happen far more slowly under Title II, and many marginal investments in marginal geographies might never happen at all.

At the hearing, FTC Commissioner Terrell McSweeny defended the 2015 Title II order, which poached many oversight functions from her own agency. Her reasoning was odd, however. She said that we needed to radically change policy in order to preserve the healthy results of previously successful policy. She said the Internet’s success depended on its openness, and we could sustain that openness only by applying the old telephone regulations, for the first time, to the Internet.

This gets things backwards. In our system, we usually intervene in markets and industries only if we demonstrate both serious and widespread market failures and if we think a policy can deliver clear improvements compared to its possible downside. In other words, the burden is on the government to prove harm and that it can better manage an industry. The demonstrable success of the Internet made this a tough task for the FCC. In the end, the FCC didn’t perform a market analysis, didn’t show market failures or consumer harm, didn’t show market power, and didn’t perform a cost-benefit analysis of its aggressive new policy. It simply asserted that it knew better how to manage the technology and business of the Internet, compared to engineers and entrepreneurs who had already created one of history’s biggest economic and technical successes.

Commissioner McSweeny also disavowed what had been one of the FTC’s most important new-economy functions and one in which it had developed a good bit of expertise – digital privacy. Under the Title II Order, the FCC snatched from the FTC the power to regulate Internet service providers (ISPs) on matters of digital privacy. Now that the FCC looks to be returning that power to the FTC, however, some states are attempting to regulate Internet privacy themselves. This summer, for example, California legislators tried to impose the Title II Order’s privacy rules on ISPs. Although that bill didn’t pass, you can bet California and other states will be back.

It’s important, therefore, that the FCC reaffirm longstanding U.S. policy – that the Internet is the ultimate form of interstate commerce. Here’s the way we put it in a recent post:

The internet blew apart the old ways of doing things. Internet access and applications are inherently nonlocal services. In this sense, the “cloud” analogy is useful. Telephones used to be registered to a physical street address. Today’s mobile devices go everywhere. Data, services, and apps are hosted in the cloud at multiple locations and serve end users who could be anywhere — likewise for peer-to-peer applications, which connect individual users who are mobile. Along most parameters, it makes no sense to govern the internet locally. Can you imagine 50 different laws governing digital privacy or net neutrality? It would be confusing at best, but more likely debilitating.

The Democratic FCC Chairman Bill Kennard weighed in on this matter in the late 1990s. He was in the middle of the original debate over broadband and argued firmly that high-speed cable modems were subject to a national policy of “unregulation” and should not be swept into the morass of legacy regulation.

In a 1999 speech, he admonished those who would seek to regulate broadband at the local or state level:

“Unfortunately, a number of local franchising authorities have decided not to follow this de-regulatory, pro-competitive approach. Instead, they have begun imposing their own local open access provisions. As I’ve said before, it is in the national interest that we have a national broadband policy. The FCC has the authority to set one, and we have. We have taken a de-regulatory approach, an approach that will let this nascent industry flourish. Disturbed by the effect that the actions of local franchising authorities could have on this policy and on the deployment of broadband, I have asked our general counsel to prepare a brief to be filed in the pending Ninth Circuit case so we can explain to the court why it’s important that we have a national policy.”

In the coming months, the FCC will likely reclassify the internet as a Title I information service. In addition to freeing broadband and mobile from the regulatory straitjacket of the 2015 Title II Order, this will also return oversight responsibility for digital privacy to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), its natural home. The FTC has spent the last decade developing rules governing this important and growing arena and has enforced those rules to protect consumers. States’ efforts to impose their own layer of possibly contradictory rules would only confuse consumers and discourage upstart innovators.

As the internet becomes an ever more important component of all that we do, as its complexity spreads, and as it touches more parts of the economy, this principle will only become more important. Yes, there will be legitimate debates over just where to draw the boundaries. As the internet seeps further into every economic and social act, this does not mean that states will lose all power to govern. But to the extent that Congress, the FCC, and the FTC have the authority to protect the free flow of internet activity against state-based obstacles and fragmentation, they should do so. In its coming order, the FCC should reaffirm the interstate nature of these services.

A return to the Internet’s original status as a Title I information service, protected from state-based fragmentation, merely extends and strengthens the foundation upon which the U.S. invented and built the modern information economy.

The $12-million iPhone

Several years ago, I had a bit of fun estimating how much an iPhone would have cost to make in the 1990s. The impetus was a story making the rounds on the web. A journalist had found a full-page newspaper ad from RadioShack dating back to 1991. He was rightly amazed that all 13 of the advertised electronic gadgets — computer, camcorder, answering machine, cordless phone, etc. — were now integrated into a single iPhone. The cost of those 13 gadgets, moreover, summed to more than $3,000. Wow, he enthused, most of us now hold $3,000 worth of electronics in the palm of our hand.

I saluted the writer’s general thrust but noted that he had wildly underestimated the true worth of our modern handheld computers. In fact, the computing power, data storage capacity, and communications bandwidth of an iPhone in 2014 would have cost at least $3 million back in 1991. He had underestimated the pace of advance by three orders of magnitude (or a factor of 1,000).

Well, in a recent podcast, our old friend Richard Bennett of High Tech Forum brought up the $3 million iPhone 5 from 2014, so I decided to update the estimate. For the new analysis, I applied the same method to my own iPhone 7, purchased in the fall of 2016 — 25 years after the 1991 RadioShack ad. continue reading . . .

Why productivity slowed . . . and why it’s about to soar.

I enjoyed discussing technology’s impact on growth and employment with David Beckworth and Michael Mandel on David’s Macro Musings podcast.

Full speed ahead on the internet

Here’s a brief statement on today’s action at the Federal Communications Commission, where the agency will begin a rule-making to reverse Title II regulation of the Internet and ask how best to protect its freedom and openness.

The Internet has always been open and free, and the successful results were clear for all to see. The imposition of Title II regulation on the Internet in 2015 was unnecessary, illegal, and foolish. Title II was a speed bump that, if allowed to remain, could have grown into a giant road-block to Internet innovation. Fortunately, Chairman Ajit Pai and the FCC today begin the process of returning to the simple rules that for decades fostered Internet investment and entrepreneurship and led to the historically successful digital economy.

The next waves of Internet innovation will bring the amazing power of the digital economy to the physical economy, promising widespread economic benefits. If we want to take the next step, to encourage infrastructure investment and innovation for decades to come, Congress could codify a pro-innovation, pro-consumer approach that would keep the Internet free and open without harmful bureaucratic control.

– Bret Swanson

Robots on TV

See brief interview on Fox Business this morning discussing our “Robots Will Save the Economy” op-ed from The Wall Street Journal.