We’re excited to share this new research, conducted with Michael Mandel, and commissioned by the Technology CEO Council. Here’s the Executive Summary:

We’re excited to share this new research, conducted with Michael Mandel, and commissioned by the Technology CEO Council. Here’s the Executive Summary:

Executive Summary

The Information Age is not over. It has barely begun.

● The diffusion of information technology into the physical industries is poised to revive the economy, create jobs, and boost incomes. Far from nearing its end, the Information Age may give us its most powerful and widespread economic benefits in the years ahead. Aided by improved public policy focused on innovation, we project a significant acceleration of productivity across a wide array of industries, leading to more broad-based economic growth.

● The 10-year productivity drought is almost over. The next waves of the information revolution—where we connect the physical world and infuse it with intelligence—are beginning to emerge. Increased use of mobile technologies, cloud services, artificial intelligence, big data, inexpensive and ubiquitous sensors, computer vision, virtual reality, robotics, 3D additive manufacturing, and a new generation of 5G wireless are on the verge of transforming the traditional physical industries—healthcare, transportation, energy, education, manufacturing, agriculture, retail, and urban travel services.

● At 2.7%, productivity growth in the digital industries over the last 15 years has been strong.

● On the other hand, productivity in the physical industries grew just 0.7% annually, leading to anemic economic growth over the last decade.

● The digital industries, which account for around 25% of U S private-sector employment and 30% of private-sector GDP, make 70% of all private-sector investments in information technology. The physical industries, which are 75% of private-sector employment and 70% of private-sector GDP, make just 30% of the investments in information technology.

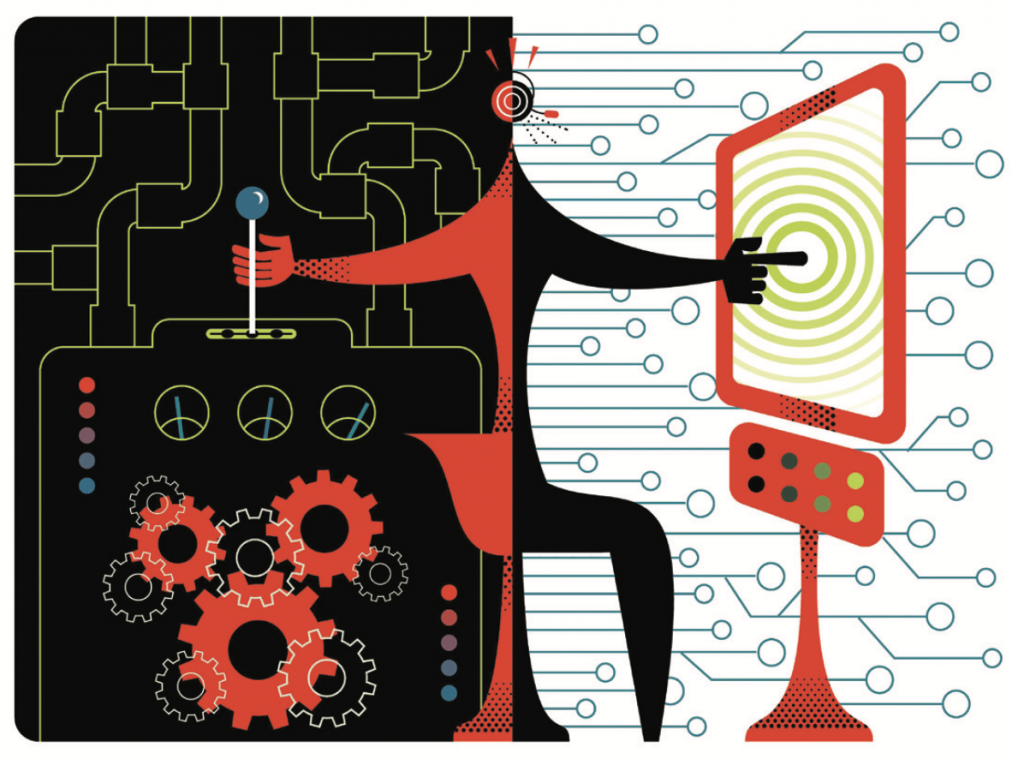

● This “information gap” is a key source of recent economic stagnation and the productivity paradox, where many workers seem not to have benefited from apparent rapid technological advances. Three-quarters of the private sector—the physical economy—is operating well below its potential, dragging down growth and capping living standards.

● In particular, the crucial manufacturing sector, outside the computer and electronics industry, has barely boosted its capital stock of IT equipment and software over the past 15 years. Not surprisingly, productivity growth in manufacturing has slowed to a crawl in recent years.

● Information technologies make existing processes more efficient. More importantly, however, creative deployment of IT empowers entirely new business models and processes, new products, services, and platforms. It promotes more competitive differentiation. The digital industries have embraced and benefited from scalable platforms, such as the Web and the smartphone, which sparked additional entrepreneurial explosions of variety and experimentation. The physical industries, by and large, have not. They have deployed comparatively little IT, and where they have done so, it has been focused on efficiency, not innovation and new scalable platforms. That’s about to change.

● Healthcare, energy, and transportation, for example, are evolving into information industries Smartphones and wearable devices will make healthcare delivery and data collection more effective and personal, while computational bioscience and customized molecular medicine will radically improve drug discovery and effectiveness. Artificial intelligence will assist doctors, and robots will increasingly be used for surgery and eldercare. The boom in American shale petroleum is largely an information technology phenomenon, and it’s just the beginning. Autonomous vehicles and smart traffic systems, meanwhile, will radically improve personal, public, and freight transportation in terms of both efficiency and safety, but they also will create new platforms upon which entirely new economic goods can be created.

● Manufacturing may be on the cusp of transformation—not just by robotics and 3D printing, but by the emergence of smart manufacturing more broadly: a fundamental rethinking of the production and design processes that substantially boost productivity and demand. That, in turn, could create a new set of manufacturing-related jobs and allow American factories to compete more effectively against low-wage rivals.

● Far from a jobless future, a more productive physical economy will make American workers more valuable and employable. It also will free up resources to spend on new types of goods and services. Artificial intelligence and robots will not only perform many unpleasant and super-human tasks but also will complement our most human capabilities and make workers more productive than ever. Humans equipped with boundless information, machine intelligence, and robot strength will create many new types of jobs.

● Employment growth in the digital sector has modestly outpaced employment growth in the physical sector, despite the big edge in productivity growth for digital industries. This suggests that we can both achieve higher living standards and create good new jobs. The notion that automation is the key enemy of jobs is wrong. Over the medium and long terms, productivity is good for employment.

● How much could these IT-related investments add to economic growth? Our assessment, based on an analysis of recent history, suggests this transformation could boost annual economic growth by 0.7 percentage points over the next 15 years. That may not sound like much, but it would add $2.7 trillion to annual U.S. economic output by 2031, in 2016 dollars. Wages and salary payments to workers would increase by a cumulative $8.6 trillion over the next 15 years. Federal revenues over the period would grow by a cumulative $3.9 trillion, helping to pay for Social Security and Medicare. State and local revenues would rise by a cumulative $1.9 trillion, all without increasing the tax share of GDP.

● Expanding the information revolution to the physical industries will require an entrepreneurial mindset—in industry and in government—to deploy information technology in new ways and reorganize firms and sectors to exploit the power of IT. Some of these technological transformations are already underway. Public policy, however, will either retard or accelerate the diffusion of information into the physical industries. Better or worse policy will, in significant part, determine the rate at which more people enjoy the miraculous benefits of rapid innovation, both as workers and consumers.

● Better tax policy, for example, can encourage domestic investment and the allocation of capital into more cutting-edge projects and firms. Closing the information gap also will demand the ability of regulators in the physical industries—from the Food and Drug Administration to the Department of Transportation, and every agency in between—to embrace innovation and technological change. Mobilizing information to dramatically improve education and training is imperative if we want our citizens to fully leverage and benefit from these emerging opportunities. Encouraging investment in communications networks, which are the foundation of most of these new capabilities, is also a crucial priority. The free flow of capital, goods, services, and data around the world is as essential as ever to innovation and productivity.

● Launching this new productivity boom thus demands a new, pro-innovation focus of public policy.

Read the entire report.