“A revival of economic growth in the U.S. and around the world will, to a not insignificant degree, depend on the successful deployment of the next generation of wireless technology.

“A revival of economic growth in the U.S. and around the world will, to a not insignificant degree, depend on the successful deployment of the next generation of wireless technology.

“The Internet’s first few chapters transformed entertainment, news, telephony, and finance — in other words, the existing electronic industries. Going forward, however, the wireless Internet will increasingly reach out to the rest of the economy and transform every industry, from transportation to education to health care.

“To drive and accommodate this cascading wireless boom, we will need wireless connections that are faster, greater in number, and more robust, widespread, diverse, and flexible. We will need a new fifth generation, or 5G, wireless infrastructure. 5G will be the foundation of not just the digital economy but increasingly of the physical economy as well.”

That’s how I began a recent column summarizing my research on the potential for technology to drive economic growth. 5G networks will not only provide an additional residential broadband option. 5G will also be the basis for the Internet of Things (IoT), connected cars and trucks, mobile and personalized digital health care, and next generation educational content and tools. The good news is that Indiana is already poised to lead in 5G. AT&T, for example, has announced that Indianapolis is one of two sites nationwide that will get a major 5G trial. And Verizon is already deploying “small cells” – a key component of 5G networks – across the metro area, including in my hometown of Zionsville (see photo).

Small cell lamppost in Zionsville, Indiana.

If Indiana is to truly lead in 5G, and all the next generation services, however, it will need to take the next step. That means modest legislation that makes it as easy as possible to deploy these networks. Streamlining the permitting process for small cells will not only encourage investment and construction jobs as we string fiber optics and erect small cells. It will also mean Indiana will be among the first to enjoy the fast and ubiquitous connectivity that will be the foundation of nearly every industry going forward. In many ways, 5G is the economic development opportunity of the next decade.

There is legislation currently moving in the Indiana General Assembly that could propel Indiana along its already favorable 5G path. Sponsored by Sen. Brandt Hershman, SB 213 is a common sense and simple way to encourage investment in these networks, and the multitude of services that will follow.

The great news is that 5G is one of the few economic and Internet policy issues that enjoys widespread bipartisan support. The current FCC chairman Ajit Pai supports these streamlining polices, but so did the former Democratic chairman Tom Wheeler:

The nature of 5G technology doesn’t just mean more antenna sites, it also means that without such sites the benefits of 5G may be sharply diminished. In the pre-5G world, fending off sites from the immediate neighborhood didn’t necessarily mean sacrificing the advantages of obtaining service from a distant cell site. With the anticipated 5G architecture, that would appear to be less feasible, perhaps much less feasible.

I have no doubt other states will copy Indiana, once they see what we’ve done – or leap ahead of us, if we don’t embrace this opportunity.

Here are a few of our reports, articles, and podcasts on 5G:

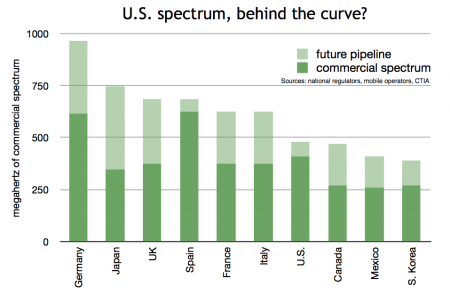

Imagining the 5G Wireless Future: Apps, Devices, Networks, Spectrum – Entropy Economics report, November 2016

5G Wireless Is a Platform for Economic Revival – summary of report in The Hill, November 2016

5G and the Internet of Everything – podcast with TechFreedom, December 2016

Opening the 5G Wireless Frontier – article in Computerworld, July 2016

– Bret Swanson