Later this week the FCC will accept the first round of comments in its “Open Internet” rule making, commonly known as Net Neutrality. Never mind that the Internet is already open and it was never strictly neutral. Openness and neutrality are two appealing buzzwords that serve as the basis for potentially far reaching new regulation of our most dynamic economic and cultural sector – the Internet.

I’ll comment on Net Neutrality from several angles over the coming days. But a terrific essay by Berkeley’s Jaron Lanier impelled me to begin by summarizing some of the big meta-arguments that have been swirling the last few years and which now broadly define the opposing sides in the Net Neutrality debate. After surveying these broad categories, I’ll get into the weeds on technology, business, and policy.

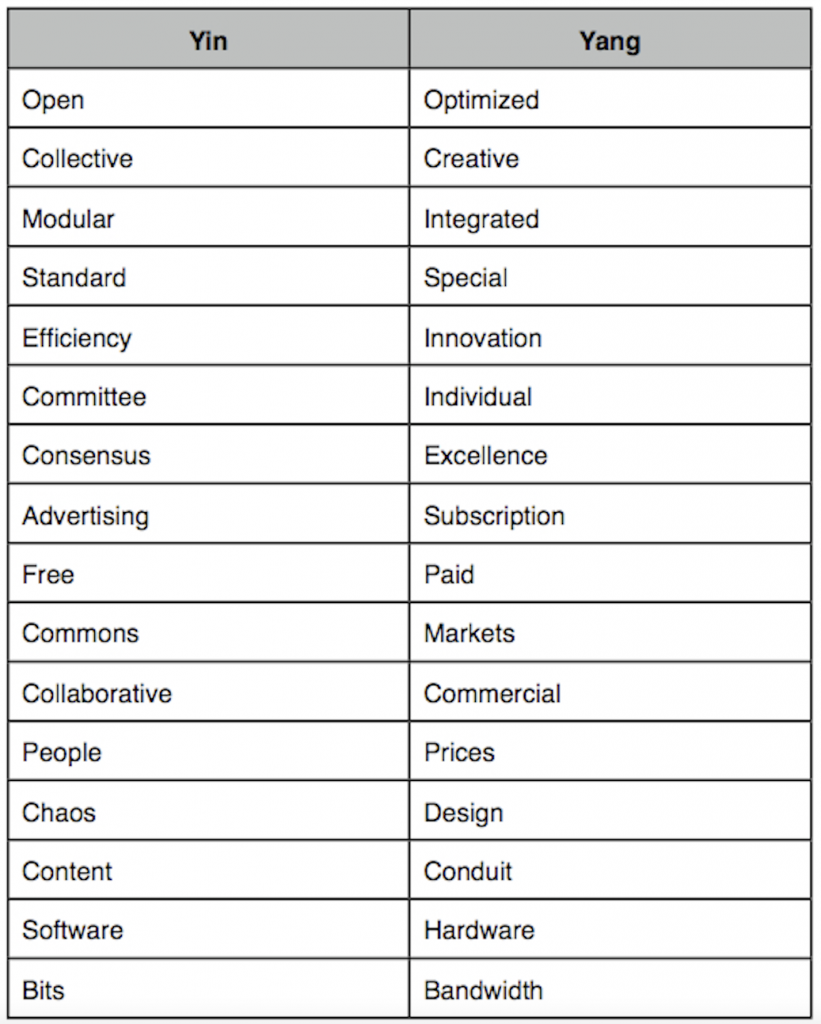

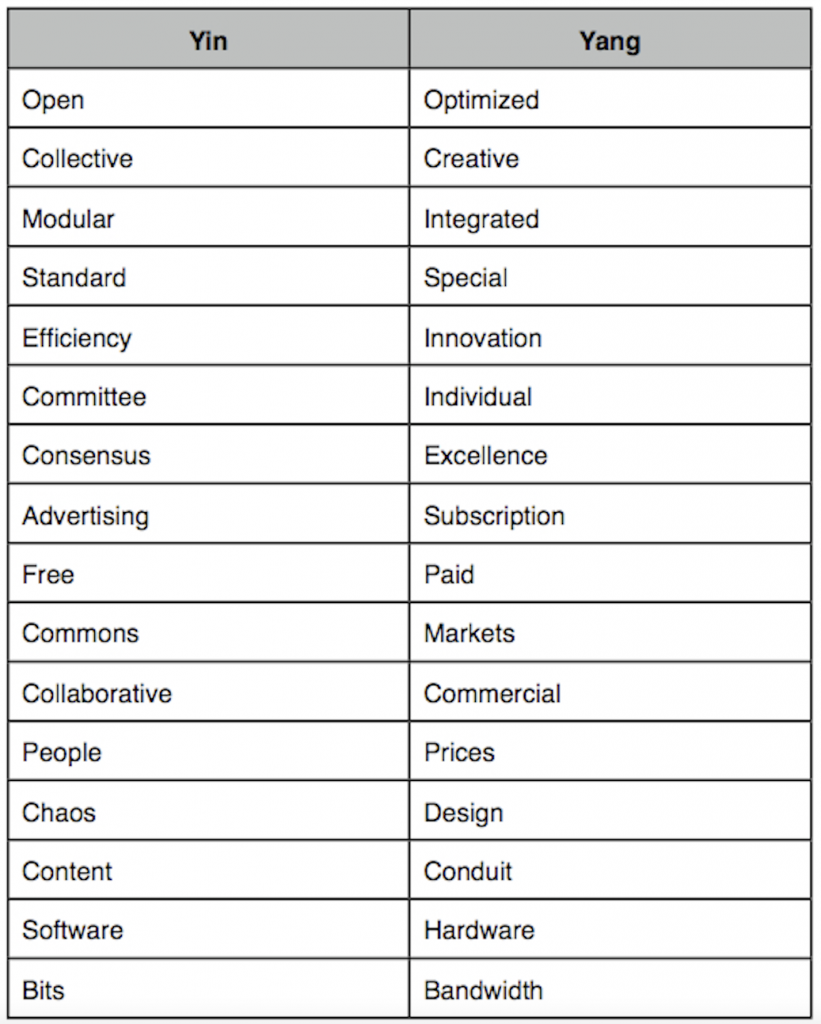

The thrust behind Net Neutrality is a view that the Internet should conform to a narrow set of technology and business “ideals” – “open,” “neutral,” “non-discriminatory.” Wonderful words. Often virtuous. But these aren’t the only traits important to economic and cultural systems. In fact, Net Neutrality sets up a false dichotomy – a manufactured war – between open and closed, collaborative versus commercial, free versus paid, content versus conduit. I’ve made a long list of the supposed opposing forces. Net Neutrality favors only one side of the table below. It seeks to cement in place one model of business and technology. It is intensely focused on the left-hand column and is either oblivious or hostile to the right-hand column. It thinks the right-hand items are either bad (prices) or assumes they appear magically (bandwidth).

We skeptics of Net Neutrality, on the other hand, do not favor one side or the other. We understand that there are virtues all around. Here’s how I put it on my blog last autumn:

Suggesting we can enjoy Google’s software innovations without the network innovations of AT&T, Verizon, and hundreds of service providers and technology suppliers is like saying that once Microsoft came along we no longer needed Intel.

No, Microsoft and Intel built upon each other in a virtuous interplay. Intel’s microprocessor and memory inventions set the stage for software innovation. Bill Gates exploited Intel’s newly abundant transistors by creating radically new software that empowered average businesspeople and consumers to engage with computers. The vast new PC market, in turn, dramatically expanded Intel’s markets and volumes and thus allowed it to invest in new designs and multi-billion dollar chip factories across the globe, driving Moore’s law and with it the digital revolution in all its manifestations.

Software and hardware. Bits and bandwidth. Content and conduit. These things are complementary. And yes, like yin and yang, often in tension and flux, but ultimately interdependent.

Likewise, we need the ability to charge for products and set prices so that capital can be rationally allocated and the hundreds of billions of dollars in network investment can occur. It is thus these hard prices that yield so many of the “free” consumer surplus advantages we all enjoy on the Web. No company or industry can capture all the value of the Web. Most of it comes to us as consumers. But companies and content creators need at least the ability to pursue business models that capture some portion of this value so they can not only survive but continually reinvest in the future. With a market moving so fast, with so many network and content models so uncertain during this epochal shift in media and communications, these content and conduit companies must be allowed to define their own products and set their own prices. We need to know what works, and what doesn’t.

When the “network layers” regulatory model, as it was then known, was first proposed back in 2003-04, my colleague George Gilder and I prepared testimony for the U.S. Senate. Although the layers model was little more than an academic notion, we thought then this would become the next big battle in Internet policy. We were right. Even though the “layers” proposal was (and is!) an ill-defined concept, the model we used to analyze what Net Neutrality would mean for networks and Web business models still applies. As we wrote in April of 2004:

Layering proponents . . . make a fundamental error. They ignore ever changing trade-offs between integration and modularization that are among the most profound and strategic decisions any company in any industry makes. They disavow Harvard Business professor Clayton Christensen’s theorems that dictate when modularization, or “layering,” is advisable, and when integration is far more likely to yield success. For example, the separation of content and conduit – the notion that bandwidth providers should focus on delivering robust, high-speed connections while allowing hundreds of millions of professionals and amateurs to supply the content—is often a sound strategy. We have supported it from the beginning. But leading edge undershoot products (ones that are not yet good enough for the demands of the marketplace) like video-conferencing often require integration.

Over time, the digital and photonic technologies at the heart of the Internet lead to massive integration – of transistors, features, applications, even wavelengths of light onto fiber optic strands. This integration of computing and communications power flings creative power to the edges of the network. It shifts bottlenecks. Crystalline silicon and flawless fiber form the low-entropy substrate that carry the world’s high-entropy messages – news, opinions, new products, new services. But these feats are not automatic. They cannot be legislated or mandated. And just as innovation in the core of the network unleashes innovation at the edges, so too more content and creativity at the edge create the need for ever more capacity and capability in the core. The bottlenecks shift again. More data centers, better optical transmission and switching, new content delivery optimization, the move from cell towers to femtocell wireless architectures. There is no final state of equilibrium where one side can assume that the other is a stagnant utility, at least not in the foreseeable future.

I’ll be back with more analysis of the Net Neutrality debate, but for now I’ll let Jaron Lanier (whose book You Are Not a Gadget was published today) sum up the argument:

Here’s one problem with digital collectivism: We shouldn’t want the whole world to take on the quality of having been designed by a committee. When you have everyone collaborate on everything, you generate a dull, average outcome in all things. You don’t get innovation.

If you want to foster creativity and excellence, you have to introduce some boundaries. Teams need some privacy from one another to develop unique approaches to any kind of competition. Scientists need some time in private before publication to get their results in order. Making everything open all the time creates what I call a global mush.

There’s a dominant dogma in the online culture of the moment that collectives make the best stuff, but it hasn’t proven to be true. The most sophisticated, influential and lucrative examples of computer code—like the page-rank algorithms in the top search engines or Adobe’s Flash—always turn out to be the results of proprietary development. Indeed, the adored iPhone came out of what many regard as the most closed, tyrannically managed software-development shop on Earth.

Actually, Silicon Valley is remarkably good at not making collectivization mistakes when our own fortunes are at stake. If you suggested that, say, Google, Apple and Microsoft should be merged so that all their engineers would be aggregated into a giant wiki-like project—well you’d be laughed out of Silicon Valley so fast you wouldn’t have time to tweet about it. Same would happen if you suggested to one of the big venture-capital firms that all the start-ups they are funding should be merged into a single collective operation.

But this is exactly the kind of mistake that’s happening with some of the most influential projects in our culture, and ultimately in our economy.