John Markoff surveys the near future prospects for Moore’s Law . . . and notes the first mention in print of the transistor, on July 1, 1948.

Dept. of Modern Afflictions

Do you suffer from “network deprivation”? I hope so. I do.

Quote of the Day

“In the end, perhaps the most misleading claim of the peak-oil advocates is that the earth was endowed with only 2 trillion barrels of ‘recoverable’ oil. Actually, the consensus among geologists is that there are some 10 trillion barrels out there. A century ago, only 10 percent of it was considered recoverable, but improvements in technology should allow us to recover some 35 percent — another 2.5 trillion barrels — in an economically viable way. And this doesn’t even include such potential sources as tar sands, which in time we may be able to efficiently tap.

“Oil remains abundant, and the price will likely come down closer to the historical level of $30 a barrel as new supplies come forward in the deep waters off West Africa and Latin America, in East Africa, and perhaps in the Bakken oil shale fields of Montana and North Dakota. But that may not keep the Chicken Littles from convincing policymakers in Washington and elsewhere that oil, being finite, must increase in price.”

— Michael Lynch, New York Times, August 24, 2009

Quote of the Day

“When George W. Bush nominated Ben Bernanke to be Federal Reserve Chairman in late 2005, we wrote that there was ‘at least rough justice’ in the fact that Mr. Bernanke would have to clean up a monetary bubble that he had helped to create. Alas, that was truer than even we feared, and yesterday President Obama rewarded Mr. Bernanke for his efforts by nominating him for a second four-year term.

“One request: This time around, could he make the mess and clean-up a little less bloody?

“A striking fact of the last two years of financial trouble is how accountability has differed in the public and private spheres. On Wall Street and across the country, decades-old firms have failed, fortunes have vanished, and some former captains of finance face jail or fines. In Washington, meanwhile, most regulators and Members of Congress remain on the job, often with enhanced power.”

— The Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2009

Agreeing with Kessler

After challenging Andy Kessler over the Google Voice-Apple-AT&T dustup, I should point out some areas of agreement.

Andy writes:

Some might say it is time to rethink our national communications policy. But even that’s obsolete. I’d start with a simple idea. There is no such thing as voice or text or music or TV shows or video. They are all just data.

Right, all these markets and business models in hardware, software, and content — core network, edge network, data center, storage, content delivery, operating system, browser, local software, software as a service (SAS), professional content, amateur content, advertising, subscriptions, etc. — are fusing via the Internet. Or at least they overlap in so many areas and at any moment are on the verge of converging in others, that any attempt to parse them into discreet sectors to be regulated is mostly futile. By the time you make up new categories, the categories change.

Which naturally applies to one of the most contentious topics in Net policy:

Competition brings de facto network neutrality and open access (if you don’t like one service blocking apps, use another), thus one less set of artificial rules to be gamed.

Exactly. Net Neutrality could be an unworkably complex and rigid intrusion into this highly dynamic space. Better to let companies compete and evolve.

Kessler concludes:

Data is toxic to old communications and media pipes. Instead, data gains value as it hops around in the packets that make up the Internet structure. New services like Twitter don’t need to file with the FCC.

And new features for apps like Google Voice are only limited by the imagination.

The Internet is disrupting communications companies. Although yesterday I defended the service providers, who are also the key investors in all-important Net infrastructure, it is true their legacy business models are under assault from the inexorable forces of quantum technologies. Web video assaults the cable companies’ discrete channel line-ups. Big bandwidth banished “long distance” voice and, as Kessler says, will continue disrupting voice calling plans. On the other hand, the robust latency and jitter requirements of voice and video, and the realities of cybersecurity will continue to modify the generalized principle that bits are bits.

Even if we can see where things are going — more openness, more modularity, more “bits are bits” — we can’t for the most part mandate these things by law. We have to let them happen. And in many cases, as with the Apple-AT&T iPhone, it was an integrated offering (the exclusive handset arrangement) that yielded an unprecedented unleashing of a new modular mobile phone arena. Those 100,000 new “apps” and a new, open Web-based mobile computing model. Integration and modularity are in constant tension and flux, building off one another, pulling and pushing on one another. Neither can claim ultimate virtue. We have to let them slug it out.

As I wrote yesterday, innovation yin and yang.

Quote of the Day

“The flow of capital away from the U.S. is broad, deep and long-term. Investors can buy 20-year debt denominated in Brazilian reals or Chinese yuan, a monumental shift in the allocation of long-term capital. U.S. companies are shifting operations offshore in order to build and innovate more profitably. Meanwhile, the U.S. government is trapping billions of tech dollars — the lifeblood of innovation — offshore through an excessive repatriation tax. This is blocking much-needed industry consolidation, because an acquirer is forced to pay for the offshore cash without getting access to it.”

— David Malpass, August 20, 2009

Innovation Yin and Yang

There are two key mistakes in the public policy arena that we don’t talk enough about. They are two apparently opposite sides of the same fallacious coin.

Call the first fallacy “innovation blindness.” In this case, policy makers can’t see the way new technologies or ideas might affect, say, the future cost of health care, or the environment. The result is a narrow focus on today’s problems rather than tomorrow’s opportunities. The orientation toward the problem often exacerbates it by closing off innovations that could transcend the issue altogether.

The second fallacy is “innovation assumption.” Here, the mistake is taking innovation for granted. Assume the new technology will come along even if we block experimentation. Assume the entrepreneur will start the new business, build the new facility, launch the new product, or hire new people even if we make it impossibly expensive or risky for her to do so. Assume the other guy’s business is a utility while you are the one innovating, so he should give you his product at cost — or for free — while you need profits to reinvest and grow.

Reversing these two mistakes yields the more fruitful path. We should base policy on the likely scenario of future innovation and growth. But then we have to actually allow and encourage the innovation to occur.

All this sprung to mind as I read Andy Kessler’s article, “Why AT&T Killed Google Voice.” For one thing, Google Voice isn’t dead . . . but let’s start at the beginning.

Kessler is a successful investor, an insightful author, and a witty columnist. I enjoy seeing him each year at the Gilder/Forbes Telecosm Conference, where he delights the crowd with fast-paced, humorous commentaries on finance and technology. Here, however, Kessler falls prey to the innovation assumption fallacy.

Kessler argues that Google Voice, a new unified messaging application that combines all your phone numbers into one and can do conference calls and call transcripts, is going to overturn the entire world of telecom. Then he argues that Apple and AT&T attempted to kill Google Voice by blocking it as an “app” on Apple’s iPhone App Store. Why? Because Google Voice, according to Kessler, can do everything the telecom companies and Apple can do — better, even. These big, slow, old companies felt threatened to their core and are attempting to stifle an innovation that could put them out of business. We need new regulations to level the playing field.

Whoa. Wait a minute.

Google Voice seems like a nice product, but it is largely a call-forwarding system. I’ve already had call forwarding, simultaneous ring, Web-based voice mail, and other unified messaging features for five years. Good stuff. Maybe Google Voice will be the best of its kind.

There are just all sorts of fun and productive things happening all across the space. It was the very AT&T-Apple-iPhone combo that created “visual voice mail,” which allowed you to see and choose individual messages instead of wading through long queues of unwanted recordings.

But let’s move on to think about much larger issues.

Suggesting we can enjoy Google’s software innovations without the network innovations of AT&T, Verizon, and hundreds of service providers and technology suppliers is like saying that once Microsoft came along we no longer needed Intel. (more…)

Happy birthday, TLF!

The Technology Liberation Front is five today. Go check out these courageous defenders of Internet freedom, of which I am a too-infrequent yet proud comrade-in-arms.

Romer’s transformative “Charter Cities”

Stanford economist Paul Romer has had lots of good ideas over the years. Particularly his ideas about the importance of ideas in the economy. But his “Charter City” idea explored at the recent TED conference is one of the best yet.

Maybe I like it so much because it so closely tracks the concepts offered in my long paper of last August called “Entrepreneurship and Innovation in China – 1978-2008 – Thirty Years of Decentralized Economic Growth”, a follow-on article in The Wall Street Journal, and a previous essay “Breaking Metcalfe’s Law” on the economic importance of the exchange of ideas.

Romer uses China’s “free zones” envisioned by Deng Xiaoping and initially implemented by one Jiang Zemin as the chief example of how his charter cities would work in practice. He explains how they might cut the political-economic Gordian knot of societies too stuck in the past to make obviously needed rule changes that open the floodgates of ideas and entrepreneurship. These were the key themes of my paper.

Also check out this working paper by Romer that surveys the economic growth literature (hat tip: Growthology).

How the Web unleashes unknown intelligences

Watch Tyler Cowen talk about his new book to Will Wilkinson. The book’s title, Create Your Own Economy, sounds like just another self-help business pamphlet. But you’ll see Cowen isn’t talking about business or money at all — at least not directly. His subjects are autism, “neurodiversity,” Adam Smith’s division of labor, and the Internet’s ability to match more people with their highly specific talents and passions. Far from the latest trope that “Google [or the Web] is making us stupid,” Cowen argues the the Web helps a vast variety of previously undiscovered intelligences, or “neuro profiles,” flourish.

Can Microsoft Grasp the Internet Cloud?

See my new Forbes.com commentary on the Microsoft-Yahoo search partnership:

Ballmer appears now to get it. “The more searches, the more you learn,” he says. “Scale drives knowledge, which can turn around and drive innovation and relevance.”

Microsoft decided in 2008 to build 20 new data centers at a cost of $1 billion each. This was a dramatic commitment to the cloud. Conceived by Bill Gates’s successor, Ray Ozzie, the global platform would serve up a new generation of Web-based Office applications dubbed Azure. It would connect video gamers on its Xbox Live network. And it would host Microsoft’s Hotmail and search applications.

The new Bing search engine earned quick acclaim for relevant searches and better-than-Google pre-packaged details about popular health, transportation, location and news items. But with just 8.4% of the market, Microsoft’s $20 billion infrastructure commitment would be massively underutilized. Meanwhile, Yahoo, which still leads in news, sports and finance content, could not remotely afford to build a similar new search infrastructure to compete with Google and Microsoft. Thus, the combination. Yahoo and Microsoft can share Ballmer’s new global infrastructure.

Doom? Or Boom?

Do we really understand just how fast technology advances over time? And the magnitude of price changes and innovations it yields?

Especially in the realm of public policy, we often obsess over today’s seemingly intractable problems without realizing that technology and economic growth often show us a way out.

In several recent presentations in Atlanta and Seattle, I’ve sought to measure the growth of a key technological input — consumer bandwidth — and to show how the pace of technological change in other arenas is likely to continue remaking our world for the better . . . if we let it.

Mirrors, mirror neurons, and the future of the brain

Fascinating stuff from UC-San Diego’s V.S. Ramachandran, who has pioneered the understanding of mirror neurons using almost primitive experiments with store-bought mirrors . . . among many other wonders . . .

Broadband benefit = $32 billion

We recently estimated the dramatic gains in “consumer bandwidth” — our ability to communicate and take advantage of the Internet. So we note this new study from the Internet Innovation Alliance, written by economists Mark Dutz, Jonathan Orszag, and Robert Willig, that estimates a consumer surplus from U.S. residential broadband Internet access of $32 billion. “Consumer surplus” is the net benefit consumers enjoy, basically the additional value they receive from a product compared to what they pay.

Biting the handsets that connect the world

Over the July 4 weekend, relatives and friends kept asking me: Which mobile phone should I buy? There are so many choices.

I told them I love my iPhone, but all kinds of new devices from BlackBerries and Samsungs to Palm’s new Pre make strong showings, and the less well-known HTC, one of the biggest innovators of the last couple years, is churning out cool phones across the price-point and capability spectrum. Several days before, on Wednesday, July 1, I had made a mid-afternoon stop at the local Apple store. It was packed. A short line formed at the entrance where a salesperson was taking names on a clipboard. After 15 minutes of browsing, it was my turn to talk to a salesman, and I asked: “Why is the store so crowded? Some special event?”

“Nope,” he answered. “This is pretty normal for a Wednesday afternoon, especially since the iPhone 3G S release.”

So, to set the scene: The retail stores of Apple Inc., a company not even in the mobile phone business two short years ago, are jammed with people craving iPhones and other networked computing devices. And competing choices from a dozen other major mobile device companies are proliferating and leapfrogging each other technologically so fast as to give consumers headaches.

But amid this avalanche of innovative alternatives, we hear today that:

The Department of Justice has begun looking into whether large U.S. telecommunications companies such as AT&T Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc. are abusing the market power they have amassed in recent years . . . .

. . . The review is expected to cover all areas from land-line voice and broadband service to wireless.

One area that might be explored is whether big wireless carriers are hurting smaller rivals by locking up popular phones through exclusive agreements with handset makers. Lawmakers and regulators have raised questions about deals such as AT&T’s exclusive right to provide service for Apple Inc.’s iPhone in the U.S. . . .

The department also may review whether telecom carriers are unduly restricting the types of services other companies can offer on their networks . . . .

On what planet are these Justice Department lawyers living?

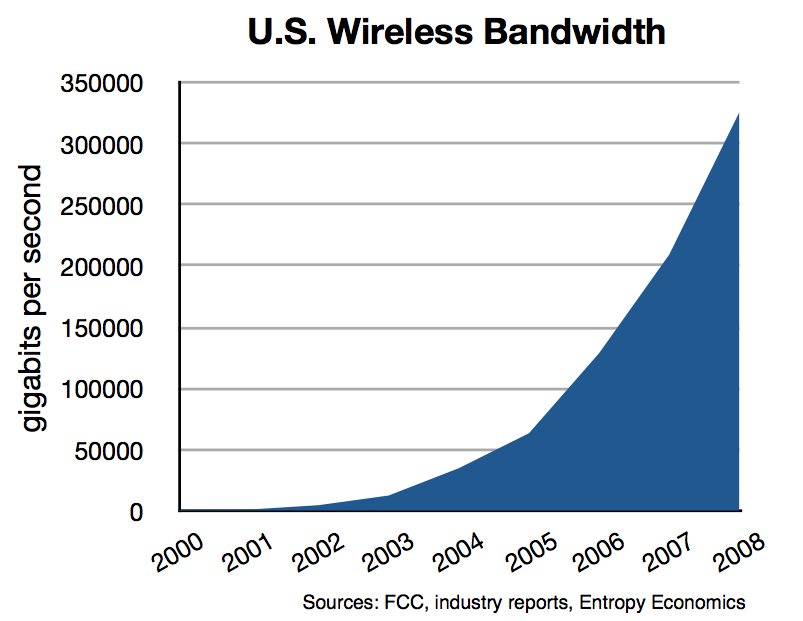

Most certainly not the planet where consumer wireless bandwidth rocketed by a factor of 542 (or 54,200%) over the last eight years. The chart below, taken from our new research, shows that by 2008, U.S. consumer wireless bandwidth — a good proxy for the power of the average citizen to communicate using mobile devices — grew to 325 terabits per second from just 600 gigabits per second in 2000. This 500-fold bandwidth expansion enabled true mobile computing, changed industries and cultures, and connected billions across the globe. Perhaps the biggest winners in this wireless boom were low-income Americans, and their counterparts worldwide, who gained access to the Internet’s riches for the first time.

Meanwhile, Sen. Herb Kohl of Wisconsin is egging on Justice and the FCC with a long letter full of complaints right out of the 1950s. He warns of consolidation and stagnation in the dynamic, splintering communications sector; of dangerous exclusive handset deals even as mobile computers are perhaps the world’s leading example of innovative diversity; and of rising prices as communications costs plummet.

Kohl cautioned in particular that text message prices are rising and could severely hurt wireless consumers. But this complaint does not square with the numbers: the top two U.S. mobile phone carriers now transmit more than 200 billion text messages per calendar quarter.

It’s clear: consumers love paid text messaging despite similar applications like email, Skype calling, and instant messaging (IM, or chat) that are mostly free. A couple weeks ago I was asking a family babysitter about the latest teenage trends in text messaging and mobile devices, and I noted that I’d just seen highlights on SportsCenter of the National Texting Championship. Yes, you heard right. A 15 year old girl from Iowa, who had only been texting for eight months, won the speed texting contest and a prize of $50,000. I told the babysitter that ESPN reported this young Iowan used a crazy sounding 14,000 texts per month. “Wow, that’s a lot,” the babysitter said. “I only do 8,000 a month.”

I laughed. Only eight thousand.

In any case, Sen. Kohl’s complaint of a supposed rise in per text message pricing from $.10 to $.20 is mostly irrelevant. Few people pay these per text prices. A quick scan of the latest plans of one carrier, AT&T, shows three offerings: 200 texts for $5.00; 1500 texts for $15.00; or unlimited texts for $20. These plans correspond to per text prices, respectively, of 2.5 cents, 1 cent, and, in the case of our 8,000 text teen, just .25 cents. Not anywhere close to 20 cents.

The criticism of exclusive handset deals — like the one between AT&T and Apple’s iPhone or Sprint and Palm’s new Pre — is bizarre. Apple wasn’t even in the mobile business two years ago. And after its Treo success several years ago, Palm, originally a maker of PDAs (remember those?), had fallen far behind. Remember, too, that RIM’s popular BlackBerry devices were, until recently, just email machines. Then there is Amazon, who created a whole new business and publishing model with its wireless Kindle book- and Web-reader that runs on the Sprint mobile network. These four companies made cooperative deals with service providers to help them launch risky products into an intensely competitive market with longtime global standouts like Nokia, Motorola, Samsung, LG, Sanyo, SonyEricsson, and others.

As The Wall Street Journal noted today:

More than 30 devices have been introduced to compete with the iPhone since its debut in 2007. The fact that one carrier has an exclusive has forced other companies to find partners and innovate. In response, the price of the iPhone has steadily fallen. The earliest iPhones cost more than $500; last month, Apple introduced a $99 model.

If this is a market malfunction, let’s have more of them. Isn’t Washington busy enough re-ordering the rest of the economy?

These new devices, with their high-resolution screens, fast processors, and substantial 3G mobile and Wi-Fi connections to the cloud have launched a new era in Web computing. The iPhone now boasts more than 50,000 applications, mostly written by third-party developers and downloadable in seconds. Far from closing off consumer choice, the mobile phone business has never been remotely as open, modular, and dynamic.

There is no reason why 260 million U.S. mobile customers should be blocked from this onslaught of innovation in a futile attempt to protect a few small wireless service providers who might not — at this very moment — have access to every new device in the world, but who will no doubt tomorrow be offering a range of similar devices that all far eclipse the most powerful and popular device from just a year or two ago.

— Bret Swanson

Quote of the Day

“There’s also no denying that these distribution deals have benefited consumers. More than 30 devices have been introduced to compete with the iPhone since its debut in 2007. The fact that one carrier has an exclusive has forced other companies to find partners and innovate. In response, the price of the iPhone has steadily fallen. The earliest iPhones cost more than $500; last month, Apple introduced a $99 model.

“If this is a market malfunction, let’s have more of them. Isn’t Washington busy enough re-ordering the rest of the economy?”

— The Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2009

Altman’s treatment: Bleeding the patient

Roger Altman sees many of the same slow-growth problems that David Malpass warned against . . .

federal deficits may average a stunning $1 trillion annually over the next 10 years. This worsened outlook is stirring unease on Main Street and beginning to reorder priorities for President Barack Obama . . . .

The burst of spending in recent years and the growing likelihood of a weak economic recovery. The latter would mean considerably lower federal revenues, the compiling of more interest on our growing debt, and thus higher deficits. . . . the latest data suggests that we’re on a much slower path. Probably along the lines of the most recent Goldman Sachs and International Monetary Fund forecasts, whose growth rates average about 2% for 2010-2011.

A speedy recovery is highly unlikely . . . .

. . . but unlike Malpass’s pro-growth strategy, Altman proposes to make matters worse:

we’ll have to raise taxes.

Today, the U.S. ranks next to last among the 28 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development nations in total federal revenue as a share of GDP. Our federal revenues represent 18% of national output, down from 20% just 10 years ago. That makes the mismatch between our spending and our revenue very large, producing the huge deficits we face.

We all know the recent and bitter history of tax struggles in Washington, let alone Mr. Obama’s pledge to exempt those earning less than $250,000 from higher income taxes. This suggests that, possibly next year, Congress will seriously consider a value-added tax (VAT). A bipartisan deficit reduction commission, structured like the one on Social Security headed by Alan Greenspan in 1982, may be necessary to create sufficient support for a VAT or other new taxes.

. . . it is no longer a matter of whether tax revenues must increase, but how.

Jackson’s traffic spike

Om Malik surveys the Net traffic spike after Michael Jackson’s death:

Around 6:30 p.m. EST, Akamai’s Net Usage Index for News spiked all the way to 4,247,971 global visitors per minute vs. normal traffic of 2,000,000, a 112 percent gain.

“New norm” warning

Tough stuff from the always-insightful David Malpass, who warns that slow growth from a lower economic base could yield an historic downgrade of the U.S. experiment:

With the crisis taking a deep toll on our economy, the expectation is for a “new norm” once recovery kicks in. It’s a dismal prospect: slower growth from a lower base, with higher unemployment and bigger government.

Rather than a healthy frugality, the new norm implies an outright decline in median living standards, a disaster for both prosperity and fairness. For President Obama such economic mediocrity spells extended deficits, a “jobless” recovery and, at best, a stiff reelection fight instead of the cakewalk that his perfect timing–inaugurated at the exact bottom of the crisis–deserves.

The U.S. decline isn’t inevitable. Game changers exist. The Fed could improve dollar policy to make the tens of trillions of dollars in new U.S. Treasury debt more salable. It should stop buying Treasurys to make it utterly clear that it will not monetize debt. Buying Treasurys is the monetary equivalent of government workers digging a hole, filling it back up and calling it GDP.

To underscore the new commitment to price stability and creditors the Fed has to stop using core inflation for its report card. It’s a loud signal to the world, proclaiming: “The Fed is not serious. Money should flow to Asia. Sell the dollar.”