Tomorrow, a host of Silicon Valley firms will visit Trump Tower for a meeting with the President-elect. Last week, AT&T and Time Warner visited Capitol Hill to testify about their proposed merger. These diverse companies build lots of things, from software to networks to original content, but they also have one thing in common. Increasingly they are all vying for bigger chunks of the video market, and in the process they are creating an entirely new media universe.

Too often when policymakers look at these companies, individually or in small sets, they see only what it right in front of them, rigidly defined and static, or even stereotypes of what these companies were a generation ago. But these companies — and the markets in which they play — are changing every day.

Several years ago, in a report called “Life After Television,” we noted that the YouTube and Netflix phenomena were only just the most obvious and earliest manifestations of the Web video revolution. We noted that, yes, the more abundant bandwidth of cable TV and then satellite had been improving the video market for years, but that even bigger changes were coming. This process, we said, would be intense, and messy, and often exhilarating.

Broadband and the Web have now super-charged all these phenomena. We enjoy far more choice and diversity, and the spectrum of quality is broader still. The producers, delivery channels, and business models for video are also multiplying (and in some cases recombining and overlapping in surprising ways). We are only in the middle of the beginning of what will be a decade-long process of sorting out the video content, creation, distribution, aggregation, user-interface, viewing, advertising, and subscription markets.

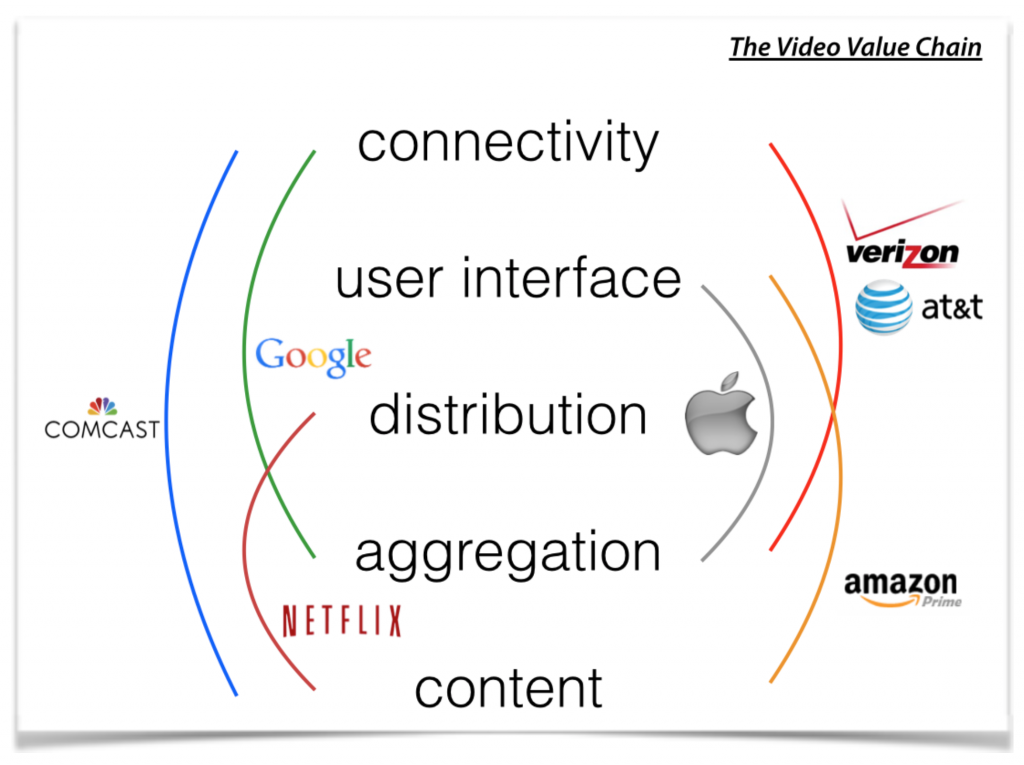

Here is the graphic we used to describe, in simplified form, the overlapping activities of firms competing in the video market, often approaching from very different angles and starting points.

Graphic describing simplified video value chain, circa 2014, in Life After Television.

The firms pictured are still at the center of the new media tussle. But others have joined the fray, and the battlefield is constantly shifting. Facebook, for example, was not even on our 2014 graphic, but in the subsequent two years it has become a giant player in the Web video (and thus advertising) market. At the time of our report, only Comcast covered the full spectrum, from connectivity to content. But in the meantime Verizon added content via its purchases of AOL and Yahoo, and AT&T is adding content with its Time Warner acquisition. Netflix and Amazon have only expanded as award-winning production houses of original content. Google and Apple, of course, continue to approach video with distinct business models — Google via advertising and the Web, Apple via a la carte and apps — but each remains a powerful player. And we are still only, perhaps, at the end of the beginning of this media reshuffling.

This new media world is emblematic of an even larger phenomenon of dynamic competition across the technology landscape. I described this even wider playing field in another report called “Digital Dynamism: Competition in the Internet Ecosystem,” which illustrated the multidimensionality of the market. This new market was characterized by intensive innovation, product differentiation, and cascades of competitive and complementary products and services.

The dynamism of the Internet ecosystem is its chief virtue. Infrastructure, services, and content are produced by an ever wider array of firms and platforms in overlapping and constantly shifting markets.

The simple, integrated telephone network, segregated entertainment networks, and early tiered Internet still exist, but have now been eclipsed by a far larger, more powerful phenomenon. A new, horizontal, hyperconnected ecosystem has emerged. It is characterized by large investments, rapid innovation, and extreme product differentiation.

There is both more competition, and more complementarity, than ever before. Which is why policymakers or pundits who are quick to shout “monopoly” in any of these contexts is almost surely wrong. Yes, some of these firms have large market shares in small portions of this overall digital world, but these share are often gained through real innovation, and even then they are often fleeting. These markets are way too fluid to assume anyone has a lock on any part of it, let alone a dominant position overall. So a merger of, say, AT&T and Time Warner, might to some look like “consolidation,” when in fact it potentially provides highly innovative and beneficial new competition in the online advertising business, where at the moment Google and Facebook are the biggest players.

It’s way too early to predict where all this will end up, let alone to dictate and end game.