On Sunday, Ross Douthat of the New York Times questioned the courage of Speaker Paul Ryan, asking why he hasn’t stood up more forcefully against Donald Trump. I, too, wish Ryan and other GOP leaders would (or could) explicitly denounce or otherwise frustrate the Trump candidacy. The complexity and delicacy of Ryan’s task, however, should not be underestimated. In today’s environment, might denunciations from the Speaker of the Establishment actually fuel Trump’s fire?

If I sympathize with Douthat’s frustration at GOP “paralysis,” however, I confess befuddlement at Douthat’s key takeaway: that the GOP should consider abandoning a growth-oriented agenda in favor of more Trump-like policy pandering.

One reasonable response to this kind of stark challenge, this incipient revolution, would be soul-searching and a course correction. Trump would not have gotten this far, would not have won so many votes — especially working class votes — if the Kempian vision had delivered fully on its promises, if mass immigration, free trade, deregulation and upper-bracket tax cuts had really been the prescription for all economic ills.

This is baffling. Douthat’s premise is that Ryan’s pro-growth agenda was enacted, and failed. Where has he been for the last 15 years?

Deregulation? The last two administrations, but especially the Obama administration, have built new mountains of regulation in finance (Sarbox, Dodd-Frank), energy (Clean Power Plan, ad infinitum), health care (Obamacare), education, the Internet (Title II), and a host of executive actions.

Tax cuts? The George W. Bush administration mildly cut dividend and capital gains rates the top individual rate, but Obama has mostly reversed those actions and added new taxes as well. The top tax rate is thus 15 points higher than the Reagan-“Kempian” 28% (more like 20% when accounting for state taxes), and much of the rest of the world has in the interim leapfrogged the U.S. in corporate and individual tax policy.

Trade? The Bush administration ran a weak dollar policy explicitly to help U.S. manufacturers and counter the China “threat,” just as Trump might have advised. But the effect was to inflate energy and home prices and contribute to the financial crisis.

Douthat is also worried about Ryan’s proposed entitlement stinginess. But the George W. Bush administration substantially expanded Medicare through the Part D dug benefit, and other safety net programs like food stamps have exploded.

The idea that the ambitious agenda of Ryan, who has been Speaker for a couple months, has not worked is just weird. We’ve been doing just the opposite for the last decade and a half, and the economic results show it.

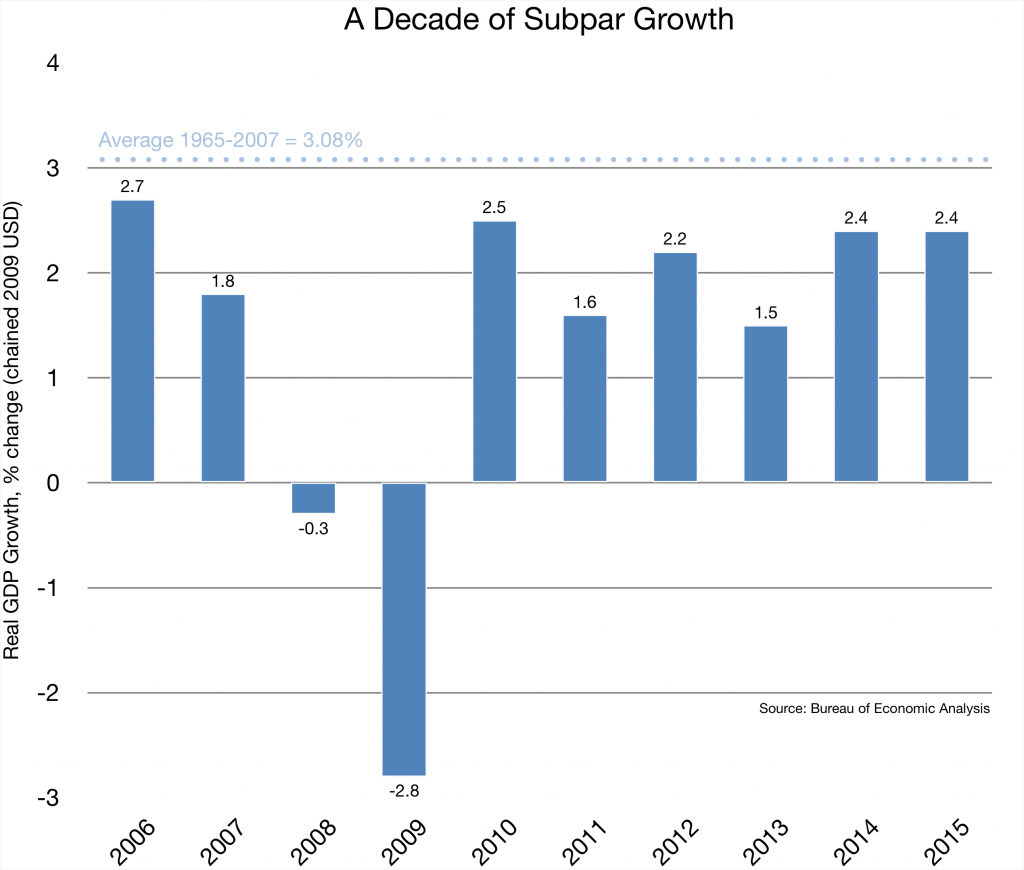

<

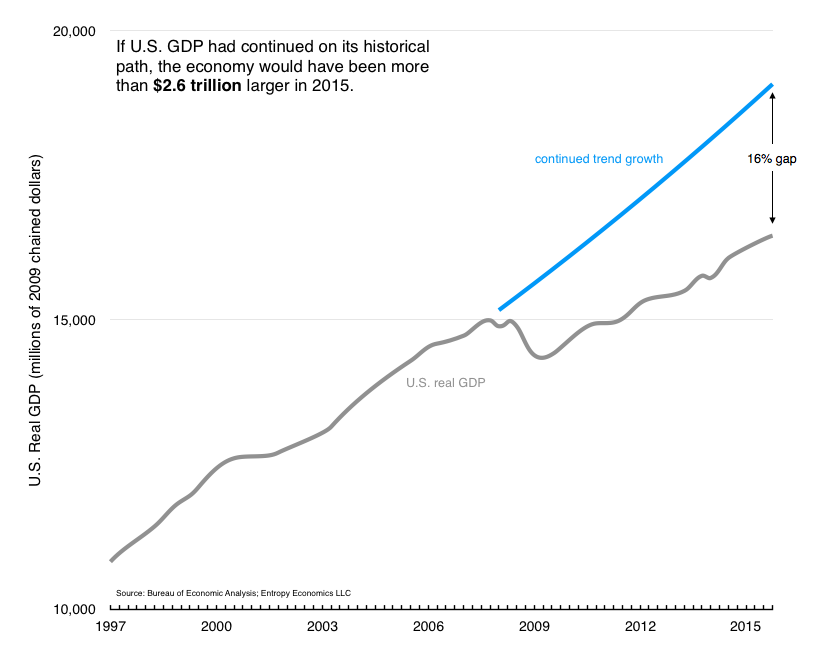

<

Douthat has written thoughtfully for many years on the plight of the middle class and, with his coauthor Reihan Salam, presciently urged the GOP to focus on the growing ranks of citizens, invisible to Washington, who now appear to be voting for Trump. For the last several years, conservatives have engaged in a polite debate over the best way to help. Douthat and a host of very smart and admirable policy thinkers have advocated something they call reform conservatism, earning the name Reformicons. The theoretical case, most powerfully explicated by Yuval Levin, emphasizes the importance of human capital – fertility, family, education – and the civic institutions needed to support these things. The cost of raising productive children is rising (I know, I’ve got four between the ages of 8 and 14), and the experiences of Japan, Italy, and other aging societies should be a warning. The resulting policy agenda, however, has proved less inspiring. The basic idea is to more narrowly focus various subsidies, entitlements, and tax benefits on the invisible low- and middle-income groups and explicitly renounce “tax cuts for the rich.”

The Reformicons like to needle growth advocates that they are nostalgic for Ronald Reagan and the 1980s, that we need to modernize our economic program. But I think they have it backwards. Reform conservatism appears to be mostly a rebranding of George W. Bush’s compassionate conservatism – big spending, more entitlements, a focus on targeted tax cuts and benefits, trade protectionism to help blue collar manufacturing, such as the weak dollar policy and Chinese steel tariffs, and efforts to improve human capital, such as No Child Left Behind. It was all well-intentioned, but not so successful. Especially for the Americans those programs sought to help.

I think the Reformicons should be commended for their focus on the middle class in “real America” and especially for their emphasis on human capital. But their attacks on a 21st century growth agenda these last few years may be endangering the very people for whom they are fighting. No doubt, the decline of cultural capital that Charles Murray warned of in Coming Apart is crucial and ever more apparent. But tax credits are unlikely to bring the type of cultural renewal that’s needed. And adopting Democratic tax policy and tax rhetoric isn’t going to win economically or politically. Another substantive problem is that as we build up means-tested credits and benefits for lower and middle income workers, we also impose high marginal tax rates on them due to phase outs. Economics isn’t everything. But the biggest drivers of well-being for moderate income Americans, including the opportunity to escape the cultural vortex and form robust civic connections, are still innovation, productivity, and economic growth.

“Sclerotic growth is the overriding issue of our time,” writes economist John Cochrane.

From 1950 to 2000 the US economy grew at an average rate of 3.5% per year. Since 2000, it has grown at half that rate, 1.7%. From the bottom of the great recession in 2009, usually a time of super-fast catch-up growth, it has only grown at two percent per year2. Two percent, or less, is starting to look like the new normal.

Small percentages hide a large reality. The average American is more than three times better off than his or her counterpart in 1950. Real GDP per person has risen from $16,000 in 1952 to over $50,000 today, both measured in 2009 dollars. Many pundits seem to remember the 1950s fondly, but $16,000 per person is a lot less than $50,000!

If the US economy had grown at 2% rather than 3.5% since 1950, income per person by 2000 would have been $23,000 not $50,000. That’s a huge difference. Nowhere in economic policy are we even talking about events that will double, or halve, the average American’s living standards in the next generation.

I’ve been shouting these ideas from the rooftops for the last five years (see The Growth Imperative, The Growth Agenda, and many more). Although I had no idea Donald Trump would run for office, let alone gain any following, I wrote a memo in 2014 warning of the social implications of an underperforming economy.

“The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like these,” the Nobel laureate economist Bob Lucas wrote in 1988, referring to the topic of economic growth, “are simply staggering: once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.” As Lucas explored what made some nations wealthy and others less so, he looked at a number of developing countries and reported the stark differences in growth rates and thus standards of living. Between 1960 and 1980, India, for example, grew 1.4 percent per year, while South Korea grew at an annual rate of 7.0 percent. At those rates, Lucas concluded, “Indian incomes will double every 50 years; Korean every 10. An Indian will, on average, be twice as well off as his grandfather; a Korean 32 times.”

Einstein referred to the same idea when he quipped — apocryphally, it turns out — that compound interest is the most powerful force in the universe. Whoever put those words in Einstein’s mouth was smart. The same idea is behind Moore’s law of microchips. Compound growth is transformative. It trumps all — maybe even a poisonous political environment.

The slow recovery from the Great Recession, on the other hand, is capping middle class incomes, driving Americans out of the workforce, piling up debt, and straining our social fabric. The politics of “inequality” and resentment are a natural outgrowth of such a malaise and can lead to a downward policy spiral if leaders do not offer an optimistic, compelling alternative.

The economy has not reached 3% growth, our historical average, in any of the last 10 years. Not because Paul Ryan’s growth agenda has failed but because in too many cases we did just the opposite.

There is of course no guarantee of 3% growth. It is merely an historical average. And yet there’s lots of evidence that our economy is operating well below potential. Yes, some structural factors like demographics are weighing on growth, but all the more reason to address the policy obstacles holding us back. Cochrane and John Taylor both think with better tax and regulatory policy we could grow at 4% for several years before returning to the long-run path around 3%. By all means, if we improve tax and regulatory policy to unleash the economy and we find pockets of Americans still struggling because of structural defects, let’s work to help those citizens in targeted ways. But it makes little sense to insist on, as the centerpiece of your program, and at the expense of a broader growth agenda, a host of complicated programs, credits, and subsidies seeking to ameliorate the very real effects of a stagnant economy: joblessness, underemployment, a stall in wages, and many resulting social problems.

Some of the Reformicons say its really regulation that’s holding the economy back, so we shouldn’t address taxes. Over-regulation is indeed a massive problem. But we don’t have to choose one or the other. We need to both downsize and modernize the Administrative State and reform the tax code.

And on language: The goal is tax reform — not tax cuts for this group or that. The objective is a new tax code — radically simpler, fairer, and pro-growth. Insisting that Republicans match the Democrats in a pledge against any tax reductions for anyone making $250,000 or more is self-defeating. It adopts the framing of big government advocates. And it makes tax reform impossible. Even corporate tax reform, which the Reformicons support, will reduce taxes for those making more than $250,000. So it appears to be little more than political capitulation that will do nothing to help the invisible Americans they so admirably would like to lift up. The Tax Foundation shows that tax reforms proposed in this campaign would deliver big benefits in jobs and wage growth while boosting GDP and delivering needed government revenues. Let’s not give up before we’ve begun.

_____

“Sclerotic growth is the overriding economic issue of our time.”

– John Cochrane

_____